Luker-

That is an interesting story about how you got into casting things.

My dad was the maintenance person for the family lumber mill, and when he retired, he needed something to do.

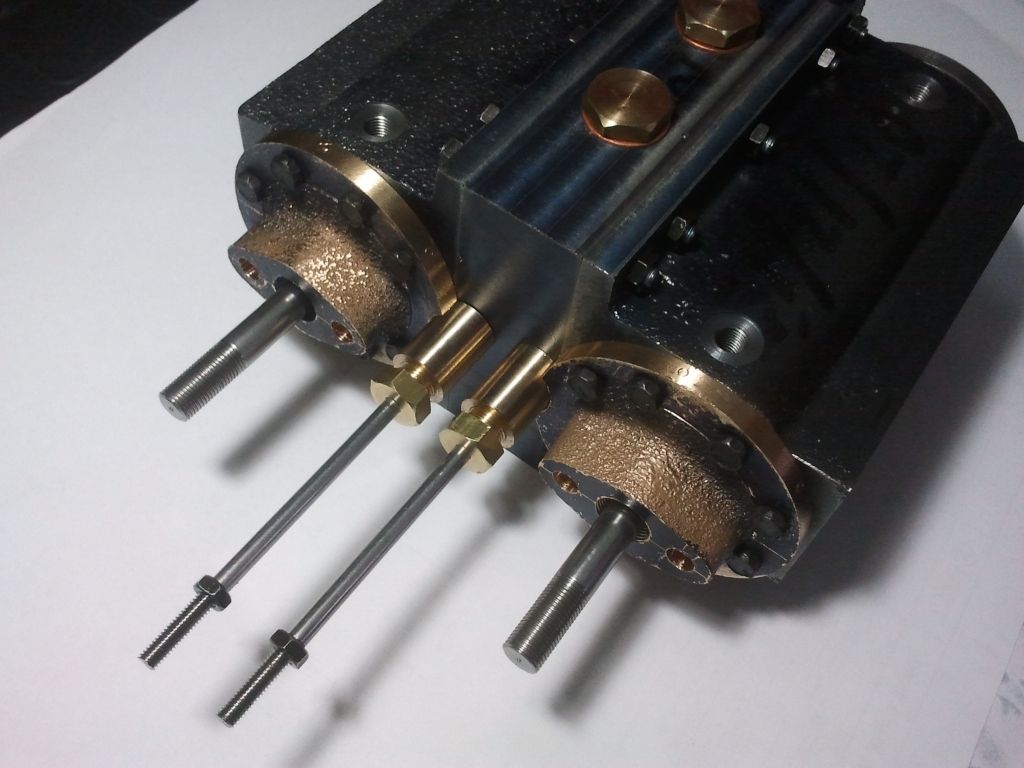

He set up a small home shop, and started making small steam engines.

He then started making model steam engines like the energizer bunny, ending up with some 38 engines before it was all over, all using bar stock construction.

I inherited his shop equipment, and so I decided to try my hand at model building.

I was shocked at how difficult and time consuming it was to hog engine parts out of solid blocks of gray iron, and inevitably, I would ruin the part just before I was able to complete the machining on it.

Dad's lathe and mill were not expensive, and so not up to the rigors of heavy machining.

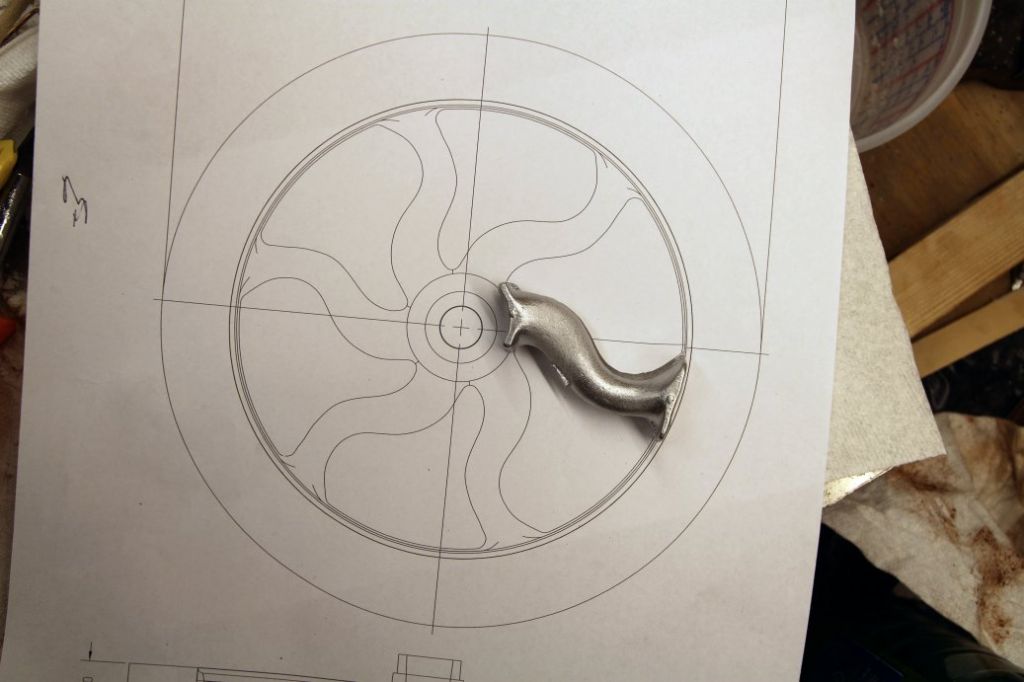

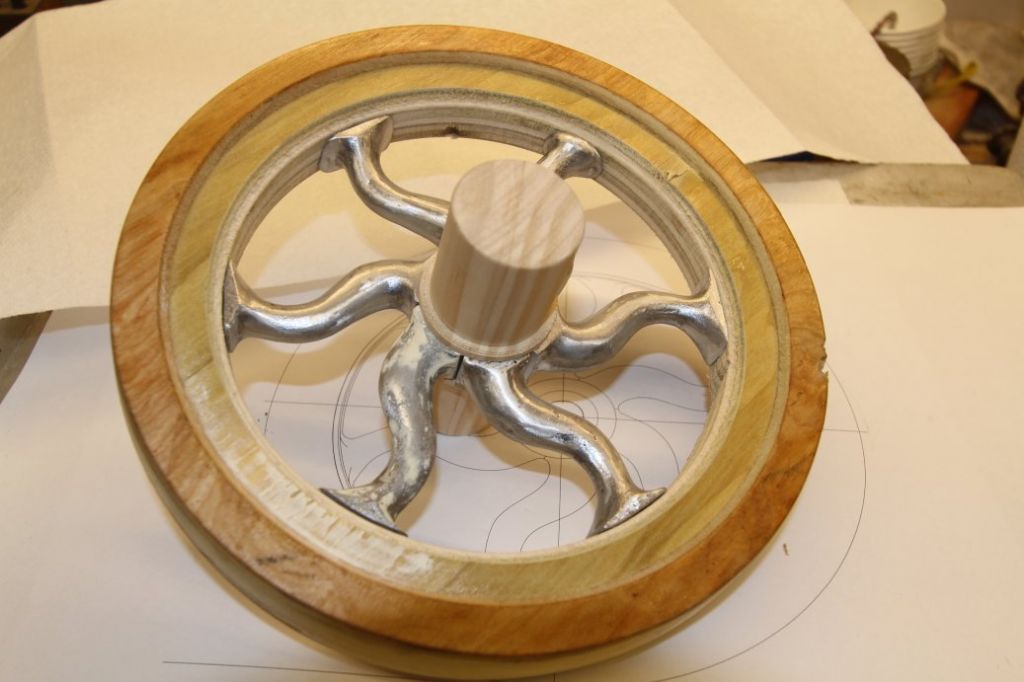

After many frustrating attempts at making various steam engine parts such as cylinders, flywheels with spokes, etc., and making some really doggy stuff, I exclaimed "There must be a better way to do this!".

I had a vague notion of the casting process, having toured the local International Harvester foundry when I was in school. I recalled hot metal, sand, and lots of steam/smoke coming out of the molds.

I set up a foundry, but was having a lot of problems with it.

The turning point for me was finding a local art-iron group that routinely cast aluminum (in Petrobond molds), and gray iron in resin-bound molds. These folks really brought me up to speed as far as mold materials, techniques, etc. The art-iron folks use cupolas to melt their iron, and I could not find any coke for fuel, so I started looking online for backyard furnace builds.

I studied about 10 different furnace/lid designs, and about 5 different burner designs.

The internet really helped me be able to find backyard casting material.

My first furnace was way too heavy, but my second furnace is a fraction of that mass, and my 2nd furnace works very well, especially with iron.

.

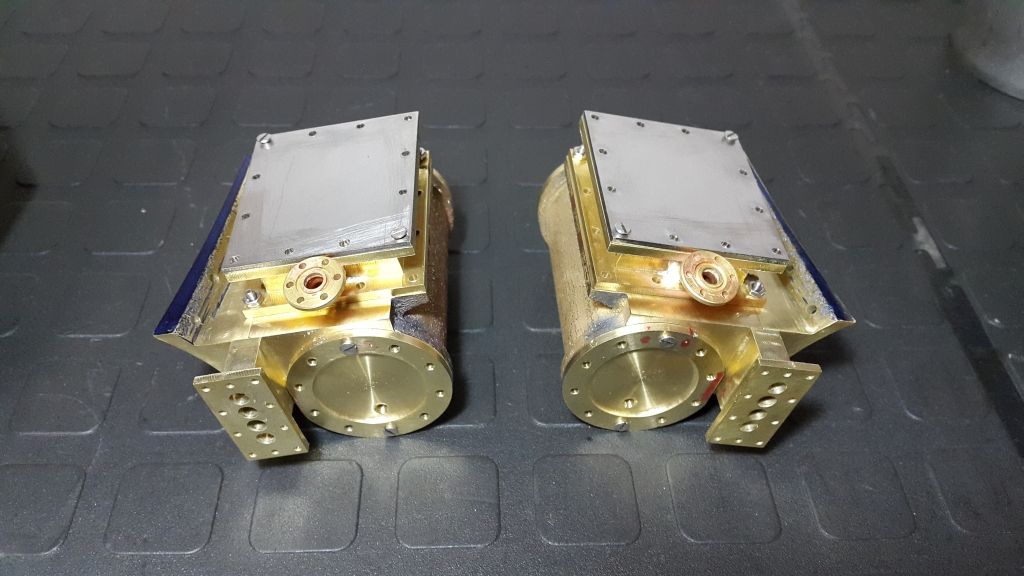

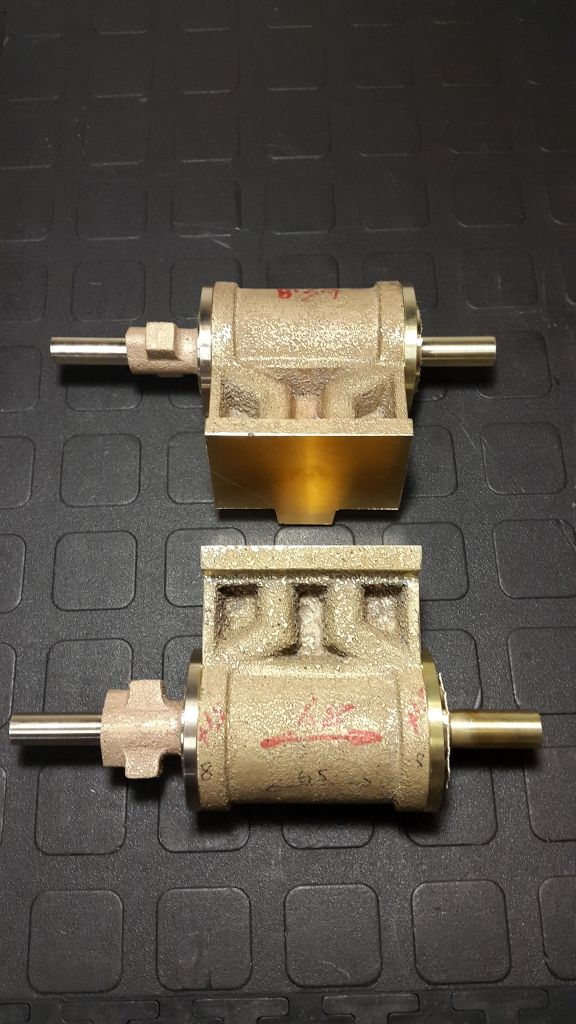

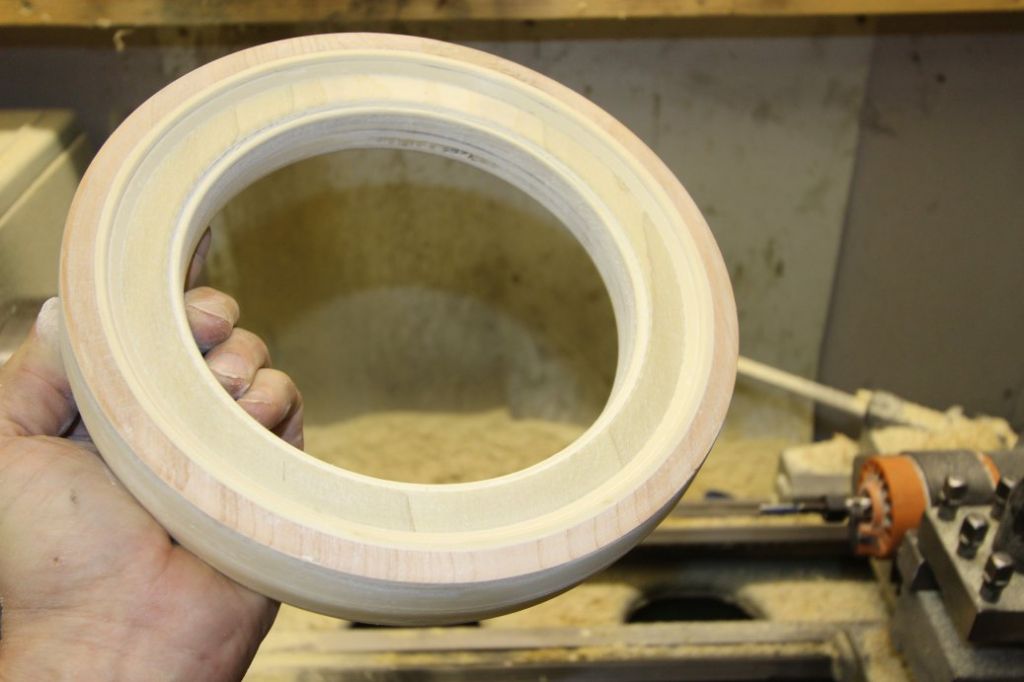

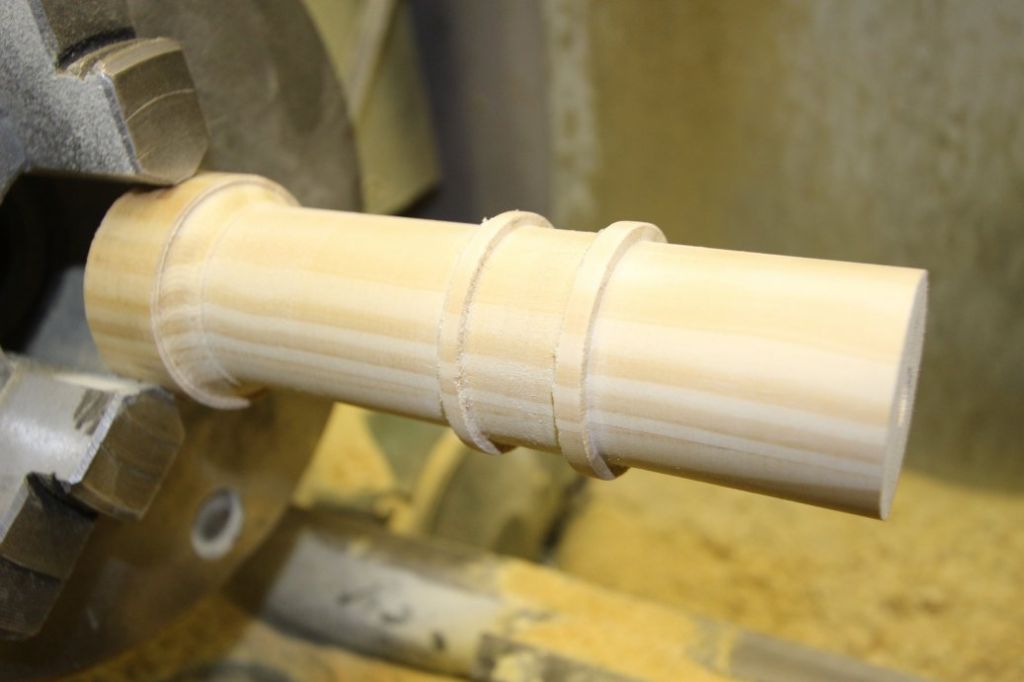

So basically what the foundry process allows me to do is "machine" my parts initially as patterns in wood.

Machining wood is infinitely easier than machining metal, and one can use fillers and such to make fillets.

Once a casting is made, the only machining I have do to is a light skim over the surfaces that require machining, and I am done. My relatively lightweight lathe and mill work well with the skimming process.

.

Another thing that has helped me a lot is learning 3D modeling. That has taken most or all of the guesswork out of engine design, and I can build an engine knowing it will work correctly, because I have already run it virtually in simulation using the 3D modeling program.

.

And with the advent of relatively inexpensive 3D printers, much of the tedium of hand making patterns has been removed, and my pattern and castings accuracy has gone way up.

I often see photos of old engines of all types, and I recall asking as a child "Can we buy one of those engines?", and the response whas always "No, they don't make them anymore".

I asked "Well can we make one?", and the response was "No, that is impossible".

There are very few phrases that bother me more than being told "That is impossible", especially given the fact that somehow making castings was possible for 1,000 (+) years.

The limiting factor as far as casting things is more about how much money you want to spend. You can set up an induction furnace and cast all your parts in stainless steel, if you have enough money, and enough time to learn the process.

.

Gray iron luckily melts at a low enough temperature that it can be cast with relative ease ("relative" being a relative term) .

A told a buddy of mine "You could just build a foundry and cast that engine part", and he said "Yes and I could teach a snake to tapdance, but first I have to get the shoes on him".

.

Edited By PatJ on 05/07/2022 13:56:36

noel shelley.