These ships were primarily cargo carriers – the largest could carry about 1000 tons – not warships, so were not very heavily armed, and would have avoided battles as far as possible. This one, based on contemporary practice, has only eight guns per side on the gun-deck and one each side on the main deck; and the guns are of fairly small calibre and range.

They still had to be able to defend themselves against pirates and in the 16C, when England and Spain were at war and both were trading across the Atlantic, attacks from English privateers who were basically a mixture of pirate and mercenary. The displays on board explained they normally worked in convoys of up to about thirty ships. That would have given some measure of mutual protection, but by the time they'd reached the far side of the ocean I imagine they would have been quite widely scattered and it would have been difficult for them to come to each other's aid.

It would still have been hell on the gun-deck when in action though. The usual tactic was to shoot broadsides as the only effective way to inflict much damage on the enemy in one shoot. The Andalucia does not display how they would have fought but on all ships armed like this, the muzzle-loading guns would have been drawn well inboard for loading, then run out to put the muzzles clear of the ship's side. Even so the gun-deck would have been extremely noisy spaces, soon filled with acrid smoke. Dangerous too, not only from the other ship trying to kill you, but with handling heavy wheeled gun-carriages by block and tackle in a confined compartment on a rolling ship.

.

Certainly all hand-tools. I am not sure if there is a distinction between Shipwright and Carpenter, the former being more the designer than maker of the components. They would have had drawings of some sort, if only showing the overall shapes and sizes and relying on experience for the details. I assume too, plenty of jigs and templates.

These skills had parallels elsewhere: the Mediaeval builders of the great cathedrals were supervised by the Master Mason, essentially the architect. As with ship-building, it involved a lot of repetition work; and structures like the roof trusses were typically made to jigs on the ground, dismantled and the marked parts hoisted up to be re-assembled.

The ship-wright's equivalents included the Moulding Loft – a large open room in which to lay out the shapes of the big components like the ribs.

The Ship's Carpenter would have been an important member of the crew, but I don't know if of some form of lower-officer rank on these Spanish cargo-ships.

.

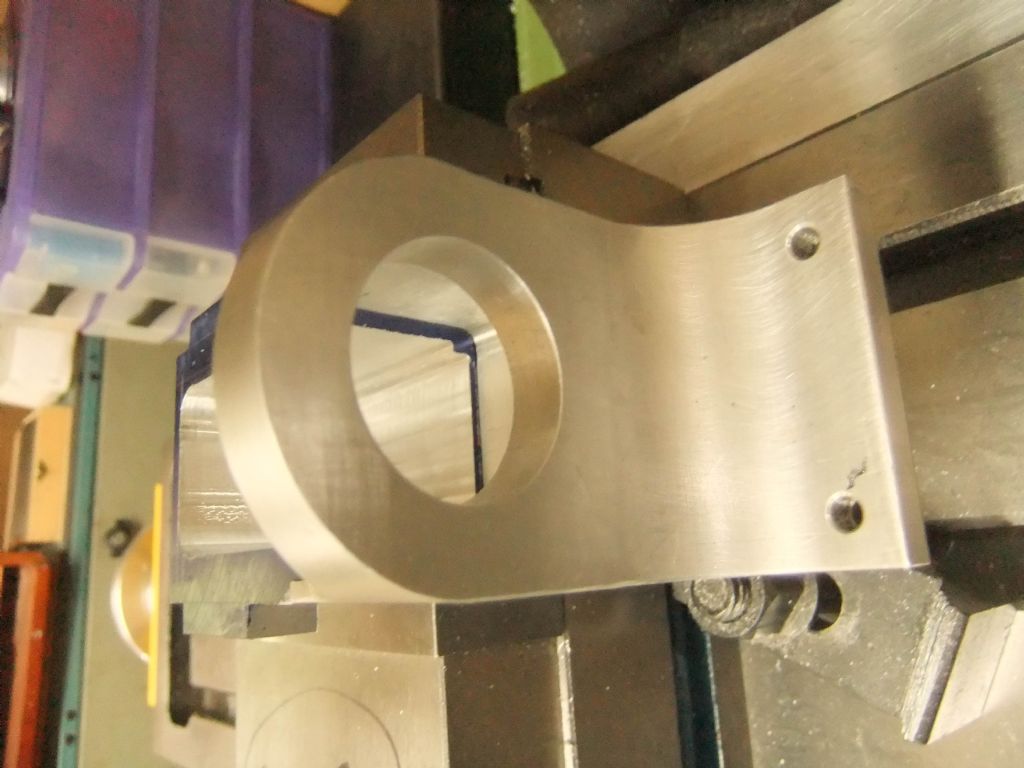

That massive block in the last photo is one of those at the base of the main-mast. The leather caps presumably protect the ropes and the edges of the wood from each other. Making so many blocks with sheaves that have to match each other and fit the ropes properly suggest to me that the equipment available 400 years ago was more sophisticated than we might think, even if driven by man-power. Turning was already an ancient skill, but a sailing-ship's rigging includes many parts that must be repeated many times over. Some places might have been able to use water-powered machinery.

What we know of Mediaeval to 18C manufacturing is somewhat sketchy, relying on surviving art rather than text-books of which few seem to have been written. Even so we can glean clues.

For example, I have seen one wood-cut suggesting guns such as the replicated-dummy ones on Andalucia were bored using a cutting-tool on the end of a long rod, possibly a screw, supported by trestles in front of the barrel. The tool was rotated by hand, so even one small weapon in bronze (as early ones were) probably took all day. The engraving did not reveal how the tool was guided but I would think by a collar acting like the lands on a twist-drill. These guns were all smooth-bores, of course.

Another example, going back to the architectural parallels… How did they manage without spirit-levels? I've seen one Mediaeval wood-cut shows a mason using a large square with a plumb-line suspended down the vertical side.

Matt T.