Taking a step back to some of Nicholas's posts suggests to me this one needs to go right back to first principles.

This is the machine, and Nicholas comments the seller dropped and damaged it:

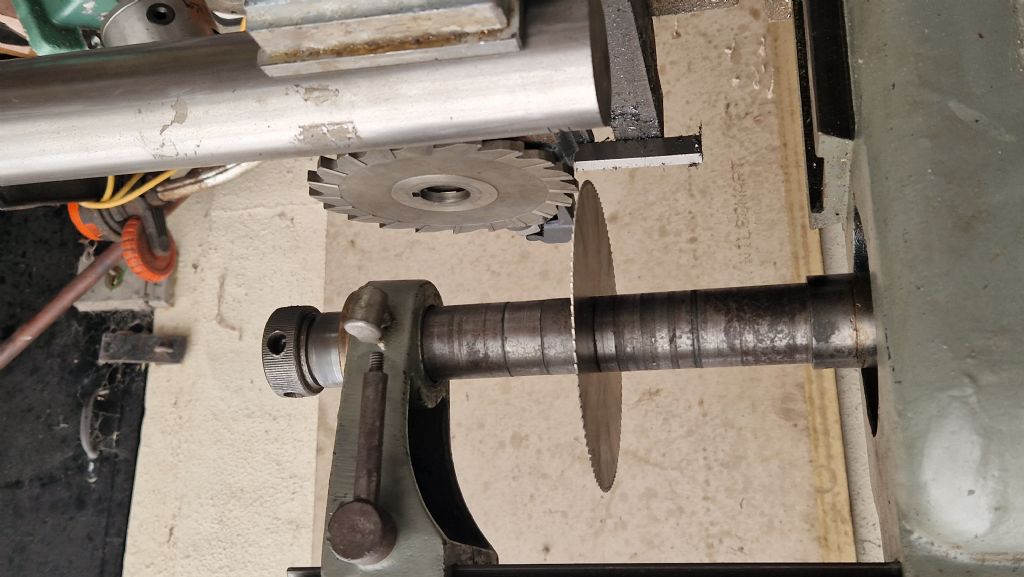

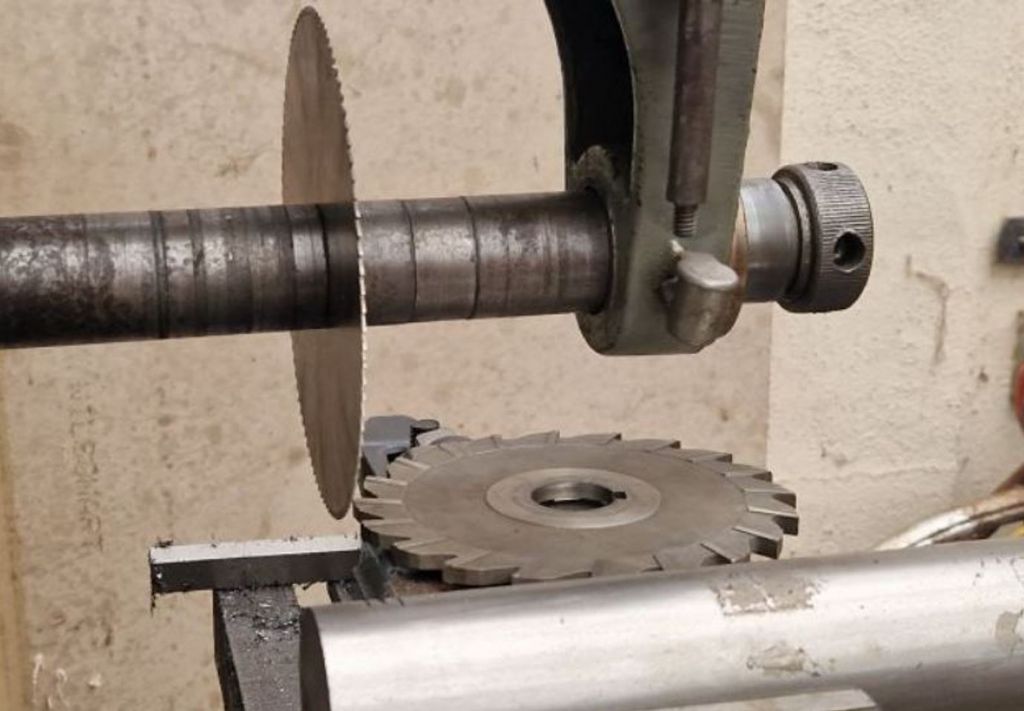

Note the sheered off hand-wheel, but also this:

Plus a question about gears and worms in relation to a need to replace a lead-screw.

So, a second-hand mill in unknown condition, that was significantly damaged before delivery, that's been renovated and is now being tested by a beginner, possibly using cutters and saws that may not be in tip-top condition either!

The picture shows a medium sized single-phase motor, so the machine isn't a powerful monster. However, the report of sparks (at the cutter I hope) suggests the motor and drive to the spindle are OK.

It's hard to debug a machine you have no feel for in normal operation. Therefore I suggest taking it step by step, assuming nothing, and gradually eliminating problems.

First step I suggest is a thorough mechanical check of the knee and table; these should move smoothly in one plane when the hand-wheels are operated, but otherwise be rigidly tight. Any movement in the mill's structure, dovetails, gibs or work-holding will cause chatter and dig-ins. Might be due to wear, but given the history it wouldn't be surprising to find damage or re-assembly errors, for example it's easy to put gibs in wrongly

Second step, make sure the material is cooperative. Many metals don't machine well, for which reason I recommend buying metal specified as free-cutting rather expecting my machines to munch through random scrap without bother. Although EN1a-Pb machines three times better than EN3, EN3 should be OK for testing the mill. But is it definitely EN3? If there's any doubt, change it.

Third step, make sure the speed, depth of cut and feed-rate are all a reasonable match to the cutter diameter and type. Lots of good advice already given. Usually I set RPM, then go for a reasonable depth of cut (depends on motor power and machine rigidity), and adjust feed-rate so the machine sounds as if it's working, but not being pushed. Two common beginner extremes are too-gentle pussy-footing, which causes word-hardening and rapid tool blunting, and grossly excessive expectations, where a bad-tempered gorilla expects a poor little machine to take massive cuts. Off the two the second is worse because it can damage the machine, worse if the heavy handedness extends to repairing the machine is well.

Fourth, make sure the cutter is in good condition, and spinning in the right direction (not in reverse!) Again, if there's any doubt, buy a new one!

Fifth, make sure the operator knows what he's doing. In my workshop more problems are caused by me than all other causes put together. I have to compensate for being clumsy and impatient as well as half-trained. Although confidence is important, it's no substitute for knowledge and experience. I'm self-taught, which took a lot of effort and has left all sorts of odd gaps in my skill-set. I've made some painful and expensive mistakes; the best way I've found to minimise them is to approach learning new tricks with caution. I read-up, search the forum, ask for advice and experiment first; I try hard to eliminate problems before jumping in at the deep end. As they say in the Army "Proper Planning and Preparation Prevents Piss-poor Performance".

Sixth, two or more faults present at the same time make debugging much harder. Don't jump too quickly to conclusions, rushing in and fixing the wrong things never works out well! Especially if they weren't broke in the first place. You can guess how I know!

Dave

not done it yet.