With the arrival of some additional material the build can now follow a more logical direction starting with the base.

As I said in the introduction the one supplied by Stuarts is little more than a rectangle with rounded corners and a bit of draft angle which only needs flattening on the bottom, skim cut off the top and a few holes added which does not give you much workshop time for your money as it should not take more than an hour to do.

I opted for aluminium as it's easy to cut and no more expensive than bright steel flat. I've not noticed any problems with my other models that use aluminium right from the early ones I made 30+ years ago like the Minnie which has several aluminium castings through to others with aluminium castings and the ones I have fabricated using the material. Even Stuarts have used it to cast the fluted column of the Williamson.

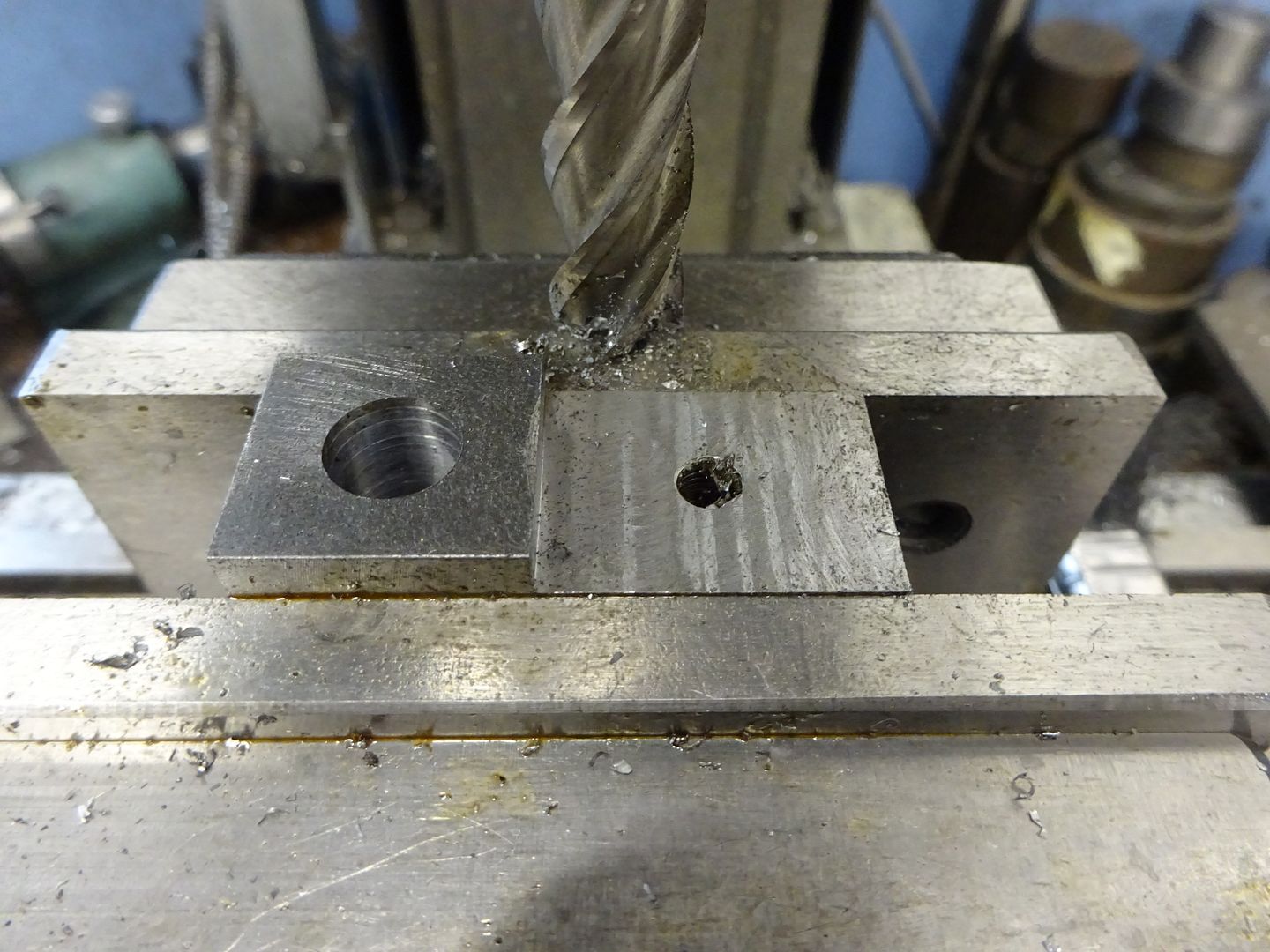

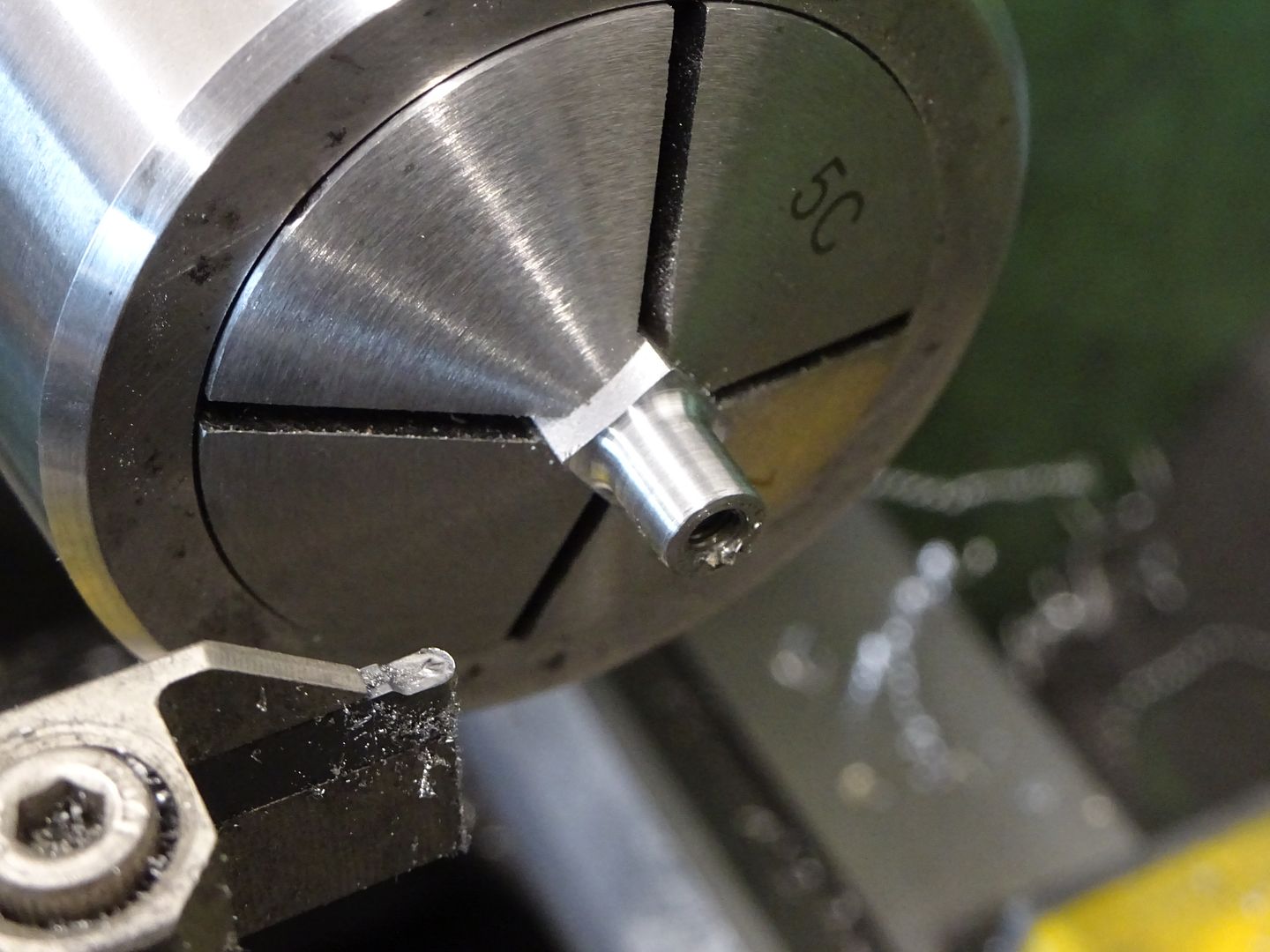

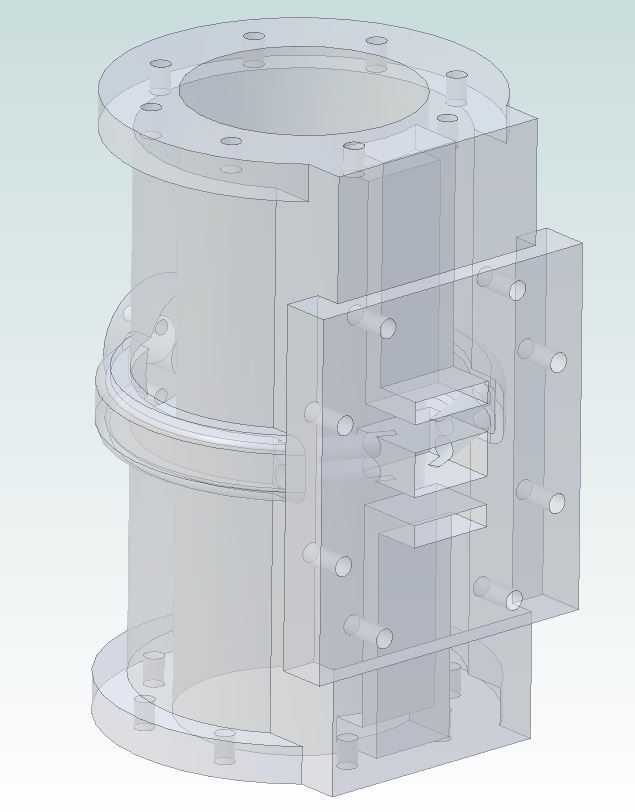

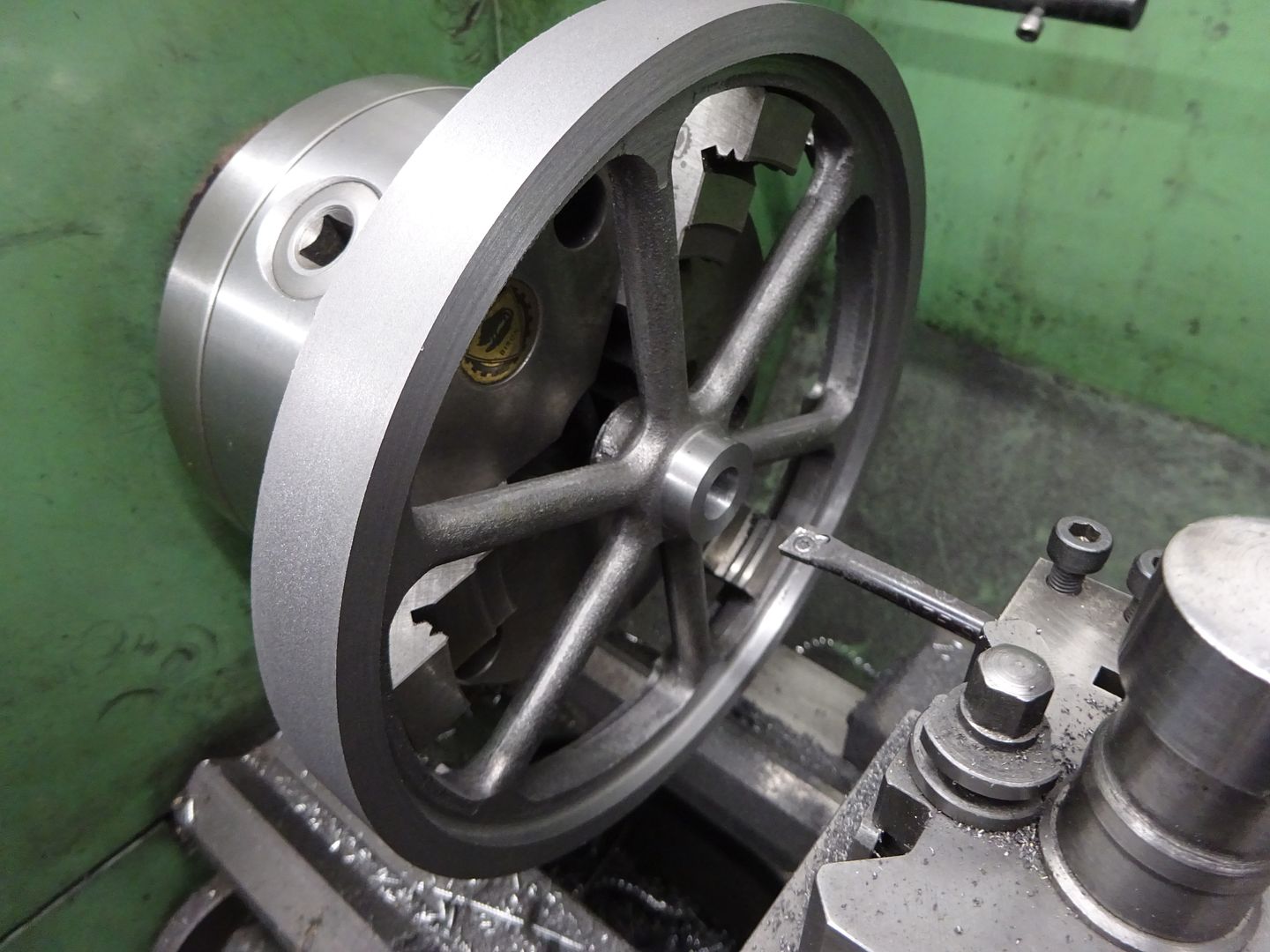

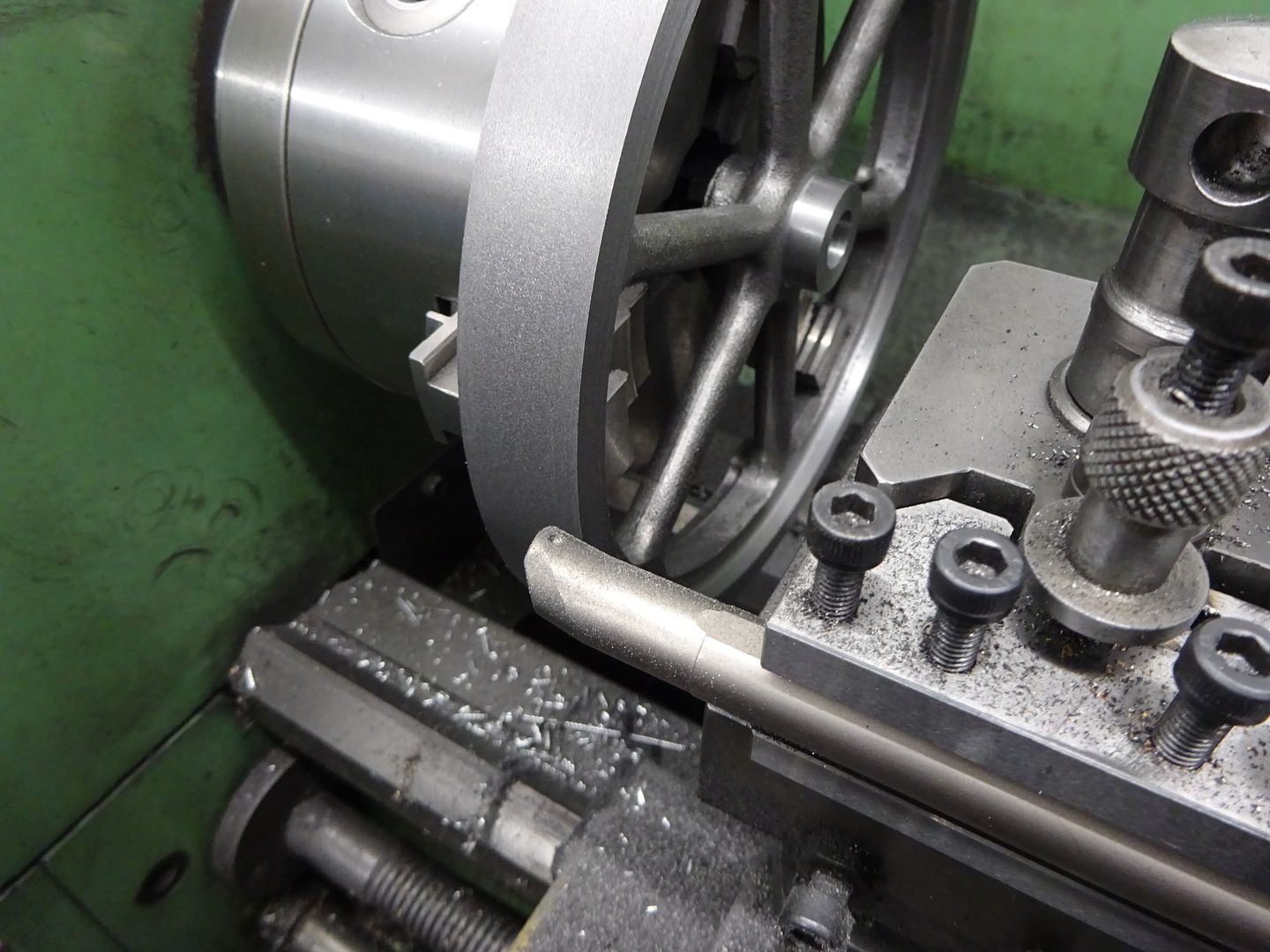

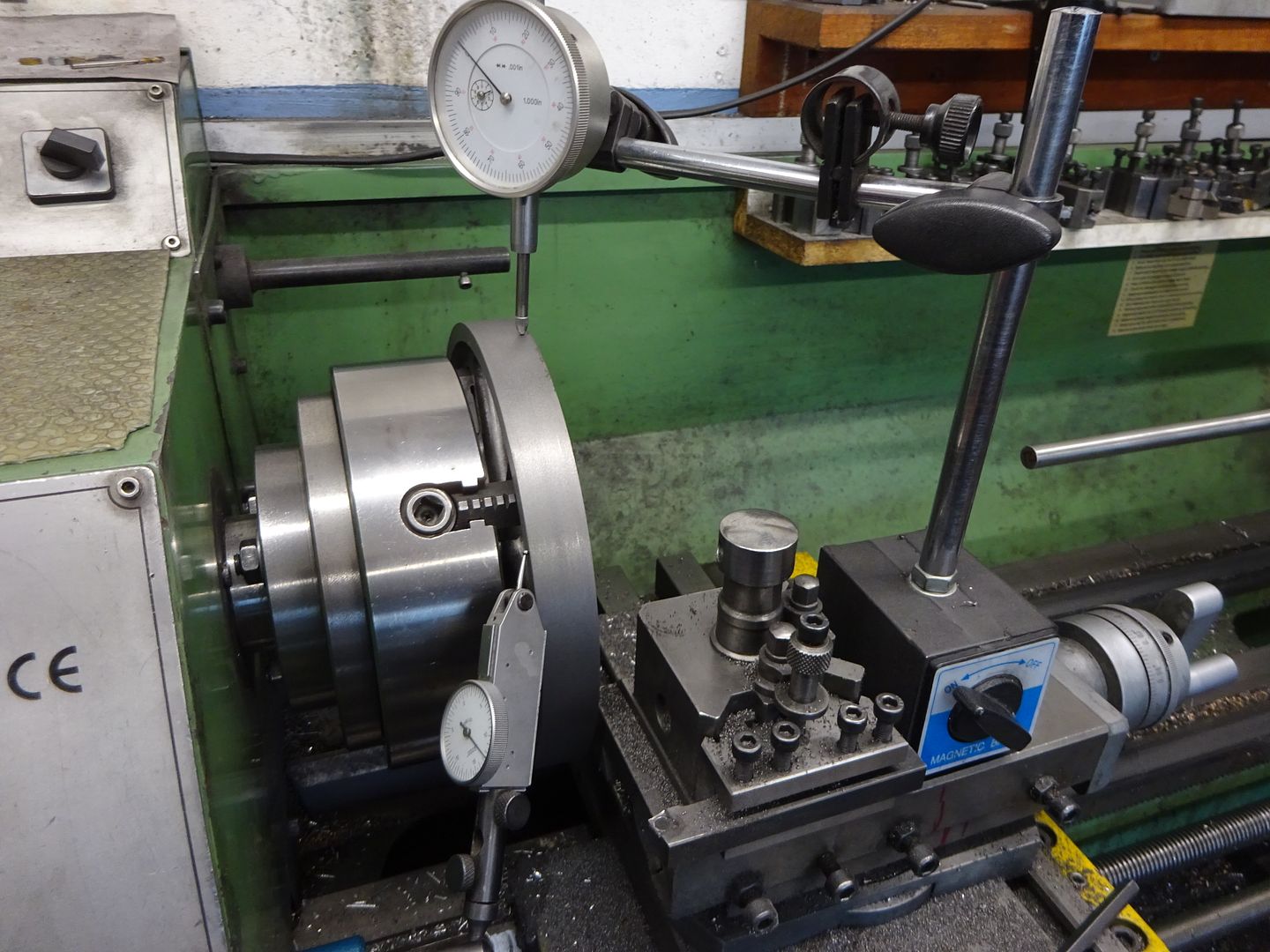

So starting with a piece of 12mm material it was sawn slightly oversize and clamped to the mill table on some packing so that three sides could be milled square to each other. I then drilled four hole 5mm which were later countersunk on the underside for M5 CSK socket screws. These holes were also counterbored from above by plunging with an 8mm 3-flute cutter to form sockets that spigots on the column bases will fit tightly into so they locate accurately. I also drilled and tapped M4 for the studs that will hold the cylinder cover in place and at the same time added a small hole to use as a datum at the ctr of the cylinder position that could be used to locate the base on the rotary table if using that to mill the half round.

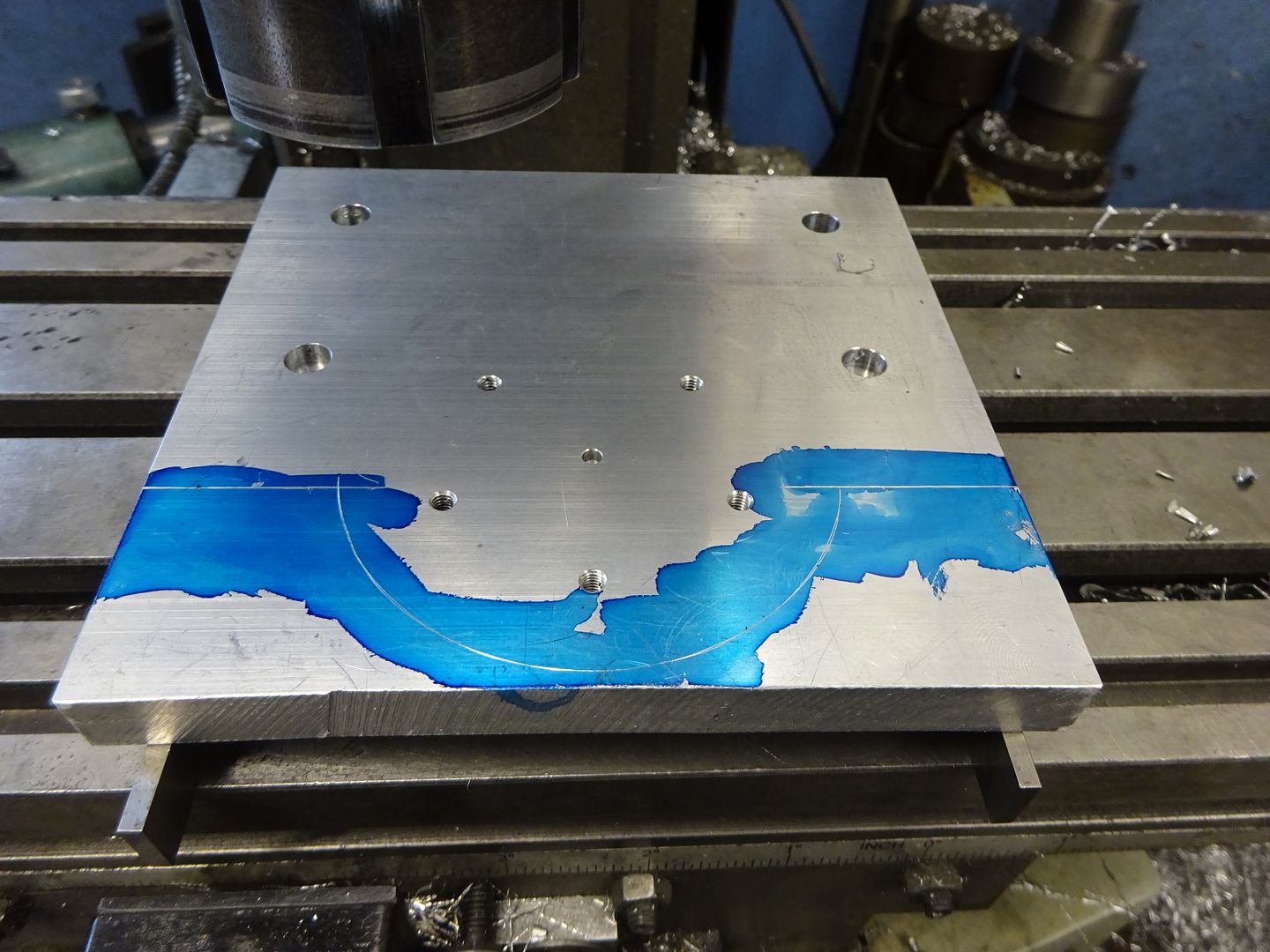

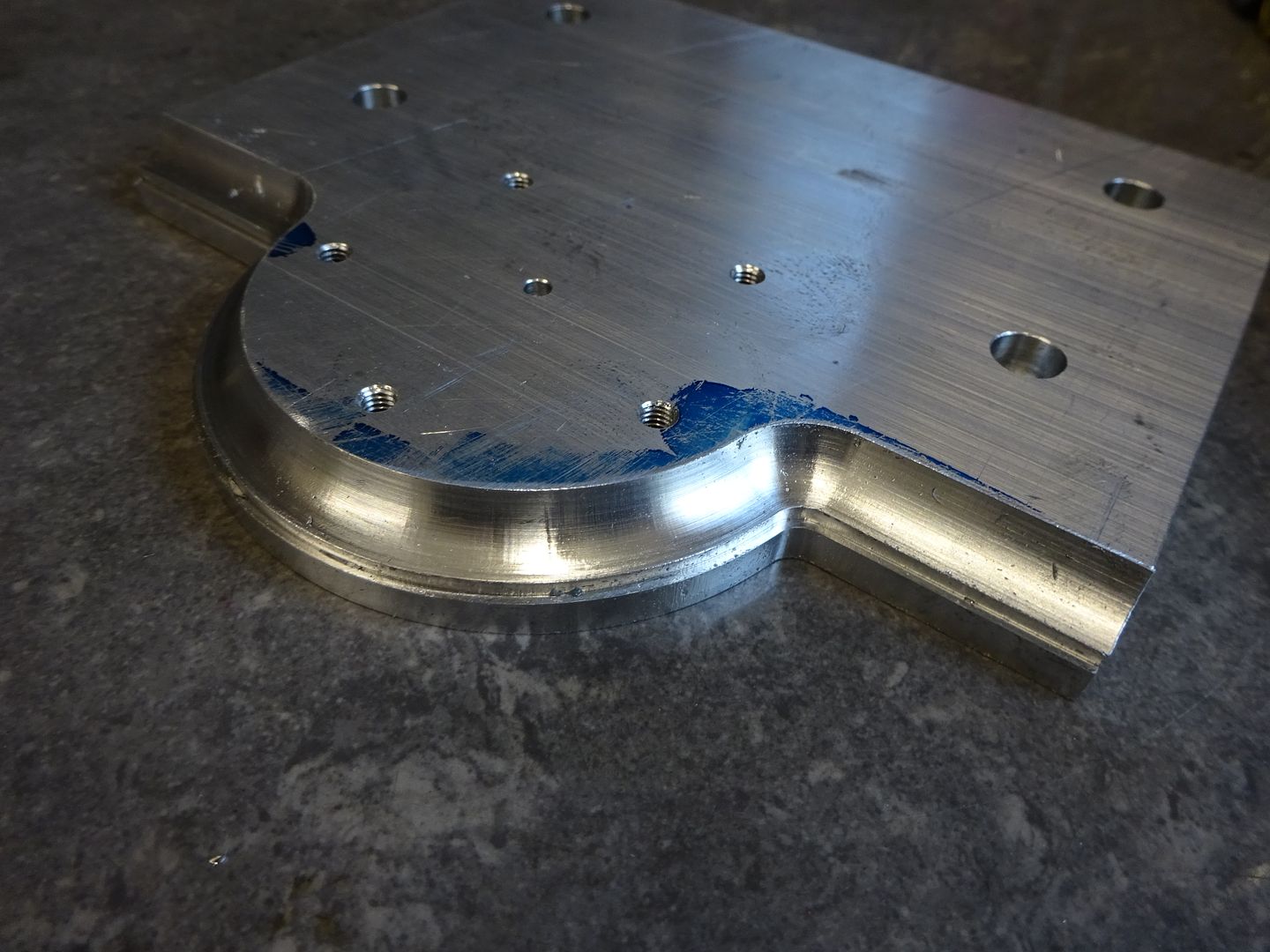

The two areas of waste were hacksawn off and put aside as they can be used for other parts later on then the front face with it's half round was milled to size and the decorative moulding added firstly by cutting a rebate 10mm deep and then using a 12mm ball nose cutter to do the concave detail.

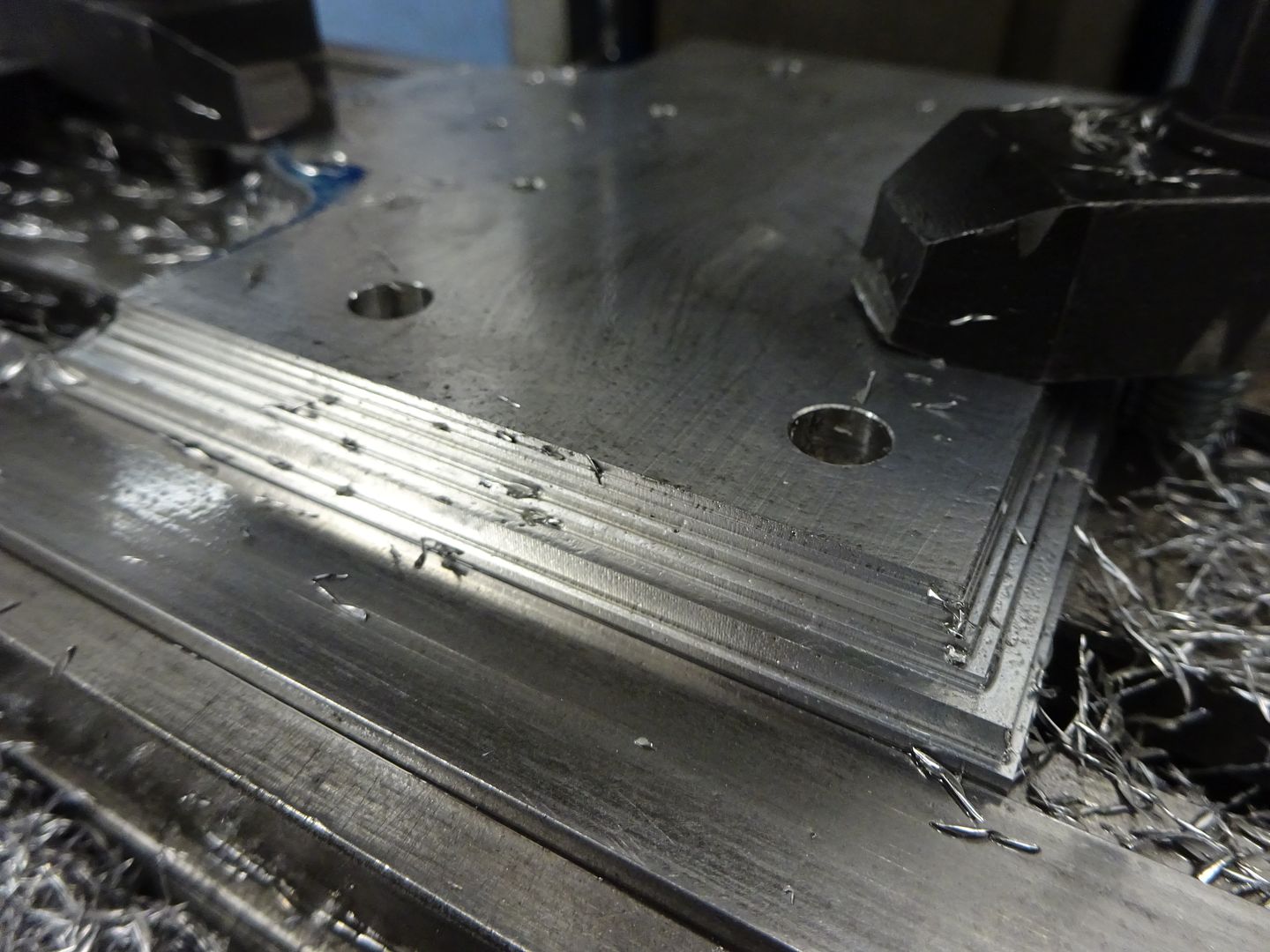

The straight sides were next, to make it easier I clamped a straight edge to the mill table and clocked it in so it was then an easy job to locate each side against this and machine at the same settings. First doing the rebate and removing some of the waste with the same straight 10mm cutter.

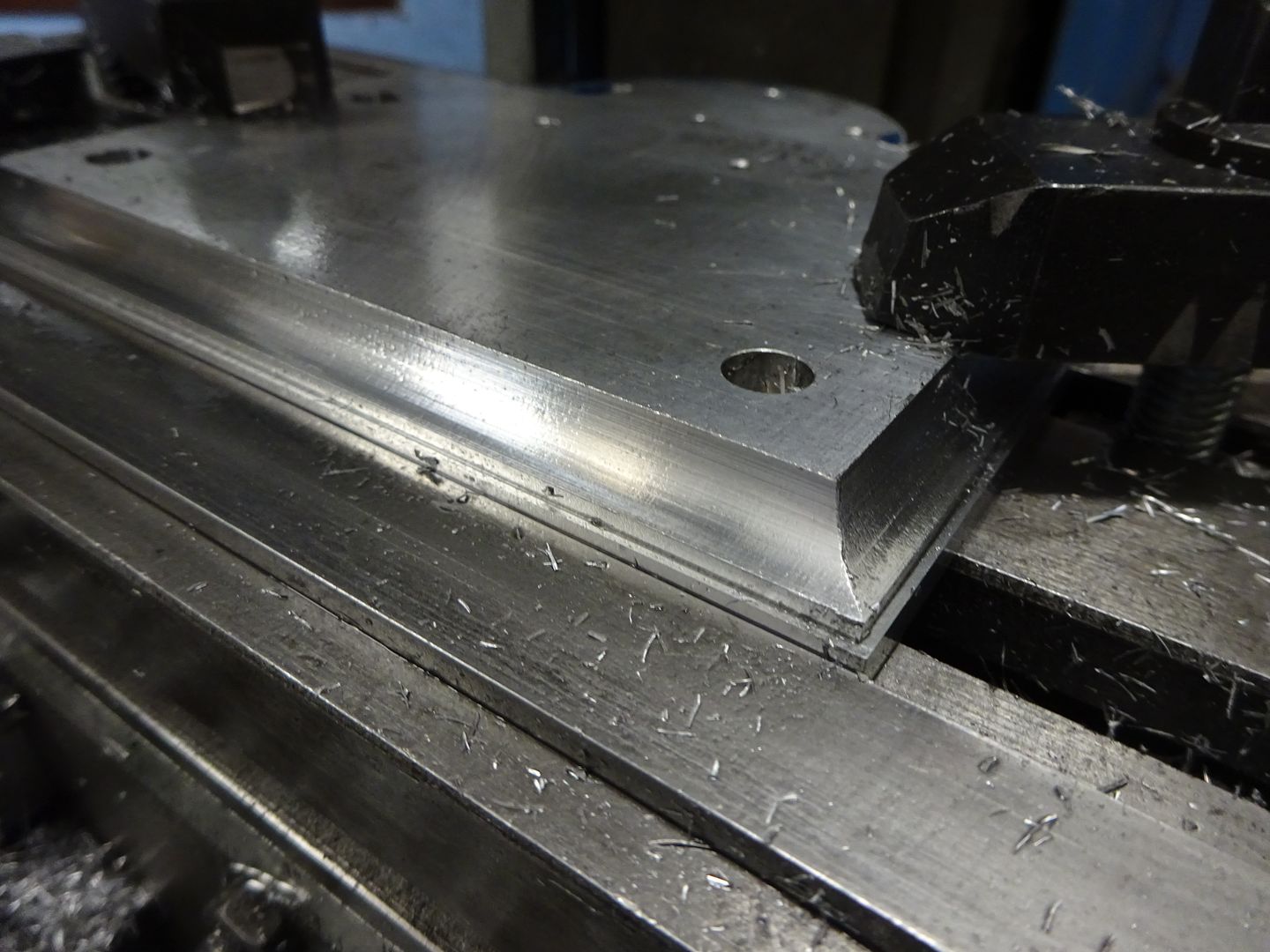

Then the concave with the 12mm ball ended one

You can always judge if you have had a productive session in the workshop by the size of the pile of swarf produced.

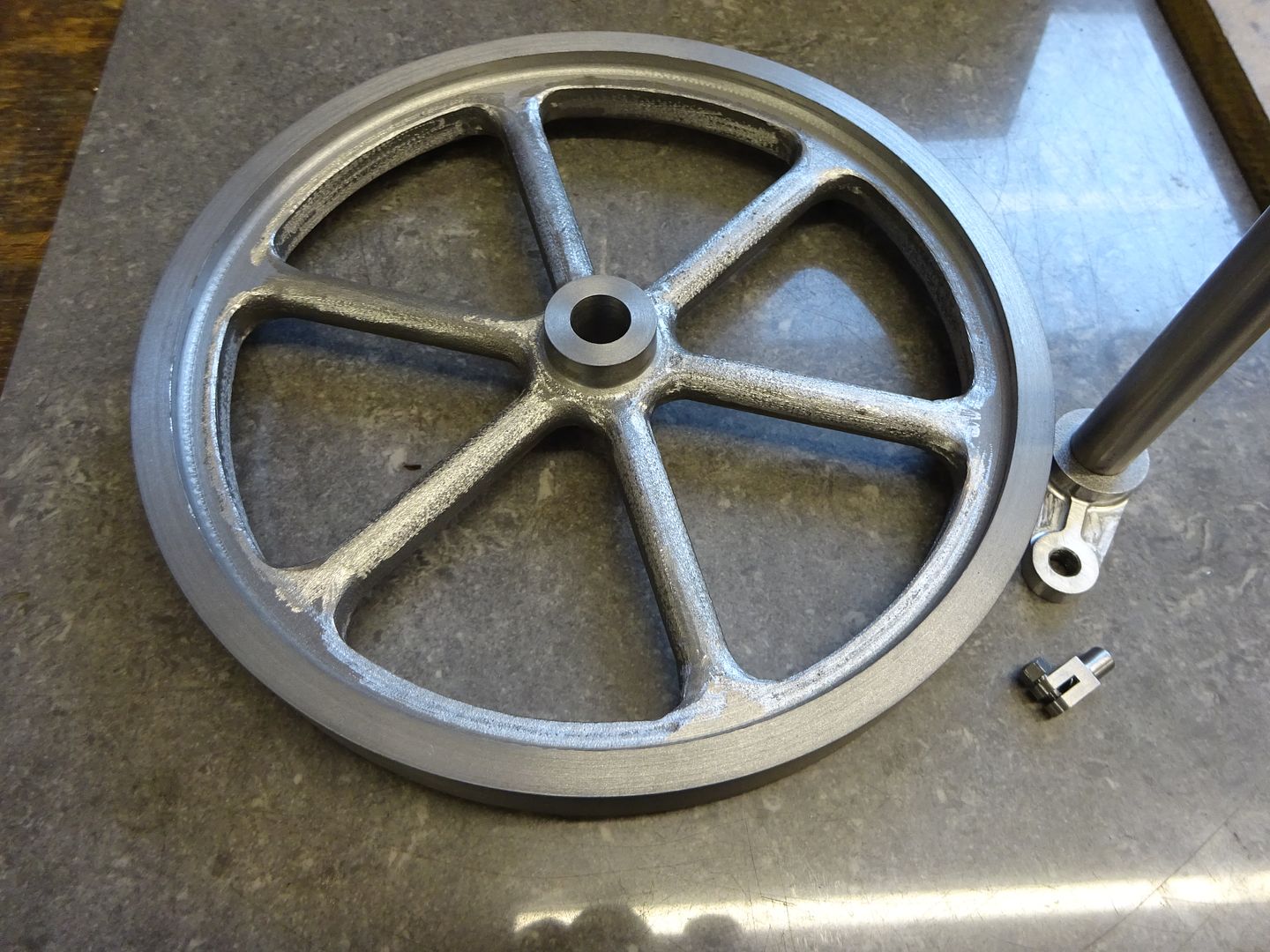

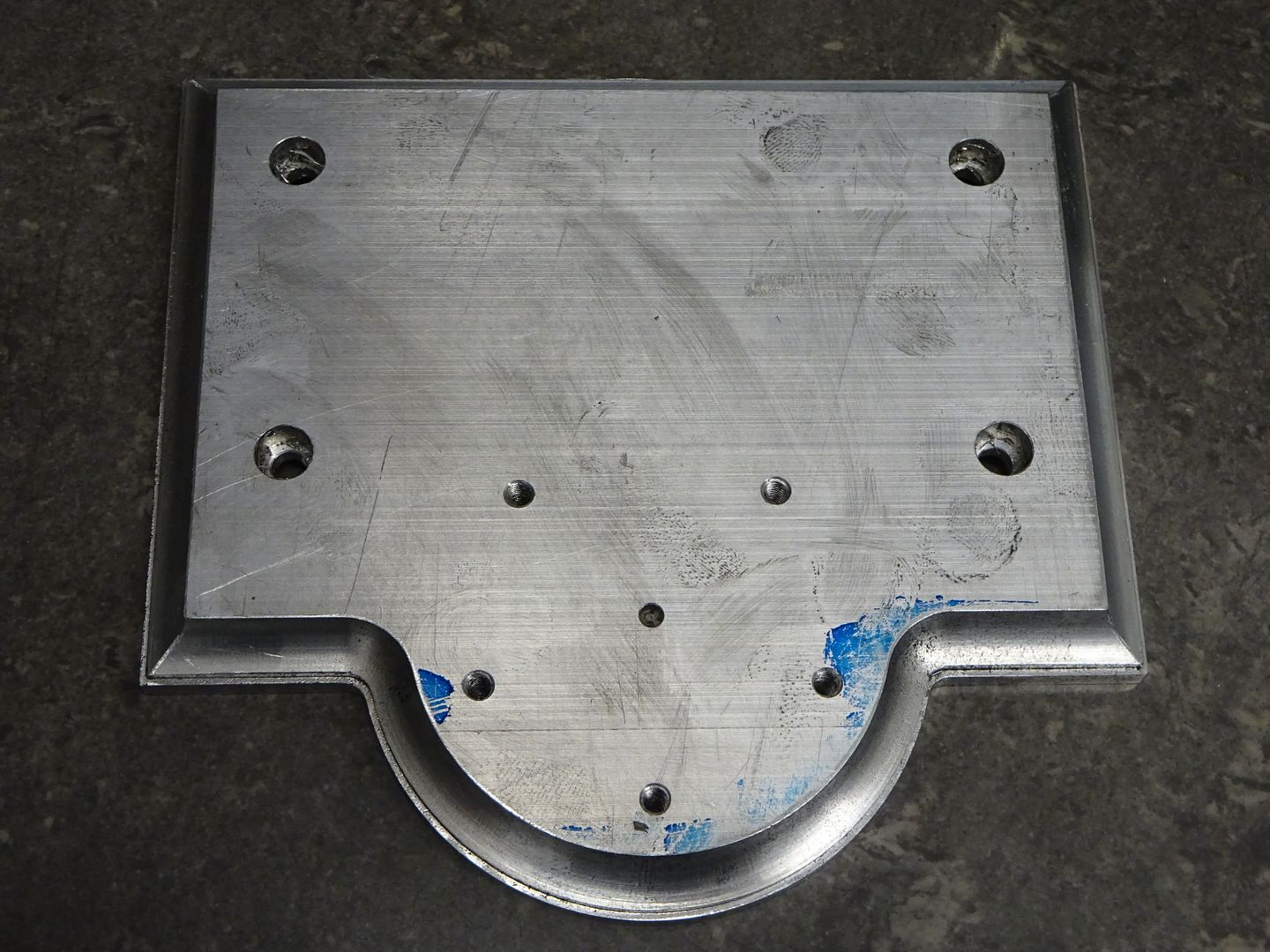

The completed base which to my eye has a much more interesting overall shape and the moulded edge looks a lot nicer than the rather plain original. Plus with materials at 1/4 the cost of the casting and a bit more time needed to machine you are getting better hours enjoyment per £

Edited By JasonB on 28/05/2022 17:05:50

Dr_GMJN.

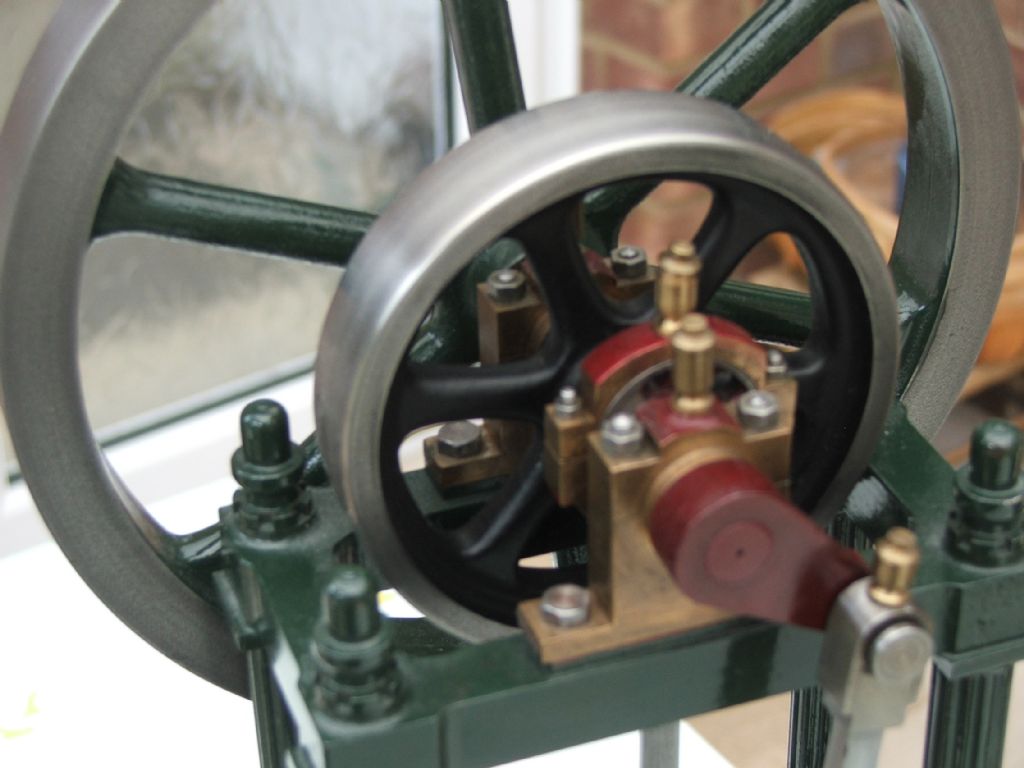

![20220525_164841[1].jpg 20220525_164841[1].jpg](/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/images/member_albums/44290/908375.jpg)