More contemporary material relevant to two disasters…..

Failure to understand wind loadings were certainly a major part of the Tay Bridge Disaster, but one of several reasons. The others were:

– Serious design faults: possibly the use of cast-iron for the columns, but also the spans were not bolted to them. Instead they were kept on their seatings simply by their own weight. Cast-iron had been a common material for columns and plenty of Victorian iron is still holding up structures like railway-stations, but is a poor choice for a bridge subject to high lateral as well as vertical loads – even when the castings are sound and geometrically correct.

– Appallingly sloppy workmanship by the contractors. The investigation revealed:

…..the columns’ castings were of very low quality, and their hollow cores were far off-centre;

…..the rag-bolts holding the iron columns to the masonry and brickwork piers were about half the length Sir Thomas had specified;

…..the brick-laying’s very low standard;

…..missing bolts or rivets.

Local fishermen reported having heard parts of the bridge rattle when trains passed along it.

– Equally sloppy oversight by the Board of Trade of both the design and construction.

Tradition claims the fateful storm was unusually fierce even for the area, but it seems that was not correct. It was a powerful gale but not unusually so.

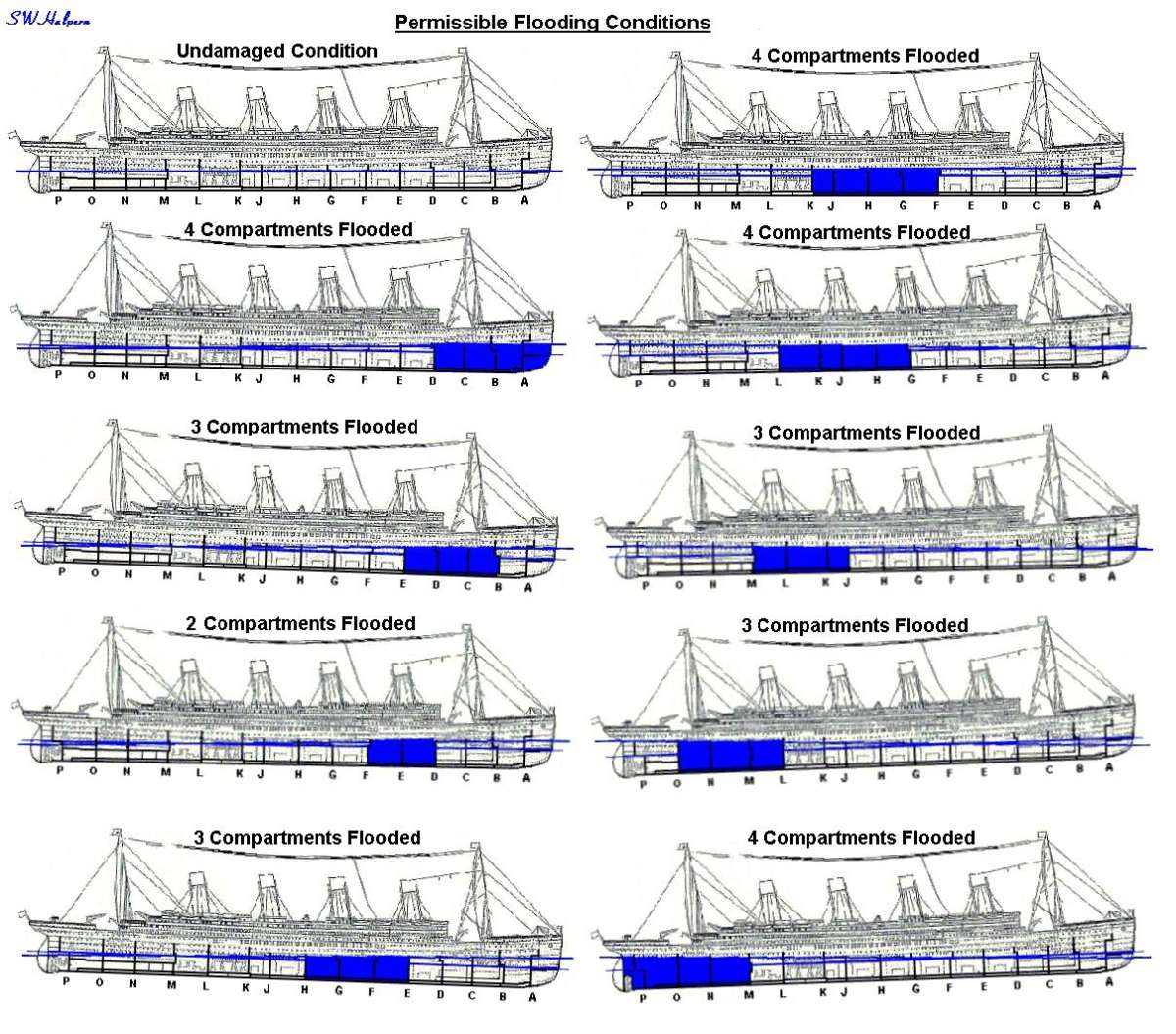

The Titanic and her sisters were designed and built to above the legal minimum standards, and to the high quality of materials available and expected, at the time.

[Ref:

The Engineer, 125-year Anniversary compilation, pub. Morgan-Grampian 1981; pp42-47.

This magazine is aimed primarily at professional engineers in senior managerial and directorial roles. The Anniversary edition covers its contemporary attempt to report on the disaster and the Inquiry, and describes how that was hindered by the Government refusing to allow it to photograph the bridge wreckage. The 19C edition outwitted that by discreetly obtaining photographs but printing etchings made from them – reproduced in the 1981 publication!]

””””

So how did The Engineer cover the Titanic‘s loss almost 33 years later? (Same anthology)

The 1981 anthology showed it had covered the Inquiry and the reporting as much as the technical aspects, but also made some unexpected comments.

It examined the question of speed. Had the ship been moving at half-speed, about 10 knots, the force of the collision would have been quartered, but also the estimated time from spotting the iceberg to hitting it would have doubled from one to two minutes, perhaps giving more chance to evade the ice. However, it also points out, the passengers expected a rapid crossing! It wrote:

“….. But that a modern liner should travel at … 10 or 11 knots for a whole night is inconceivable. Passengers would rather run the very distant risk of collision with an iceberg.”

I suspect the survivors may have have begged to differ, though re-thinking that, the author was probably right that the passengers would have thought such a collision very unlikely. They would have had full trust in the ship and her crew.

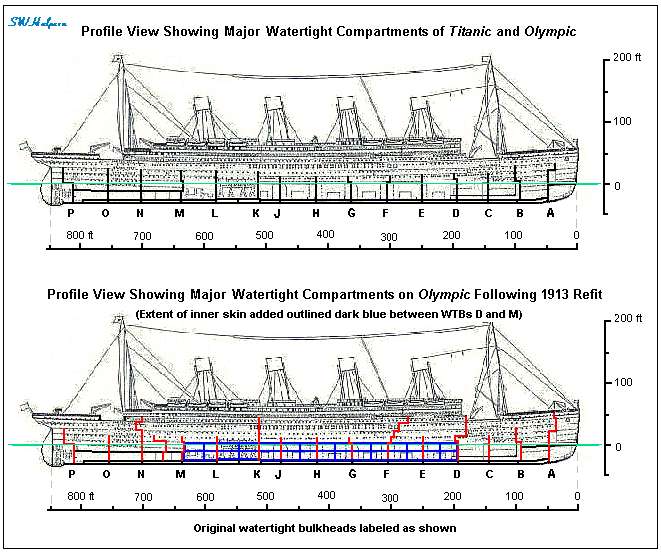

The magazine had previously examined the question of double-hull construction, but suggested the complicated joining of the two skins would not necessarily save the ship due to the damage to the outer being transmitted to the inner. It did though agree with a strong public demand for full lifeboat and raft provision for all on board.

Lest we think the magazine’s pre-WW1 staff were rather hard-hearted, they were not.

In fact after an elegy that reads as more for the ship than the people, a subsequent edition carried a memorial to the engine-room staff, noting they had probably all stayed at their posts to their end, and even more, printing a list of their names.

Later, it recorded the efforts by the Institute of Marine Engineers and “a special committee of Liverpool gentlemen” to raise a memorial to the Titanic’s engineers, and gave the addresses for contributions.

It would be interesting to know which if any of the public newspapers of the time were as thoughtful.

.

Finally, The Engineer pondered if a 19C invention may have avoided the disaster.

Its July 1864 edition had recorded an ice-warning system invented by A. Bryson, which had ‘received a most favourable report’ from the Royal Scottish Society of Arts.

[There seems to have been much less of the divisive Science / Arts / Crafts splits in the 19C, than we see nowadays. Perhaps engineering was much more obviously to non-engineers, the amalgam of scientific knowledge and creative crafts that it is.]

The instrument warned of an iceberg by using electrical signals generated by the temperature differential (in air or water is not stated) to sound an alarm on the bridge; and was estimated to cost ‘no more than £50 to produce’.

Yet by 1912, 48 years later, Bryson’s iceberg detector ‘… had sunk without trace.’

Nigel Graham 2.