Fundamentally its all about preventing the chip from jamming in the cut.

By the very nature of the cutting process the chip is wider than the slot so it either has to be folded or deflected sideways if it is to come out cleanly. Proper lubrication of the slot sides, preferably by spray or flood, will clearly be a great help.

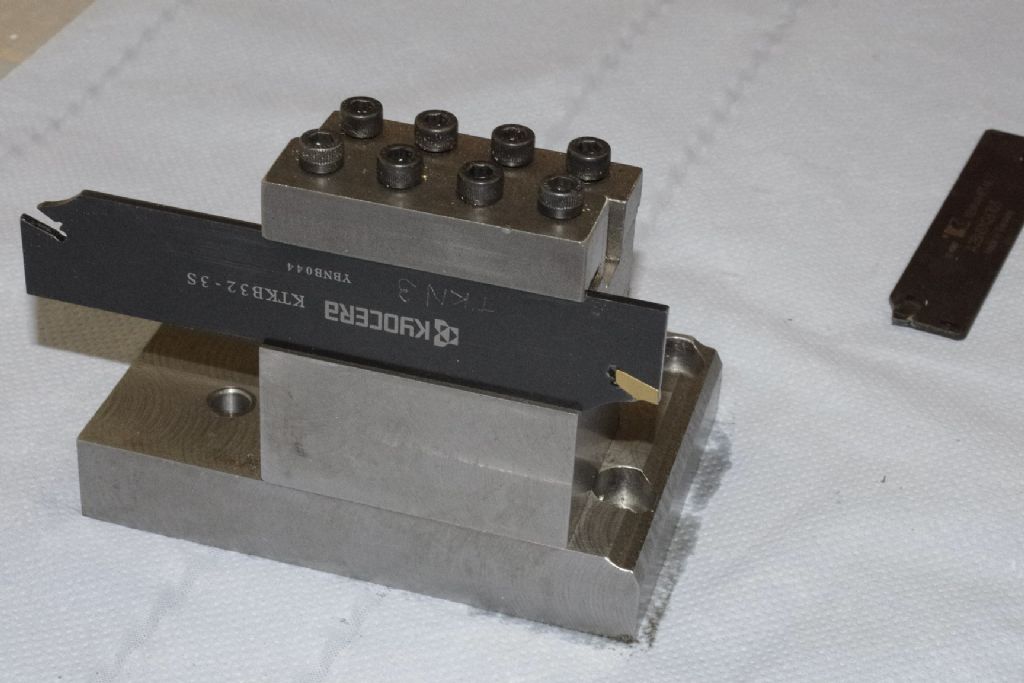

The V shaped top of modern insert tooling effectively folds the chip for easy evacuation. Being carbide they can also run fast enough to soften the metal at the cutting point reducing loads. One thing to watch out for if not running at book speeds and feeds is the formation of a continuous coiled chip riding on top of the tool carrier blade.

If left to build up this will jam.

Often happens partway through the cut as the surface speed on the smaller diameter drops below optimum for that particular material. I find the effect is generally limited to a certain range of diameters and speeds for any given material. My Smart & Brown 1024 VSL has continuously variable spindle speed so hitting the speed change button usually sorts it. More of a problem with fixed speed machines. On my P&W B I switch to manual feed and can usually clear the chip by varying the thickness.

When using an Eclipse or similar tapered blade grinding the tip with a slight side angle helps. The chip starts off at a slight angle to the slot and will tend to continue that way twisting a bit more to accommodate the extra width. As the cut should be very small, Andrews 4 thou per rev is typical, maybe 2 thou on a small lathe, there is little benefit in grinding a top rake. Dead flat top and really, really sharp works fine. Due to the taper top rake produces a small clearance a little back from the cutting tip just right to trap a ragged edge and grab it. Sometimes tilting the balance between just managing to cut and dig in when things aren't going quite as well as they should.

Obviously a thin continuous chip really helps. Which can be difficult to achieve by hand. Especially if nervously grumbling a long at low speed. Most folk tend to over-cut when hand feeding. If, for any reason, the tool fails to cut next time round it will try to take a bigger cut needing more force. Doesn't have to happen for many revs in succession before you have serious dig in issues. Usually with the tool trying to climb over the work as the first step to disaster. The stiffer the machine and set up are the more likely it is that sufficient force can be generated to overcome a temporarily failure to cut before the problem builds up.

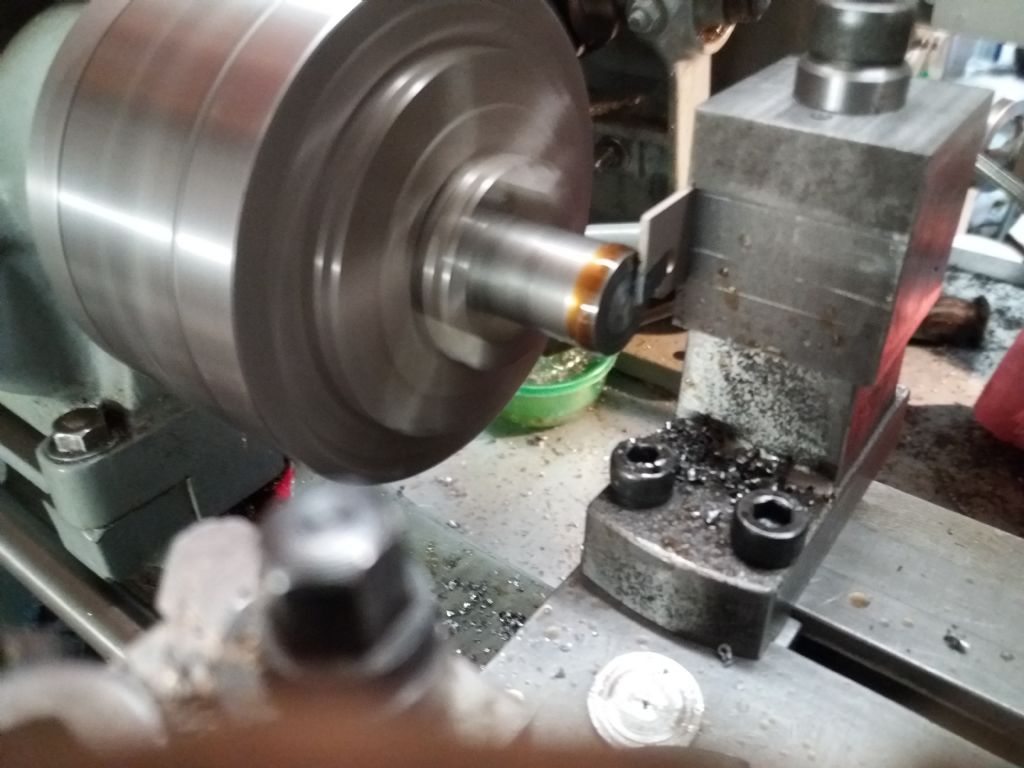

The rear tool post carrying the parting tool directly on the cross slide is a good engineering solution for small machines. Not just due to eliminating all the potential sources of flex in the top slide but also because it usually causes the feed screw to operate in tension.

Conventionally the feed screw pushes the tool into the work so, due to the screw helix, there is a slight sideways component to the forces causing it to bend fractionally. For practical purposes the push force goes through the core diameter of the screw so, on our small machines, it is significantly slimmer and weaker than it appears at first sight.

Effectively its a very stiff spring.

So if you are supposed to be cutting 4 thou per rev and it takes two or three knocking back revs to build up enough force to start cutting again the extra force is generated by the spring effect. Once it actually starts cutting again the tool will spring forward and get slightly ahead of your feed. Classic conditions for "pilot induced oscillation" and chatter. Hopefully there will be enough damping to get things back under control but this isn't always the case and a jam up will probably occur soon. Not always. My first SouthBend 9" would often happily settle into a steady 1/16" or so back and forth motion of the cross slide during parting off for this very reason. Jam up / no jam up about 50 – 50. Cured by an extensive overhaul. Don't recall ever finding the specific reason but it was well used and everything was slacker than ideal.

With a rear tool post the screw acting in tension is effectively inextensible so you don't get the spring effect. Everything is much more under control. On a small machine you have a more positive feel of what is going on in the cut too.

An further, often overlooked, benefit of a rear tool post is that its worth taking the time to set the tooling up just so for absolute best results. When changing tools, even with a QC post, close enough rather than just so is usually the norm. Sometimes close enough doesn't quite cut it.

Clive

Edited By Clive Foster on 10/06/2020 14:05:28

Martin Connelly.

Martin Connelly.