I wrote this six years ago (I know becauise I'm not 46 any more!), then decided others know better than me.

Happy to receive criticism of it – it may be complete nonsense to anyone else… and shape it up as a proper article, Valves I designed this way have worked!

Neil.

Designing Simple Slide Valves

In the dim past, Model Engineer used to have a section for queries, separate from the main letters page. Readers had to write in enclosing a small voucher printed in each issue, to receive a response from luminaries such as ETW or even Percival Marshall himself. These enquiries were often very practical, such as "where can I get castings for X?" or "how many turns are needed to rewind motor Y for 240 volts?".

I think it would be a marvellous idea to recreate such a feature; I have benefited from the advice of the editorial team on a number of occasions, and I would have had no qualms about this correspondence being published. Perhaps, if other readers agree, the editors will consider this suggestion?

Aside from the perennial rewinding of various electrical coils (at 46 am I one of the youngest people who remembers winding their own transformers by hand?), one of the commonest requests was for the dimensions of slide valves.

I have designed a few simple slide and piston valves, all of which have worked, and it has struck me that, though their design appears complex, it can be boiled down to a few simple rules of thumb.

I am not going to pretend to be in the realm of who will give you a marvellous formula for lap, lead, port sizes and steam chest volumes. I am just thinking of anyone designing a simple engine and who wants to set out sizes for a valve that will work in the space available.

The example which started my chain of thought was a small table engine described in an old ME, accompanied by a small but clear two-view sketch. The full size engine had 13" stroke and 9" bore and a 4' 3" flywheel on a table 4' 6" high. From these dimensions and the sketch it was apparent that the valve chest would be about 3/8" deep and 1"long. The eccentric strap would be about 1/2" diameter. The width of the valve chest could not be calculated, but a sensible proportion would be about the same as the cylinder bore of 3/4".

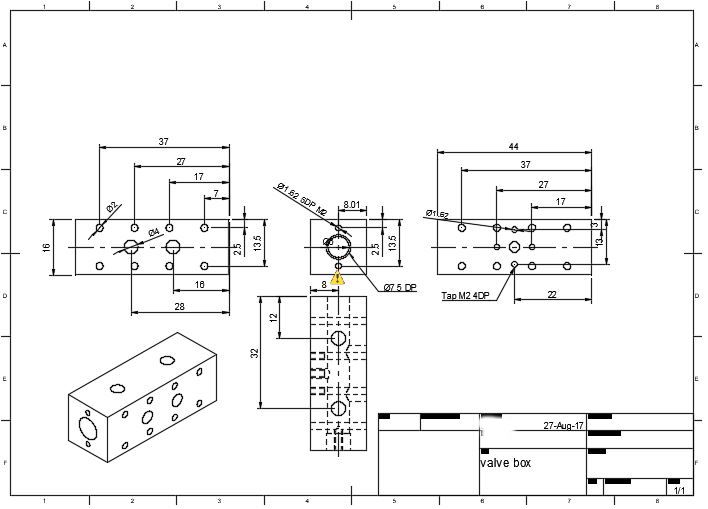

From the point of view of setting out the valve and eccentric there are two important dimensions:

1 Port width which should be a large as possible, to allow free passage of steam.

2 Valve travel – which is limited by the size of the valve chest and the eccentric.

The two arbitrary steps which makes it easy to link, and therefore fix, these dimensions are to make the port width and spacing equal, and assume that the steam ports close and open exactly as the exhaust ports do the opposite. Now this means, for example, that the exhaust port will not be larger to allow free passage of the exhaust. For the typical model that will not be doing hard work, fine tuning is not critical, and most importantly valve gear to these specifications will work and will only need one adjustment – setting the eccentric angle. In any case, once a valve has been laid out with equal widths, it is relatively easy to make adjustments.

Let us assume a port width of 'x' . A look at Figure 1 shows how all the other critical dimensions follow:

Port width = x

Port spacing = x

Valve travel = 2x

Valve length = 5x

Valve cavity length = 3x

Eccentric eccentricity(!) = x

Less critical dimensions, which can be varied, are:

Port width ~ 3x

Valve width ~ 5x

Valve cavity width ~ 3x

Steam chest (internal) length >= 8x

Steam chest (internal) width >= 6x

Steam chest(internal) depth >= 4x

Distance from slide valve rod centreline to valve face ~ 3x

Typical diameter of slide valve rod = x

SillyOldDuffer.