Always three factors to check:

Four, if Process is counted, but process is generally a combination of the first three.

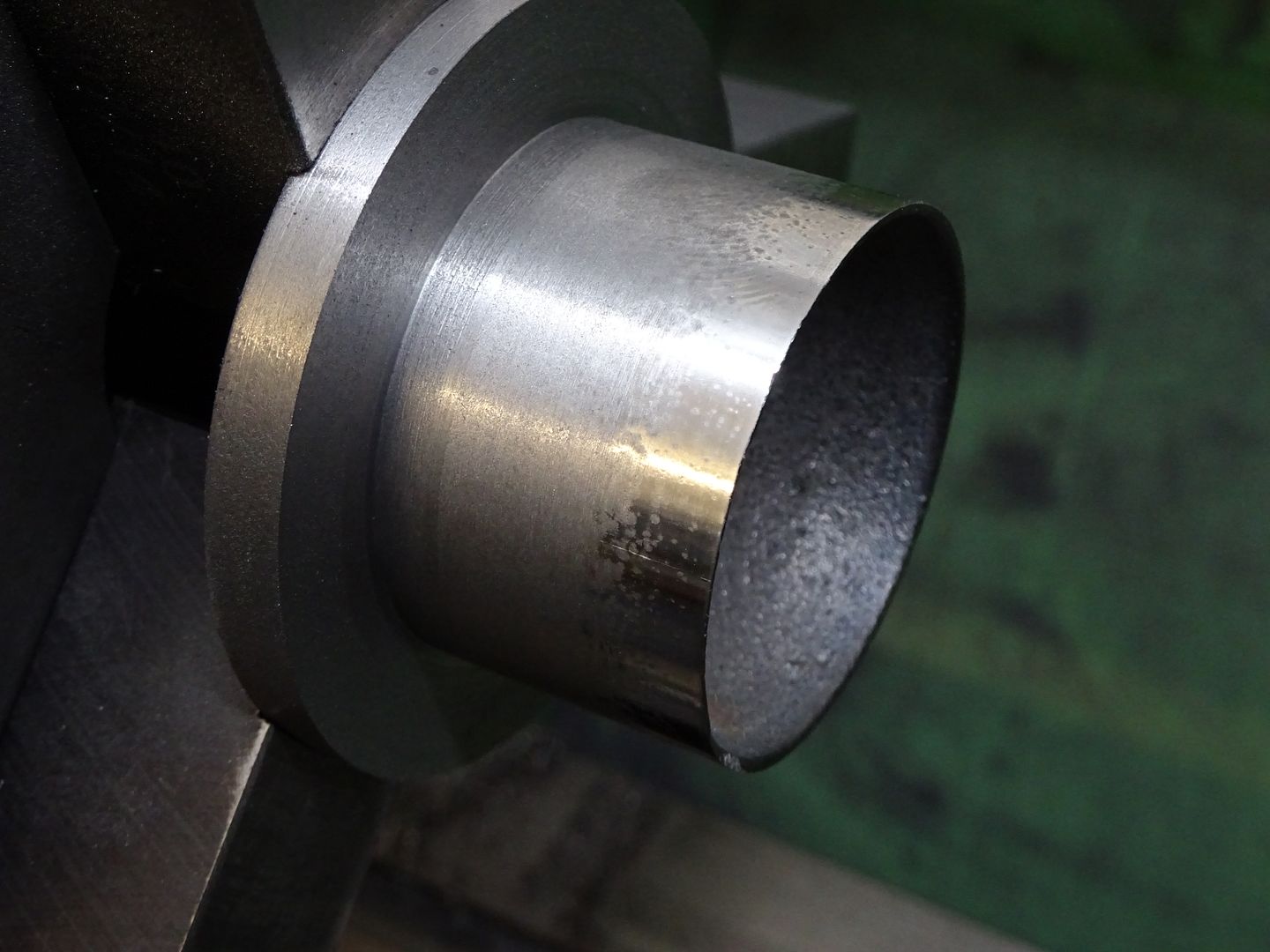

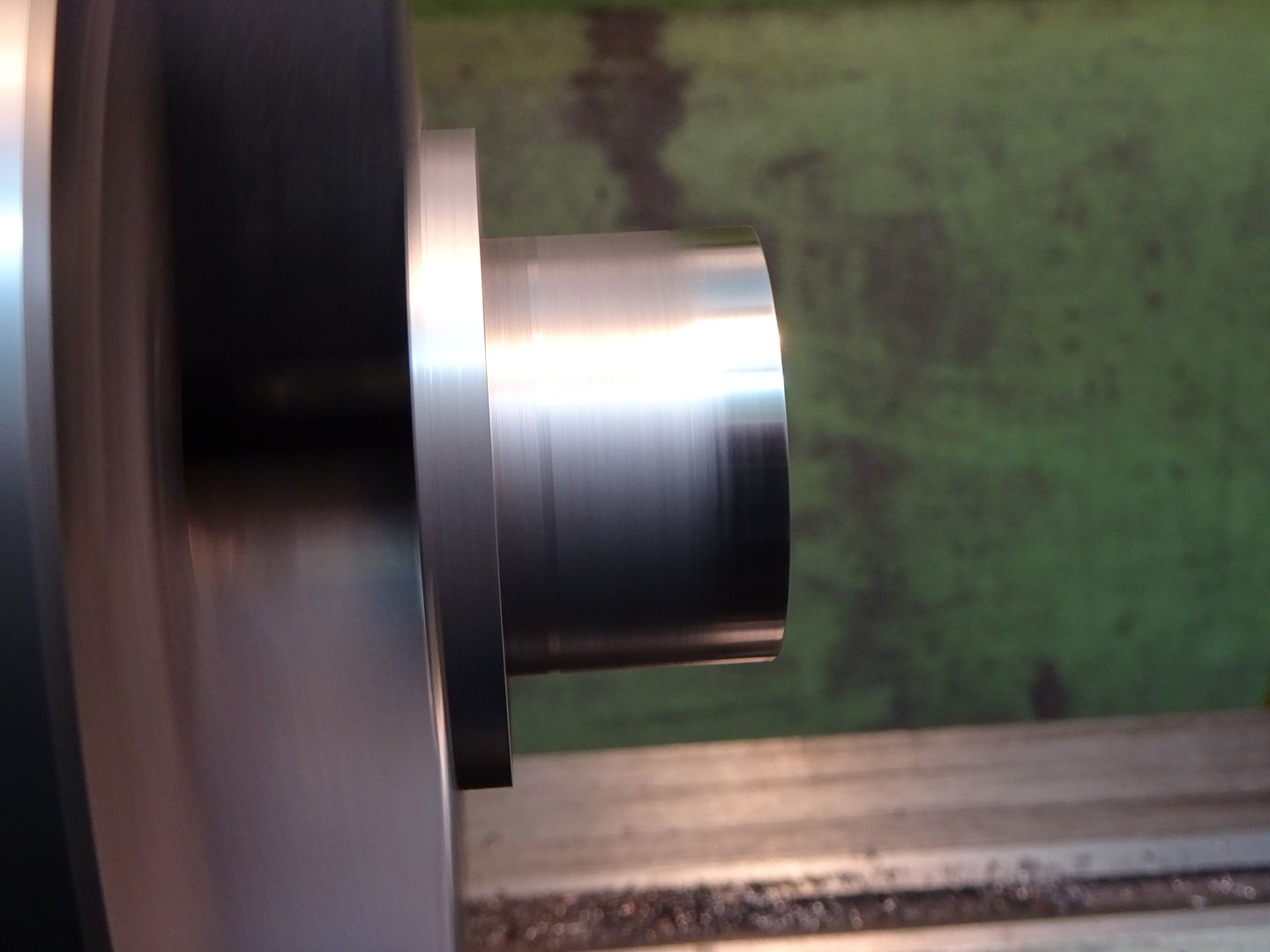

The material is cast-iron. It's famous for developing a hard outer skin if chilled rapidly, therefore a suspect. As pointed out, unlikely in this case because the iron would have to be heated close to red-heat and then rapidly chilled, perhaps by plunging into cold water. Most Loctites break at about 200°C, well below the temperature needed to chill cast-iron. Most metals work-harden to some extent but I'm not aware it's an issue with cast-iron

The tool presumably a twist-drill. Drills that perform adequately in wood may not last long on metal. Tool-steel drills blunt rapidly if allowed to get too hot, and a cooling fluid is almost essential. Metalwork, and most woodwork, is done with HSS drills. They're tougher and have three to five times the heat performance of plain tool-steel; last longer and are harder to blunt by accidental abuse. The performance of a twist-drill also depends on the accuracy of the cutting edges. The drill has to be accurately ground to a symmetric geometry. Cheap drills are often poorly ground, and reliable brands sometimes drop the ball. Possibly an out-of-adjustment machine produces a number of inaccurately ground drills before the operator corrects the problem. Needing a few in a hurry I took a punt on a large but cheap box of assorted small drills. The accuracy of the cutting edges varies from good to awful, so they have to be inspected with a loupe before using them. Rejects are binned immediately. Better drills give longer service but cause nothing but trouble when blunt. They are likely to work-harden the material, or wander. At the first sign of poor cutting, stop and make sure the drill is still sharp (loupe), replacing if necessary. Be ruthless; twist drills are cheaper than ruined work! Performance drilling metal is usually improved by a cutting fluid, but not needed on cast-iron once the chilled skin is breached. Solid carbide drills are available for hard materials.

Operator error includes things like drilling too tentatively or too aggressively, perhaps getting RPM and feed-rate wrong. Joe mentions running in reverse! Even if noticed quickly, this is an excellent way of blunting drills and work hardening the metal. It can ruin a good new drill in a few minutes. You can guess how I know, blush. Another cause of rapid blunting is not clearing swarf from the hole. Mincing previously cut soft metal rapidly blunts edges and particles of hard cast-iron skin are a brutal abrasive. More common I guess is persisting with a drill as it gradually grows blunt. Once the edge starts to go, drills blunt rapidly, especially cheaper ones. Misjudging when to use cutting fluid is another problem: lubricates and cools, and applied vigorously washes swarf away too. Often as not the difference between a beginner and an expert is the time taken to realise what's wrong. Beginners are inclined to plough on regardless, whilst experienced folk realise something is wrong, and, having seen it before, stop and adjust before trouble escalates. Beginners suffer more bad luck than most!

I like Joe's suggestion. If not, I suspect not realising the drills are blunt, either because they were too cheap in the first place, or damaged by operator error. I'm self-trained and it was very noticeable how the 'quality' of my tools magically improved as I learned how to use them properly. I reckon I'm clumsier than average, and perhaps the effect is less obvious to talented people! Anyway, might explain why this job went wrong even though John's method sounds OK. Unless the cast-iron was blasted up to red-heat!

Dave

Ramon Wilson.

Ramon Wilson.