I recommend starting by using the lathe to cut metal rather than measuring. Measuring is difficult and understanding the results more so. Getting either wrong can lead to unnecessary remedial work and making the lathe worse.

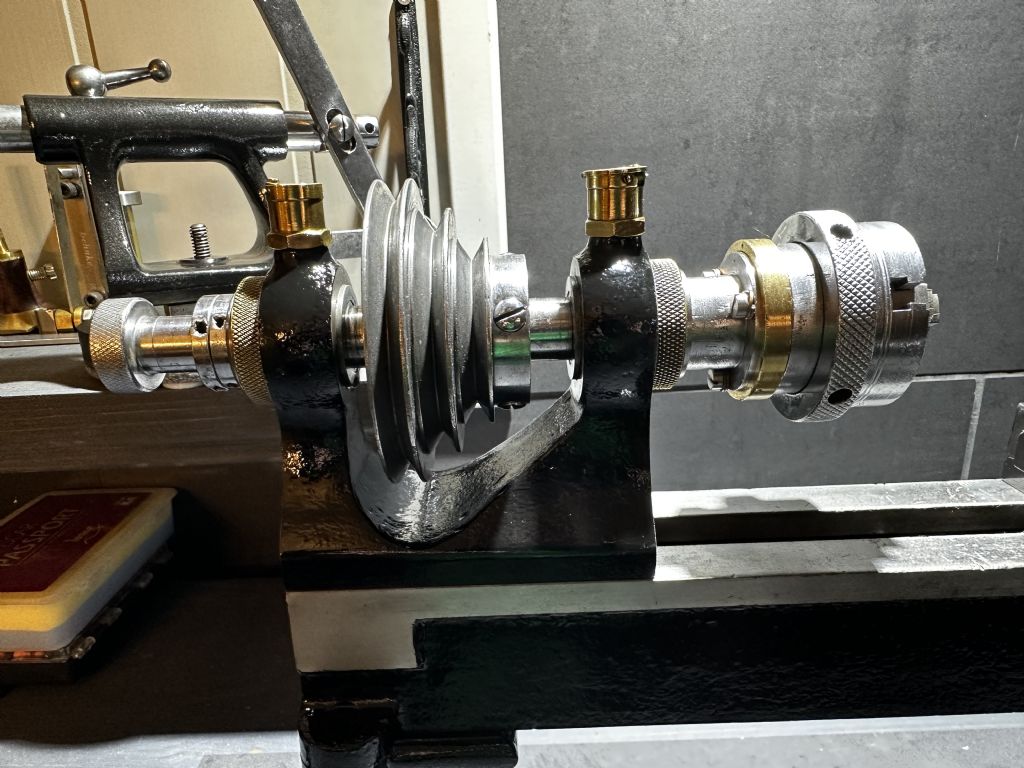

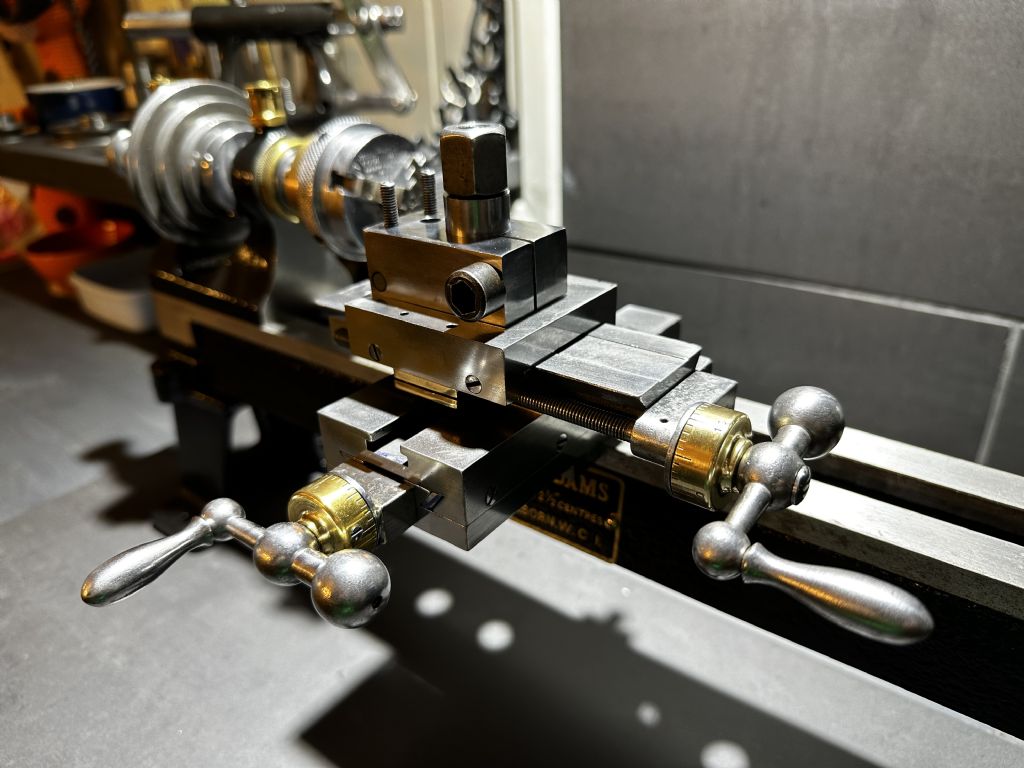

In contrast, cutting metal is relatively easy to do and it makes faults very obvious. Bent spindle, knackered bearings, head and tailstock misalignment, loose headstock, unacceptably worn bed, worn jaws, damaged chuck internals, cracked parts, broken keys, broken & maladjusted gibs, worn worms, backlash, broken shear pins, jambed collars, missing parts, blocked oil-ways, damaged nose thread etc. Running a lathe reveals problems that are hard to measure – like overheating bearings and horrible mechanical noises!

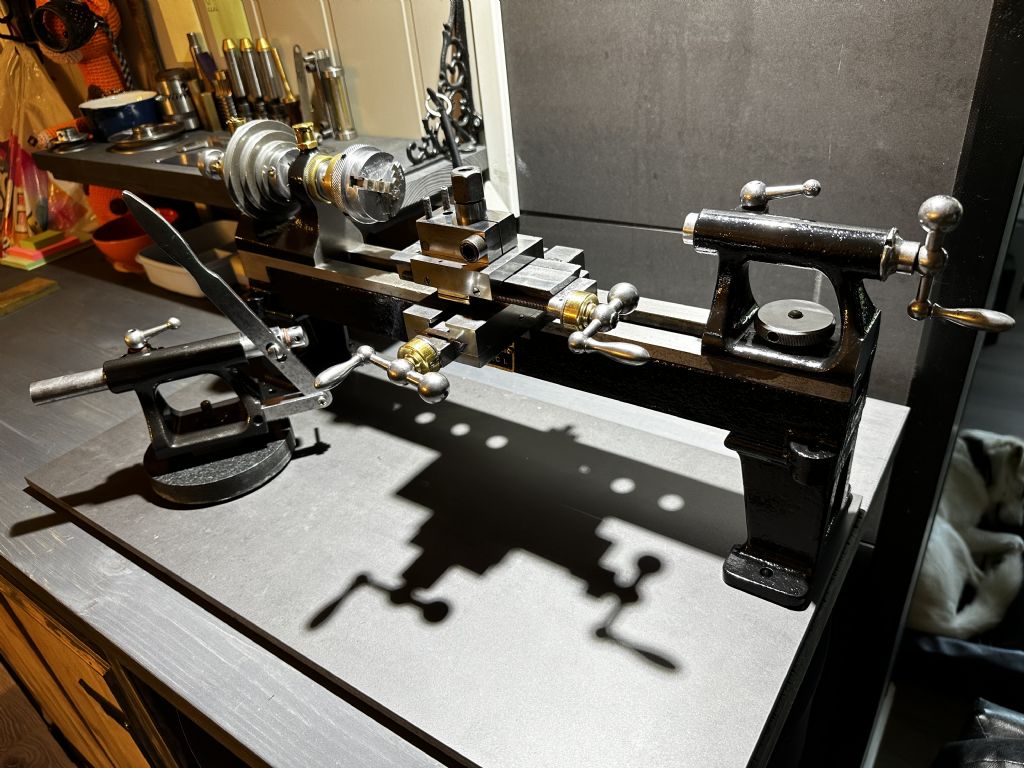

Many of these are cheap easy fixes, others difficult and expensive, possibly show-stoppers. Although she looks lovely, that lathe could be BER. (Beyond economic repair.) I advise putting the lathe 'as is' through it's paces to identify as many faults as possible before deciding what to do about them.

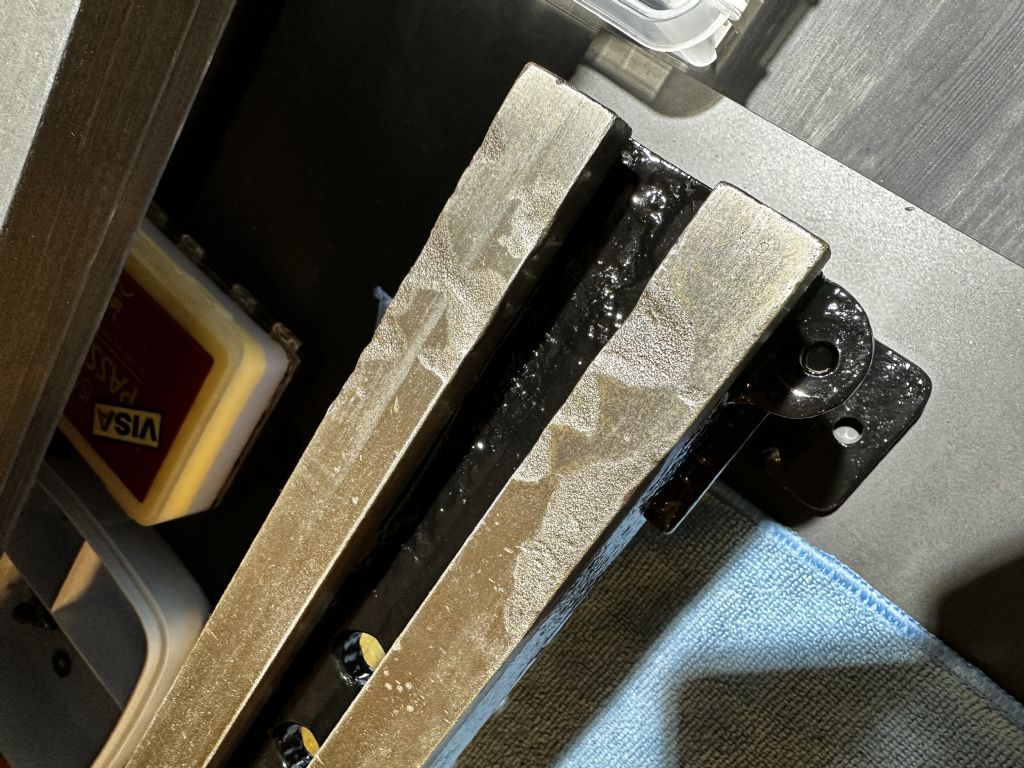

So don't start by laying a straight-edge on the bed and going immediately for an expensive regrind! Cutting metal highlights other issues, and the bed may not be worth fixing. A rust pit under the tailstock is unlikely to matter, whereas a deep hollow ground into the headstock end is trouble. But note it's possible to do good work on a rather badly worn lathe – how important the wear is depends on what the lathe is used for. Don't fixate on the bed or anything else: before spending money, cut metal and evaluate whatever it reveals.

With luck cutting metal will allow everything that matters to be fixed in short order. But cutting may only the first step. Although a good way of identifying lots of problems and giving a rough idea how serious they are, measuring is the next step, and essential for fine adjustments. For example if a DTI or micrometer shows the happily working lathe cuts a taper, measurement is needed to identify and correct the cause – might be bed-twist, which is fixed by "levelling", or the headstock needs realigning. Both are delicate adjustments.

I would only buy the lathe in it's present condition as an ornamental antique. It's obviously been beautifully cleaned up, but she's a very old lady, and condition as a working precision machine is unknown – could be anything between good or scrap. Unfortunately it's not difficult to tart lathes up, and anything of that age looking that gorgeous makes me suspicious. Appearance is secondary to me. Buying a second-hand lathe for work rather than decoration, I'd insist on seeing it run before buying it.

That said, lathes are fairly robust, and quite a few ancient survivors are in remarkably good condition. It depends on the machine's history – many were thrashed by men working hard to earn a crust and were scrapped decades ago. Others were used for light repair or prototyping work. A few sat on a bench, or in a crate, for 50 years. Lathes owned by hobbyists mostly have a very easy life. Not unusual for good lathes to end up rusting slowly away in a damp cellar, in which case the damage varies from fatal to cosmetic. When an item becomes BER depends on how much time and effort the owner wants to spend. In my case, not much, because I own tools to use them. But restoring old equipment is a respectable hobby in itself. Men cheerfully spend years bringing historic gear back to life. Heritage repair may not be for me, but I admire those who do it, and their results.

Regrinds – anyone able to name any firms doing this work at the moment? They seem to be disappearing.

Dave

Howard Lewis.