Don't be disheartened Margaret! I'm 8 years into the hobby, and – so far – haven't felt the need for a QCTP.

As you've found fitting a QCTP can turn awkward, and when this happens a beginner might not have the skills needed. So step one is to build skills, basically starting by making very simple objects, and gradually tackling more difficult parts.

I'm self-taught. I started by reading Sparey's "The Amateur's Lathe", which I found excellent. The book's only fault is not covering later technology like carbide inserts and DROs; not surprising – it was written in 1948! Next step was to collect a stock of scrap metal, then buy a lathe and start using it. I almost came unstuck at this stage because, by pure bad luck my entire collection of scrap was unsuitable – I'd picked up a range of alloys that were all difficult to machine – soft Aluminium, gritty Brass, hardened steels, and work-hardening Stainless. Driven by a beginner with hazy ideas about cutters, RPM, depth-of-cut, feed-rate and everything else, the mini-lathe didn't perform well. I was well out of my depth. Luckily, I was given a length of EN1A, which machines well, and that saved the day. Having made a start, stuff started making sense. I got a lot of help from the forum and still do. Many gaps in my understanding because I've learned haphazardly, not benefiting from an apprenticeship or mentor. (I suspect many internet videos are made by people like me because so many contain strange mixtures of good and bad practice. Watch them critically!)

Though I'm not a model maker, I found building a few engines extraordinarily valuable. They exercise:

- Reading drawings

- Planning work – which parts should be made first, and what sequence of cuts is needed to shape them

- Preparing stock – bandsawing to approximate size, removing scale from castings, marking up etc

- Setting up the lathe:

- Oiling and cleaning the slides

- Holding the job securely in the correct position: mandrels, glue, faceplate clamps, chucks, collets, steadies, centres etc

- Choosing a cutter suited to the metal and to the operation – saws, files, drills, knives, boring bars, taps, dies, etc

- Selecting and adjusting RPM, DOC and Feed-rate to suit the metal and operation

- Locking unused axes,

- Removing loose swarf, oil-cans and wandering tools away from the action

- Asking 'what could possibly go wrong?', especially checking that nothing will collide whilst the machine is cutting

- Driving the machine – a combination of managing sequences of roughing and finishing cuts, removing metal in a sensible order to get accurately sized parts, with an acceptable finish. Achieving the correct size requires understanding lathe dials, calipers, micrometers, DTI and gauges. Driving a lathe requires understanding the various controls, and being able to engage and disengage them at the right times. A 'feel' develops with practice: the optimum work rate is a balance between operator actions, machine capability, the metal, and the cutter.

- Dealing with Failure. As there's a lot to learn, most of us have junk boxes full of rejects. Very upsetting! It's all part of the game. If metal-work was easy it wouldn't be an interesting hobby.

My all time favourite learning engine is Stewart Hart's PottyMill. Neither too simple or too complicated. The finished engine works, and there are no mistakes in the plans. Though all the parts are within beginner range you have to think, apply various techniques, and maybe take a couple of goes to certain parts right. The engine does not require super-accuracy, and is fabricated from stock metal. As a learning project it offers the opportunity to make a crudely finished but working engine, then to develop the skills needed to produce a finely finished well-made version, and then to move on to smart paint-work, in a realistic historic mill setting, with Lancashire boiler, figurines, and factory chimney made of individual scale accurate bricks.

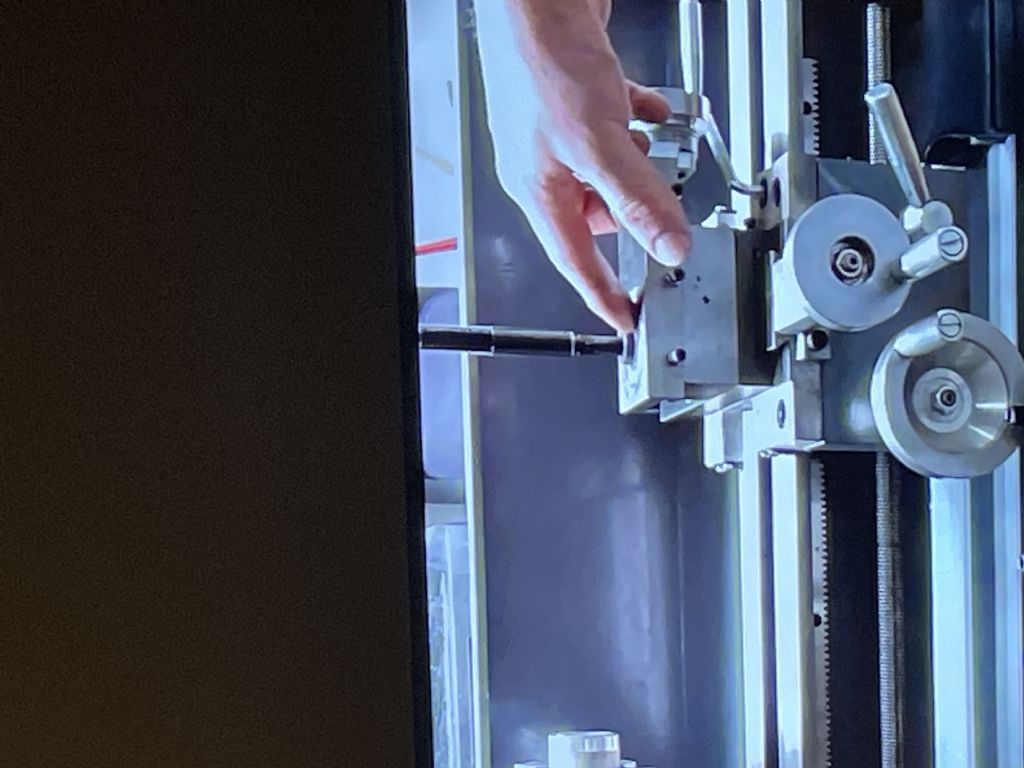

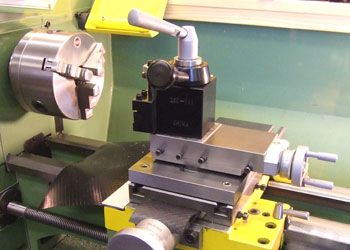

After making a PottyMill, the acquired skills make fitting a QCTP rather easier!

The reason I don't have a QCTP is I find carbide inserts pre-shimmed to height don't take long to swap in and out of a 4 way tool post. I think pre-shimmed inserts in a 4-way are nearly as fast as a QCTP.

QCTPs pay off when the operator favours HSS tooling (which have to come off for resharpening), or their particular work involves a lot of rapid tool swaps, which isn't typical of beginner workshops! There's another trade-off too – though tool changes are faster, QCTP are less rigid than a 4-way. I decided to spend my money on other tools, and have never regretted it. Has to be said though, that I work rather slowly.

As Margaret made good progress with a nasty tool-post problem, I say 'keep going'. Once a few basic skills are acquired, I'm sure a second attempt will succeed.

Dave

duncan webster 1.