Posted by Sam Stones on 29/01/2020 03:52:41:.

…

Q. Do ALL other clock designs beat at 1.0s?

…

No, far from it. Beating in seconds simplifies the maths and the resulting gear train(s) are mechanically satisfactory. (Not too complicated, and no need for extreme ratios.) Apart from that, it's not a constraint.

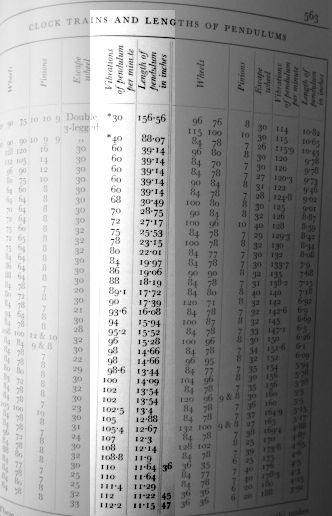

This table is from Britten's Watch & Clock Makers Handbook. Just to keep us on our toes it tabulates 'Vibrations of Pendulum per Minute' rather than seconds, but it gives the clockmaker a choice of 32 different periods.

The two times marked with an * are for Turret Clocks with a rotation time of 3 hours.

Another table explains lever clocks run at 16,200 or 18,000 vibrations per hour (4½ and 5 vibrations per second), and gives 7 gear trains for each. Three trains are given for "Non-Seconds" clocks running at 19,800 vibrations per hour and two more for clocks running at 21,000 vibrations per hour.

I like to think of clocks as consisting of an oscillator followed by a divider chain. In a mechanical clock the oscillator is a slow pendulum, balance wheel or verge. The divider is a gear train, essentially counting ticks and translating them into h:m:s. In an electric clock the oscillator is faster – mains frequency – and the divider is a synchronous motor turning a few gears. A quartz clock has an electronic crystal oscillator and an electronic divide chain. As it is extremely easy to reliably divide frequencies by two, the oscillator usually runs at a power of two, 32678Hz being common. A quartz clock ticking at least 650 times faster than mains at 50Hz makes it difficult to build a mechanical divider, so electronics are needed. The oscillator frequency is divided down repeatedly by 2 to drive either a digital display or analogue hands with a simple synchronous motor plus a few gears. One second out is quite common.

Although quartz crystals are excellent time-keepers, they're not the best that can be done. At the moment, this is the average of several Caesium oscillators running at 919263177Hz with human-useful frequencies derived by electronic dividers. Human useful can be almost anything: there are radio standards locked to atomic time at 10MHz, 5MHz, 198kHz, 60kHz and several other radio frequencies. (Almost any broadcast radio station can be made a reference.) Today, accurate time is mostly got from GPS satellites and the Internet.

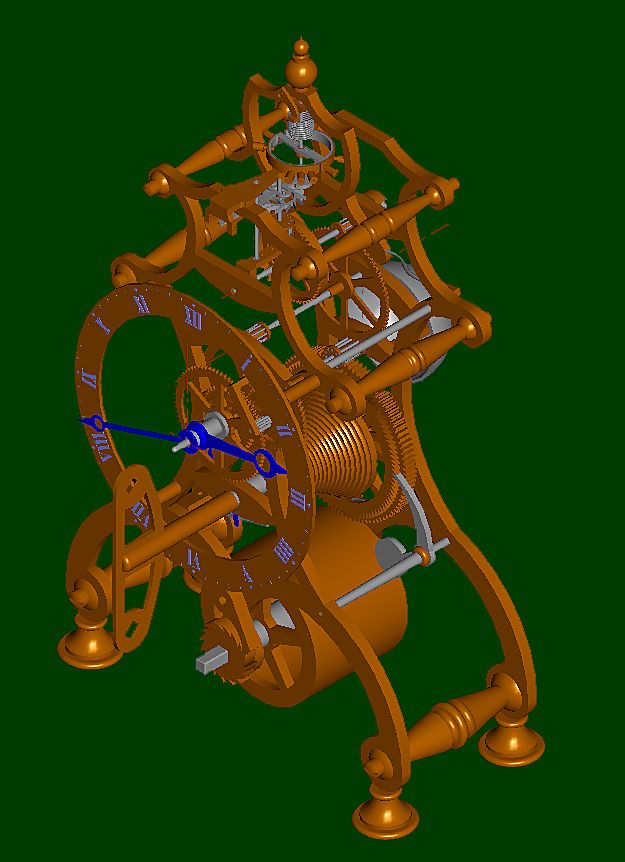

Sadly, although electronics have dramatically improved the quality of time-keeping for rock-bottom prices, they aren't half as aesthetically pleasing as mechanical clocks. Just like diesels vs steam locomotives, one is a brutally efficient tin box on wheels, while the other, despite being mechanically out-matched, is a treat for sore eyes.

Dave

Sam Stones.