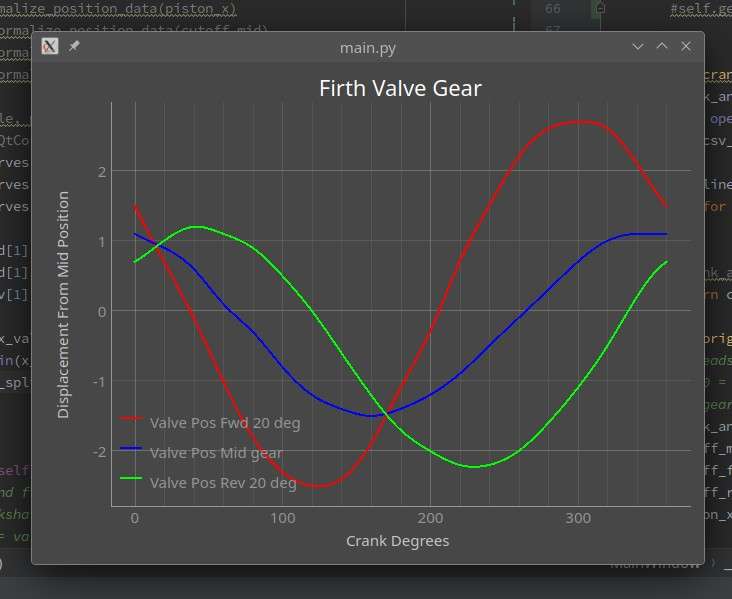

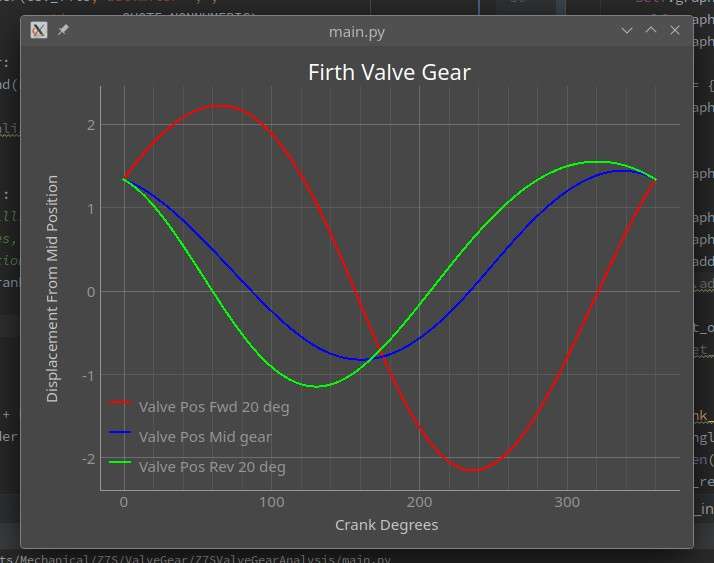

AsDave says, this is a fascinating thread.

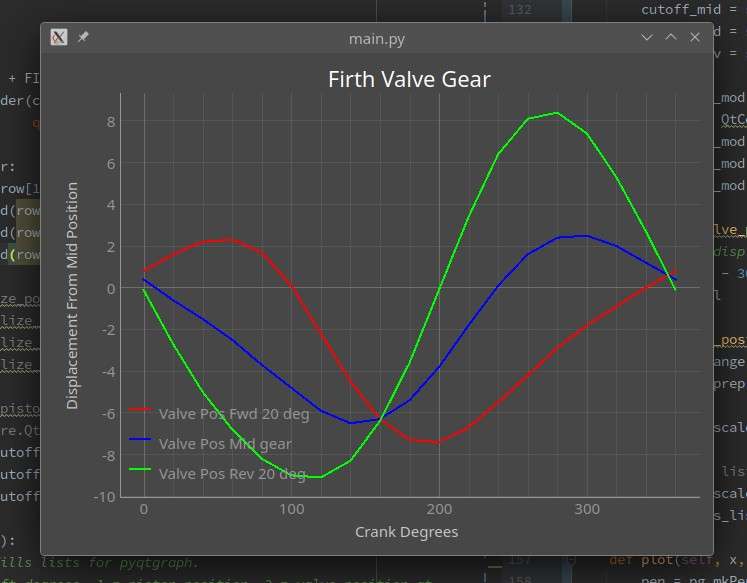

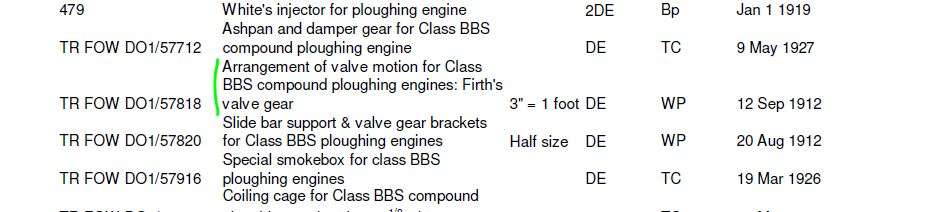

Previously I had not even heard of Firth Gear though I know there were quite a variety invented, of link-motions, radial-motions and assorted cam-drives.

I am not sure where the Mann steam-wagon gear fits, but I think radial. It uses a slotted eccentric moved across a square on the crankshaft, so was relatively simple, very compact and might give near-“perfect” valve-events although with harmonic rather than the rapid-action valve-travel of Stephenson’s gear.

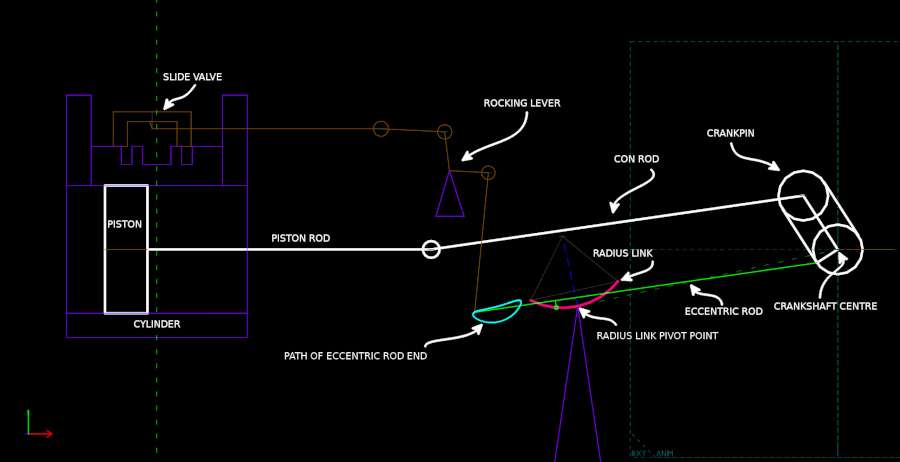

Stephenson’s Link Motion was probably costly to make simply because it contains so many parts: 11 or 12 between crankshaft and valve-spindle, omitting the reach-rod and control, and valve-spindle guide; and neglecting assorted pins, keys and fastenings.

Walschearts’ Gear (radial) has about eight per cylinder even if discounting some parts, such as the expansion-link and its lifting arm, being divisible into further bits.

One might imagine the most difficult and expensive component was the curved expansion-link, common to both gears; and that on locomotive’s Walschaerts Gear was sometimes assembled from several pieces. I doubt it was really very difficult, industrially.

Its critical area, the arcuate slot, could be shaped relatively easily using a slotting-machine with power-driven rotary-table, albeit starting with a large, drilled hole then cut in two episodes. I think an ME contributor (Doug Hewson?) pointed out fairly recently the links on some locomotives were made in four parts: two curved arms bolted together with intervening, large spacer-blocks. The really awkward bit may have been machining the outline!

The American company, Case, used a variation of the deceptively-simple Hackworth Gear (radial) on its traction-engines. This, if designed and set correctly, can give fairly good results from very few, easily-made components but such niceties were less of a consideration than sales and servicing cost when applied to very basic, narrow-gauge, industrial-site locomotives such as the Kerr, Stuart “Wren” class.

duncan webster 1.