Much as I love the banter of the tea room topics, I can only use those to avoid shop work for so long.

It is rather hot this time of year, with temps hovering around 100F every day, and about 70% humidity, so really no excuse is too flimsy to avoid shop work.

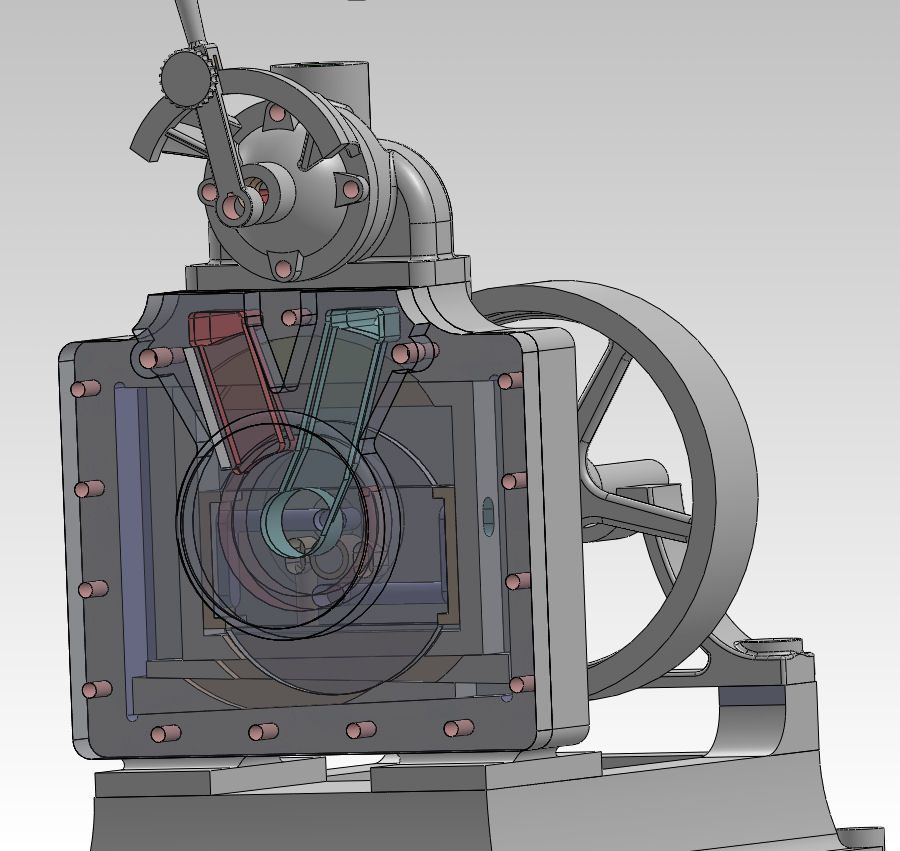

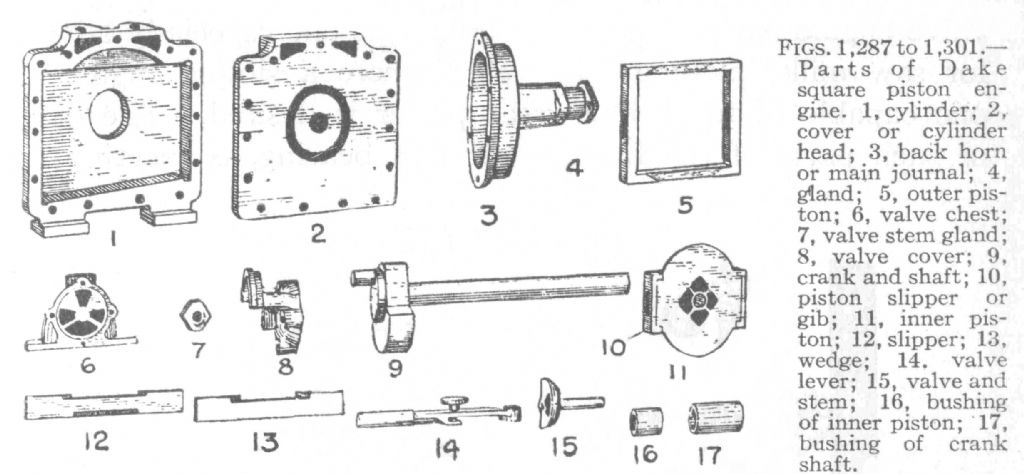

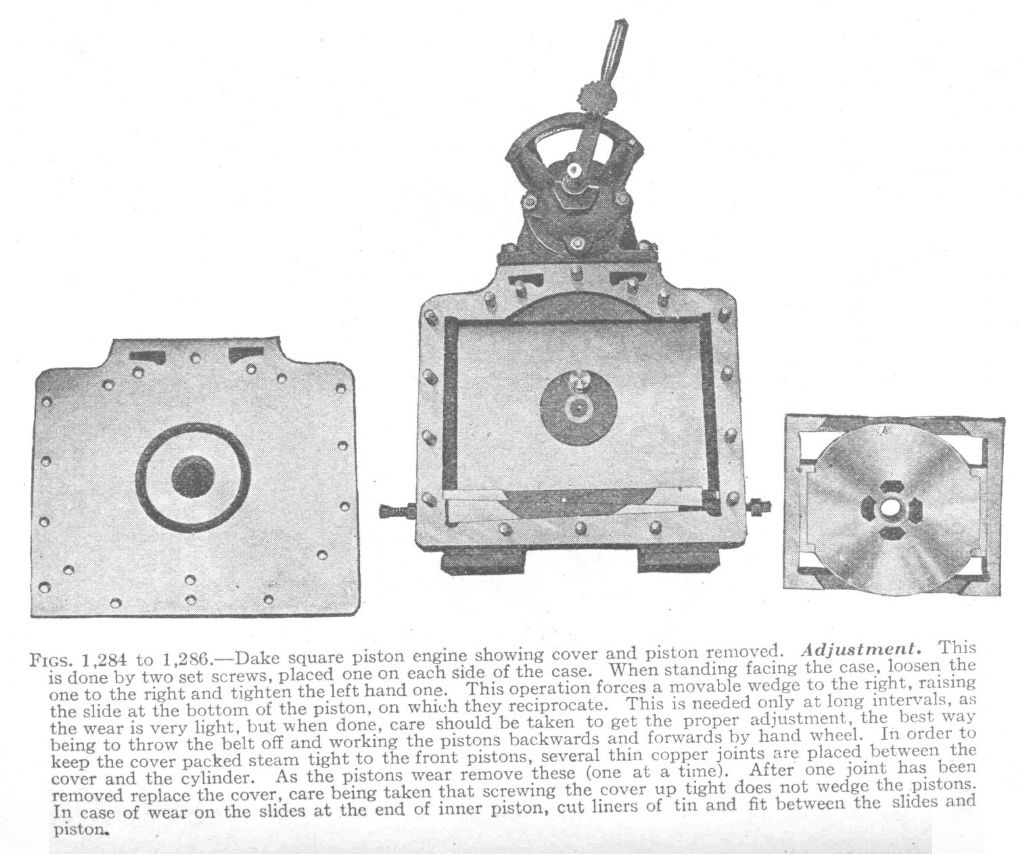

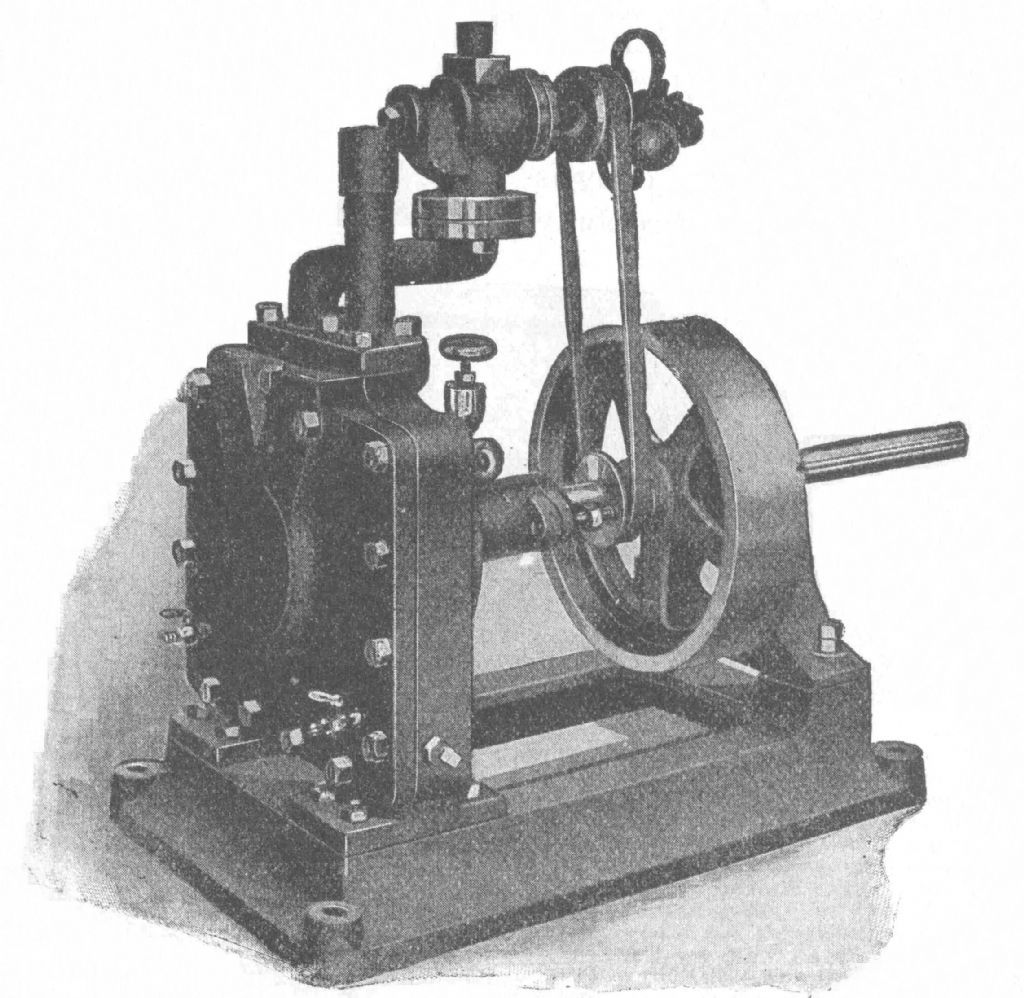

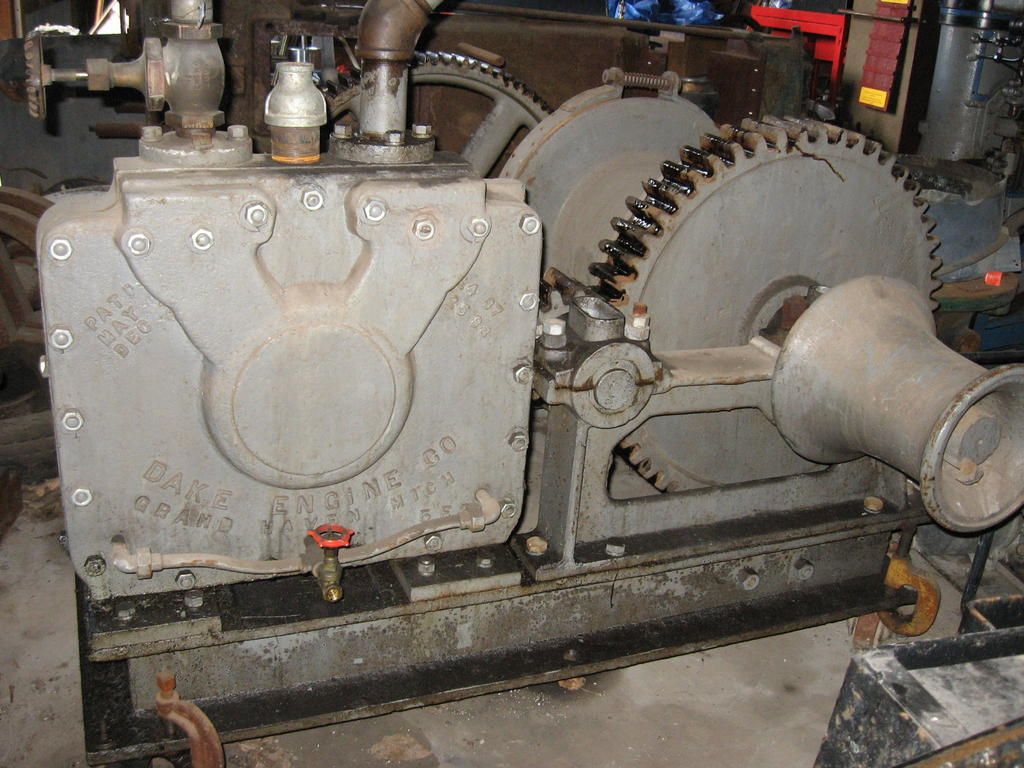

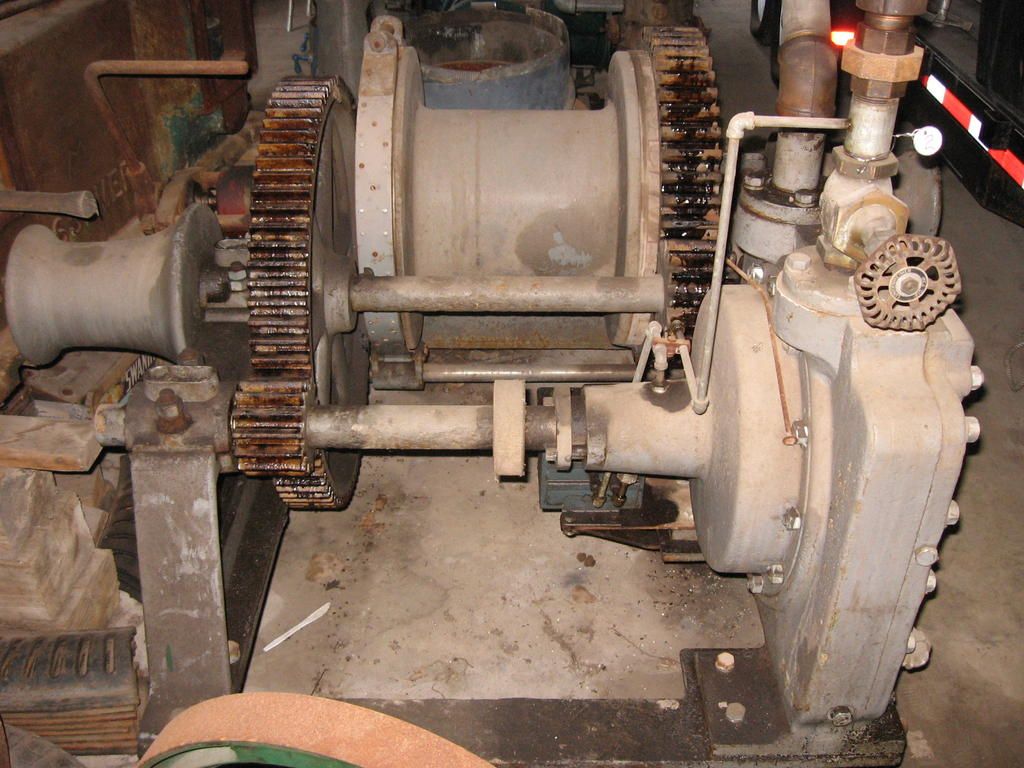

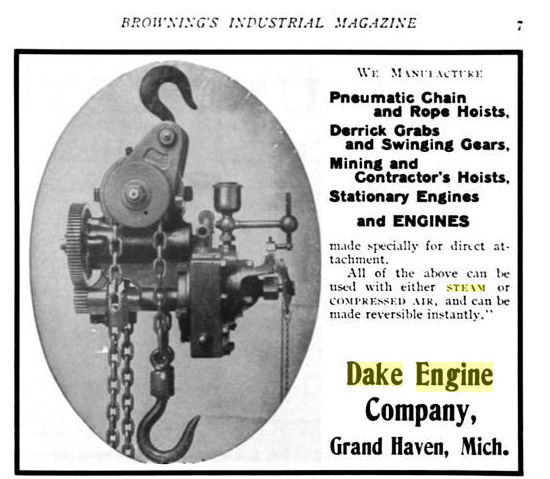

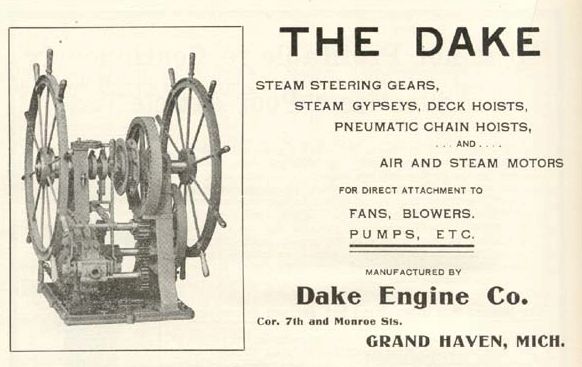

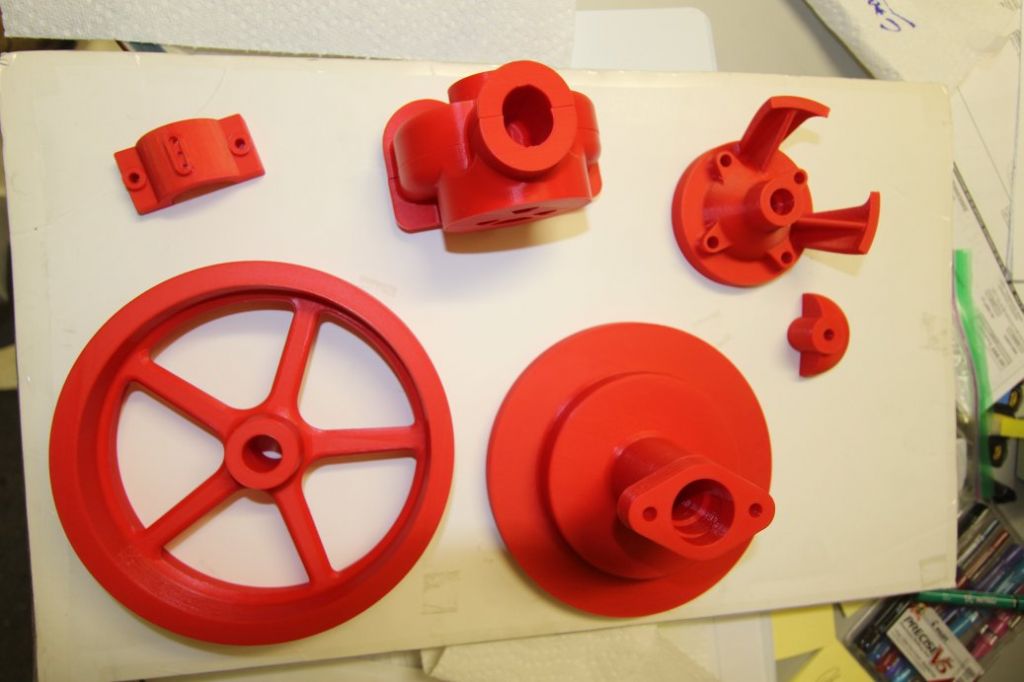

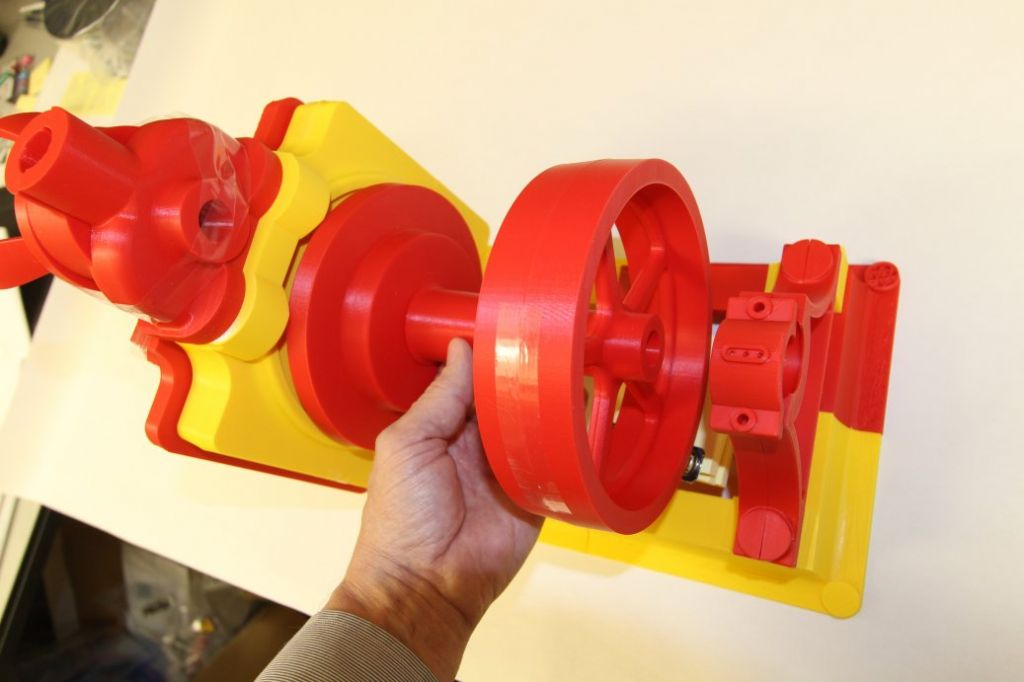

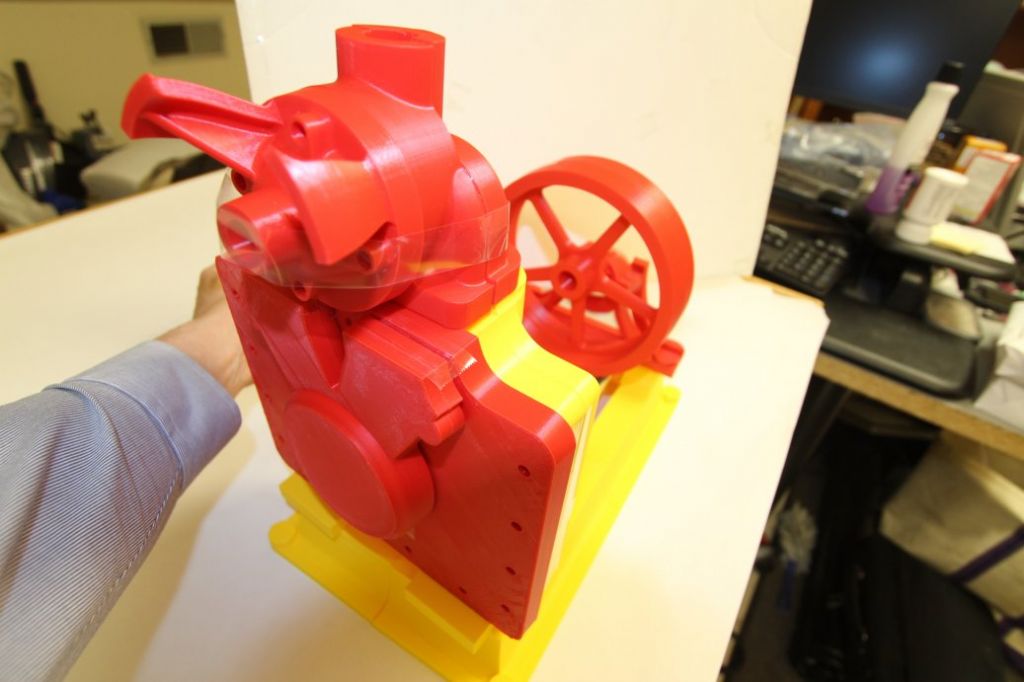

The only way to finish an engine is to start on an engine, and so I have started working on the base pattern for the Dake.

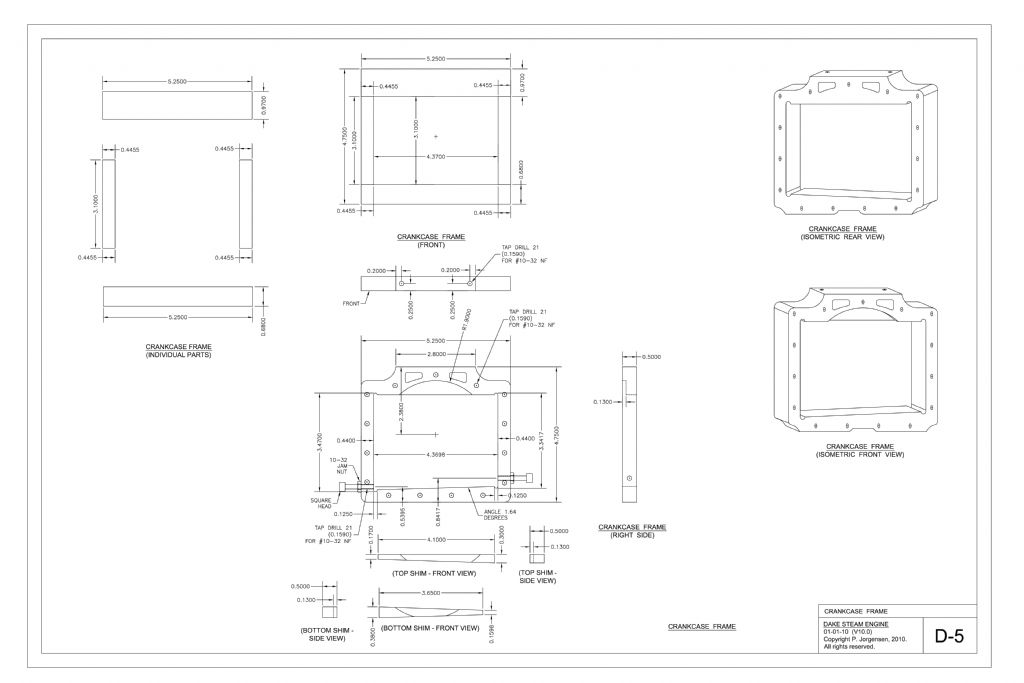

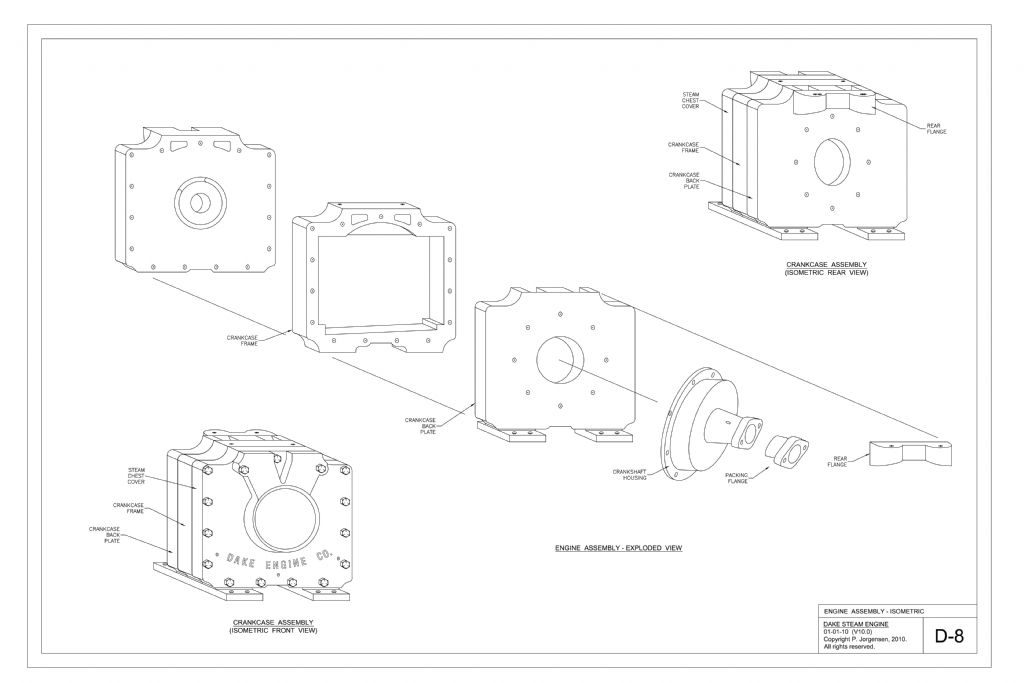

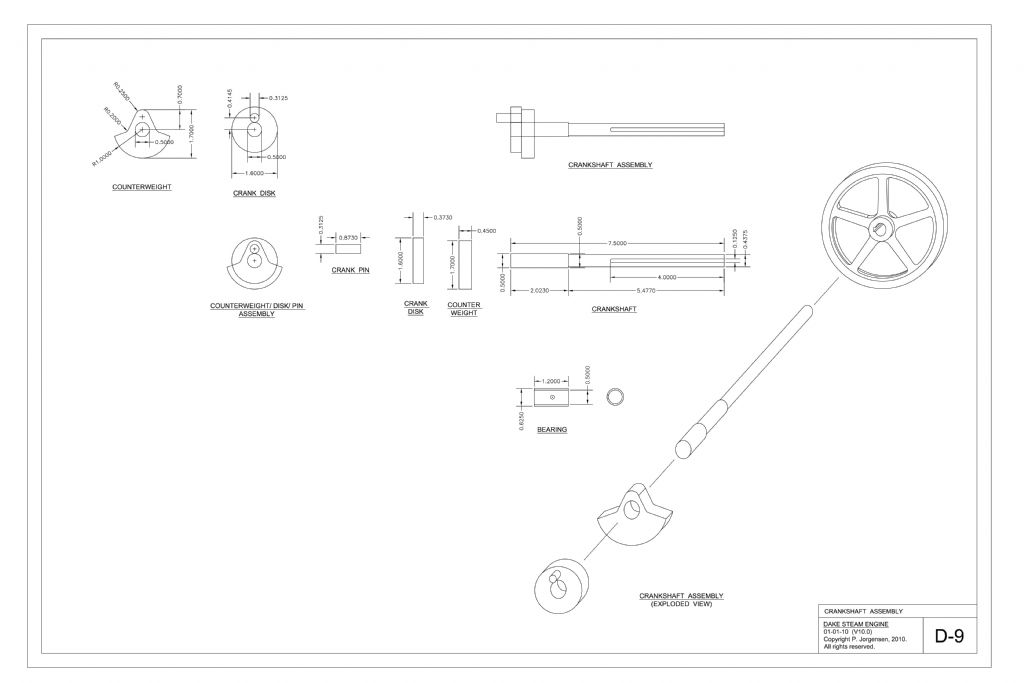

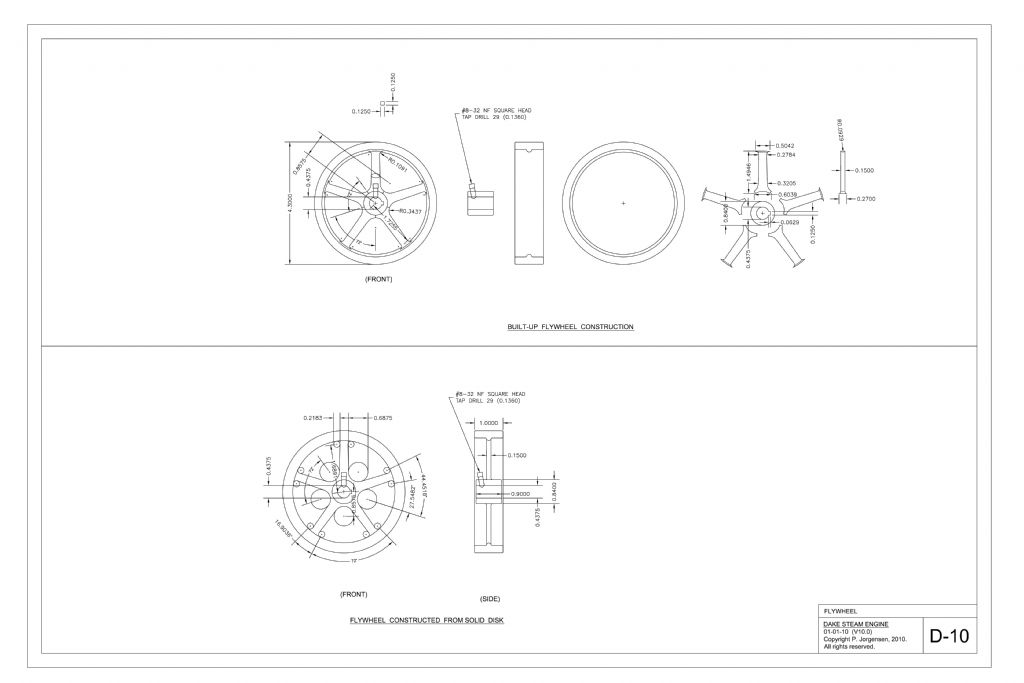

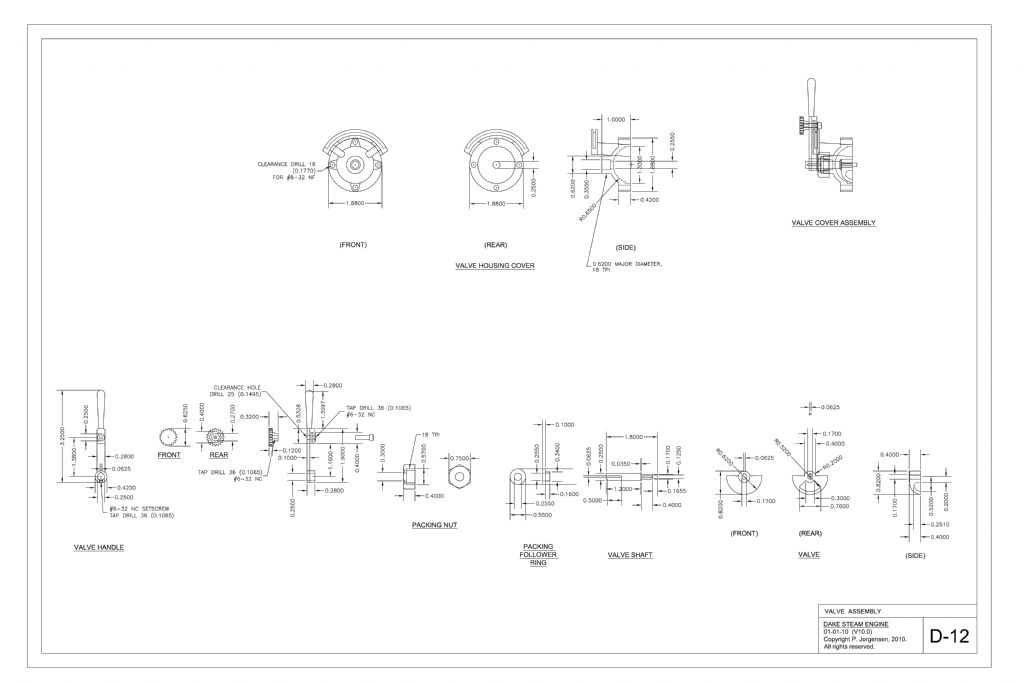

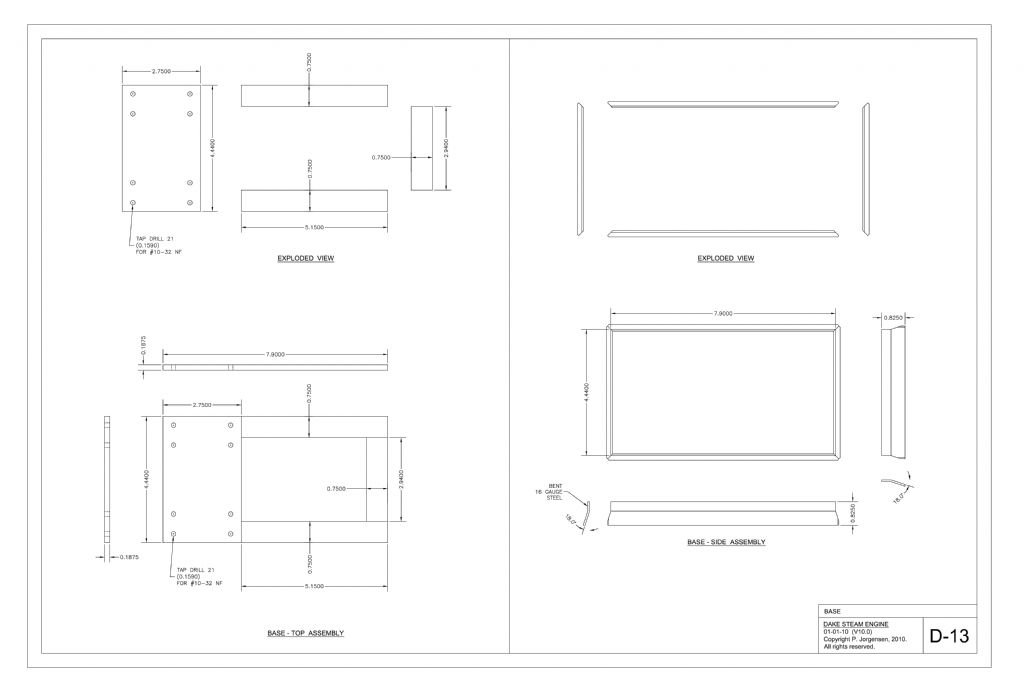

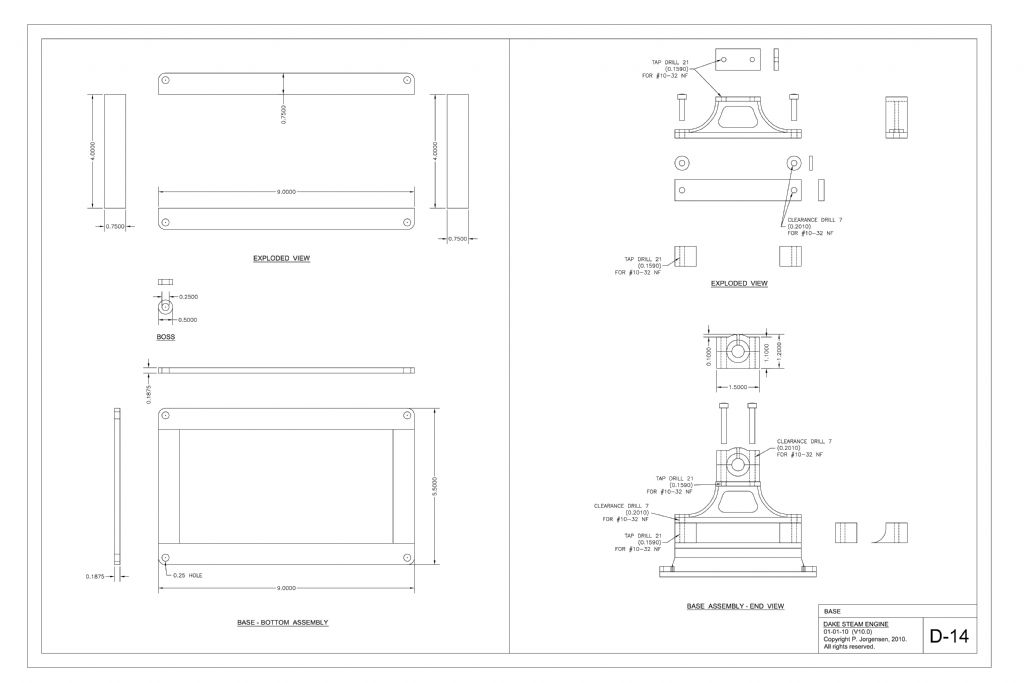

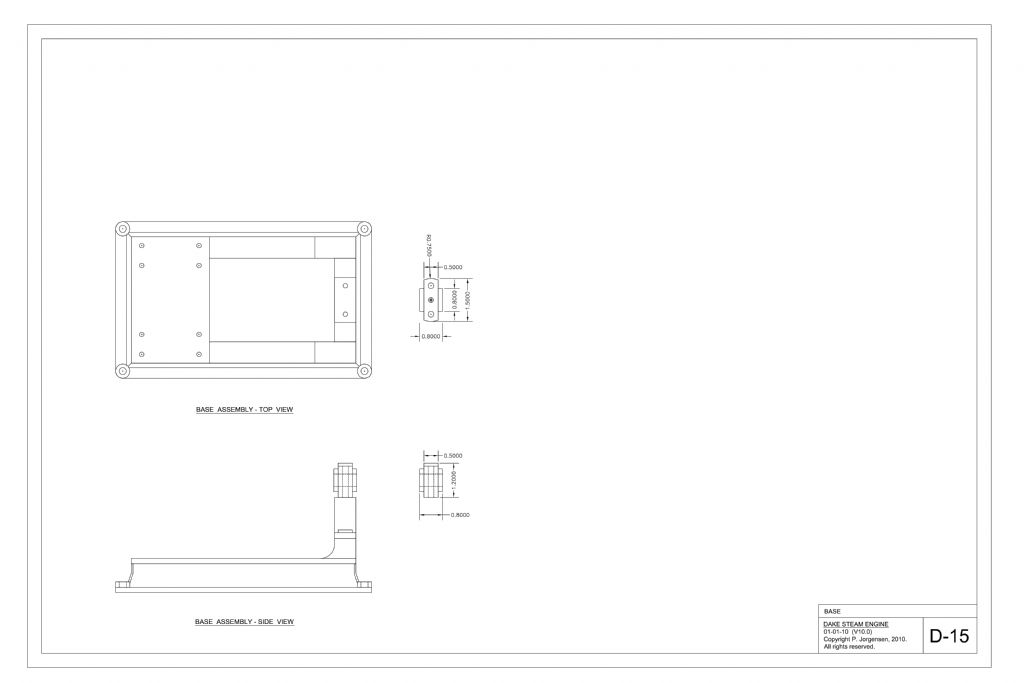

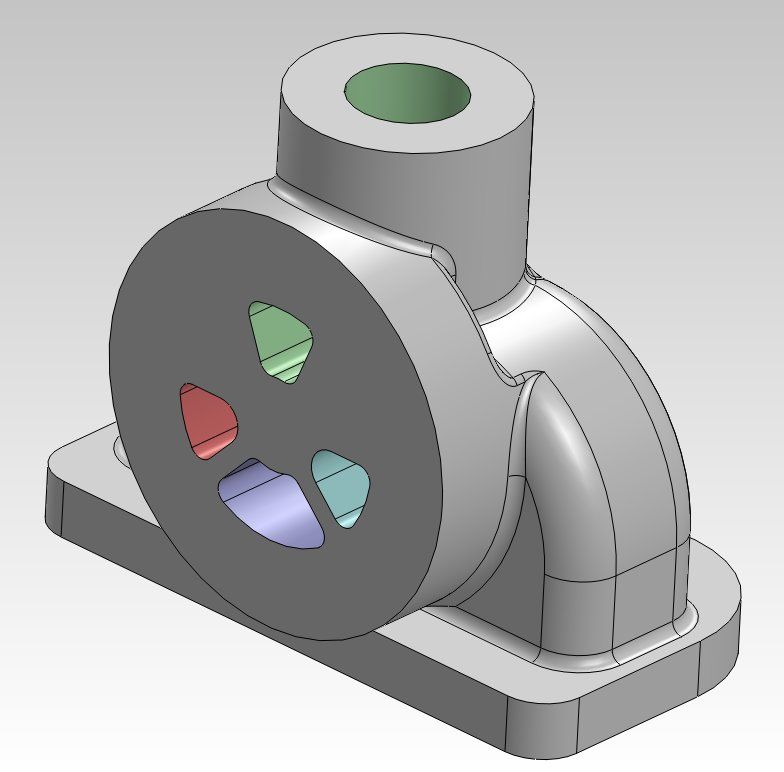

When I created the drawings for my Dake, I was not into backyard casting, and so everything was set up for a barstock build.

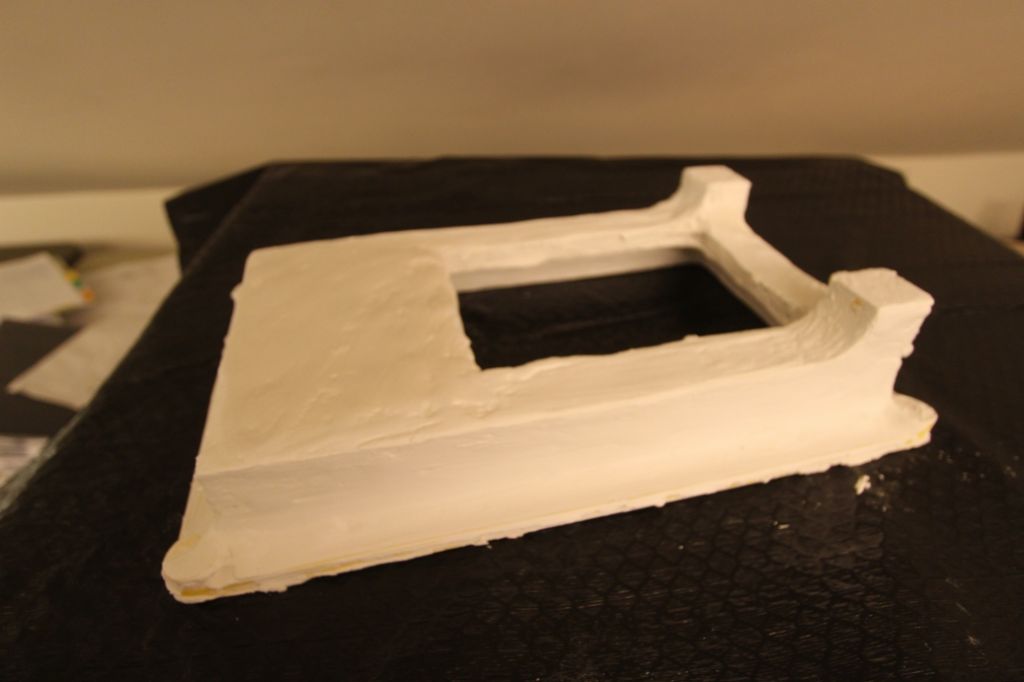

This is coming back to haunt me a bit, and so I am having to fill the base pattern with wall patch compound.

I could go back and reprint the base pattern, but I think at this point I will forge ahead, and just salvage the 3D prints that I have.

As I got into foundry work and pattern making, I realized the importance of things like draft angle, fillets, overhangs, machining allowances, etc.

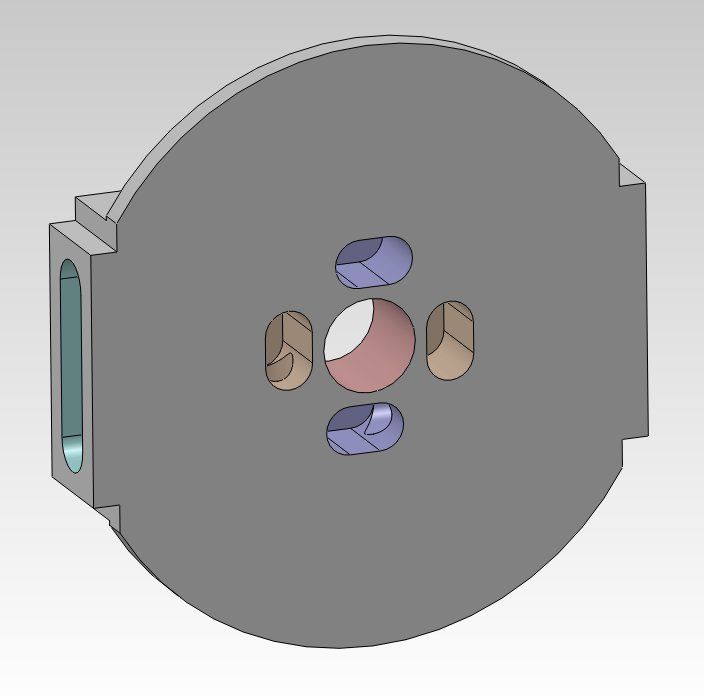

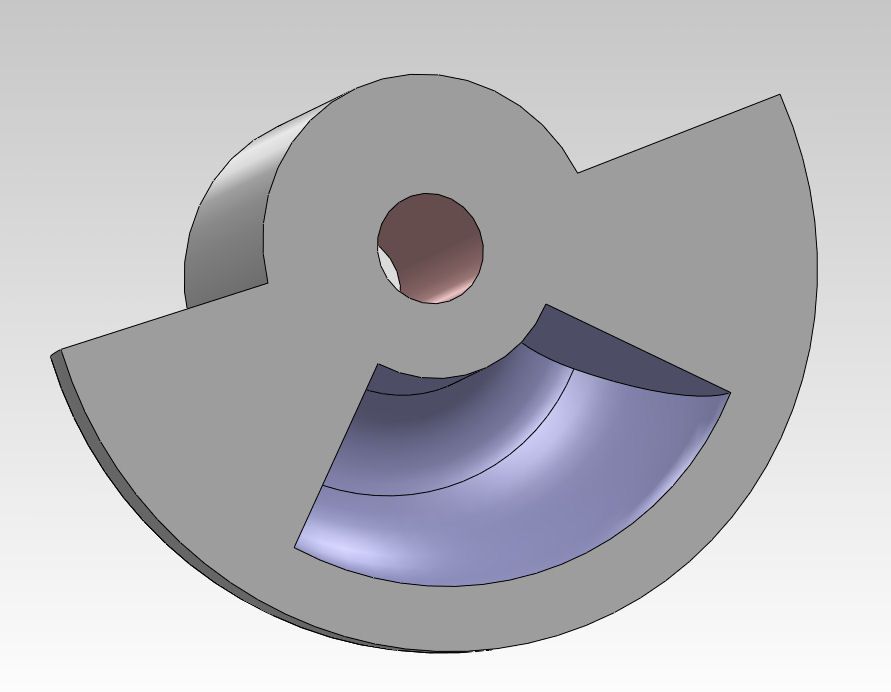

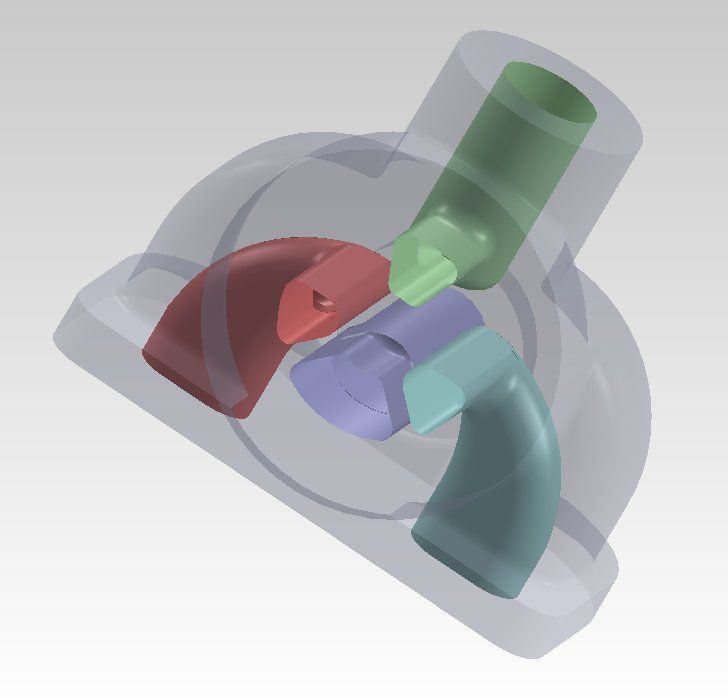

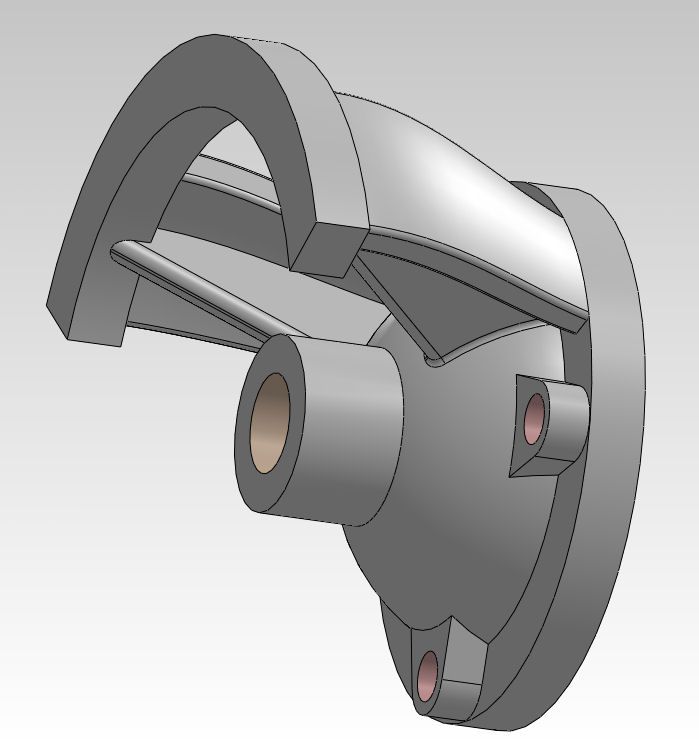

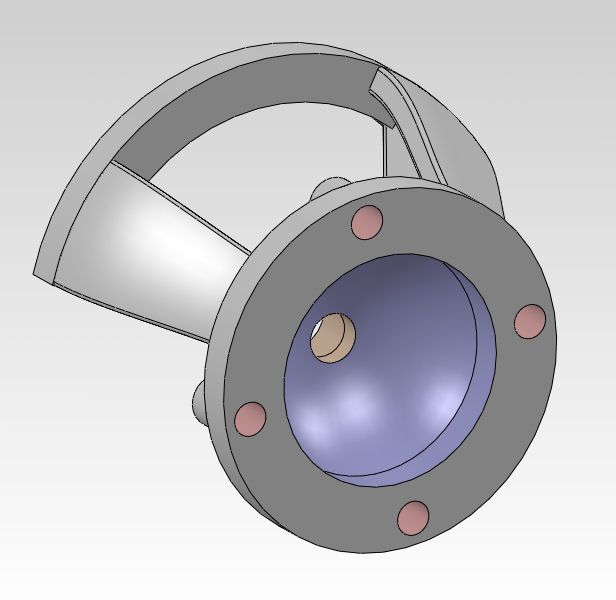

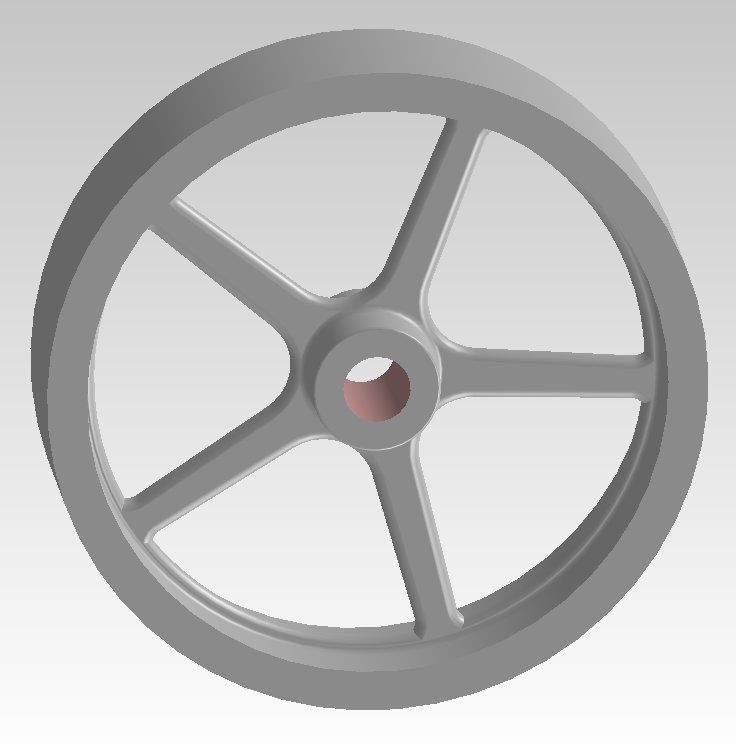

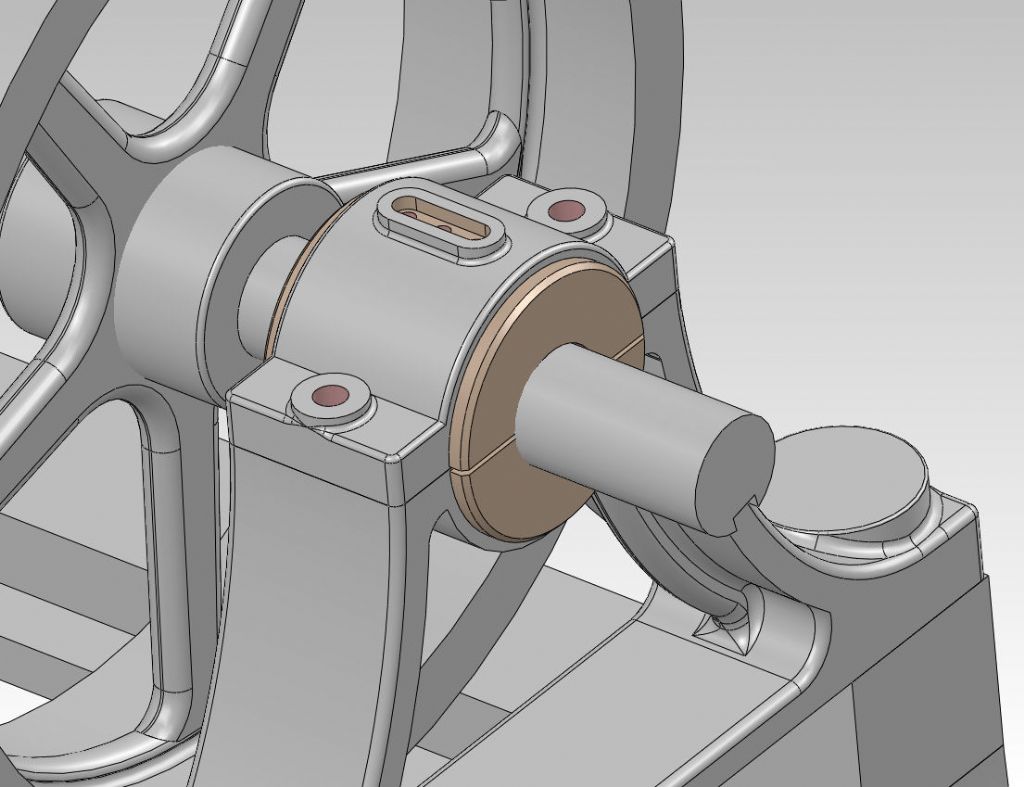

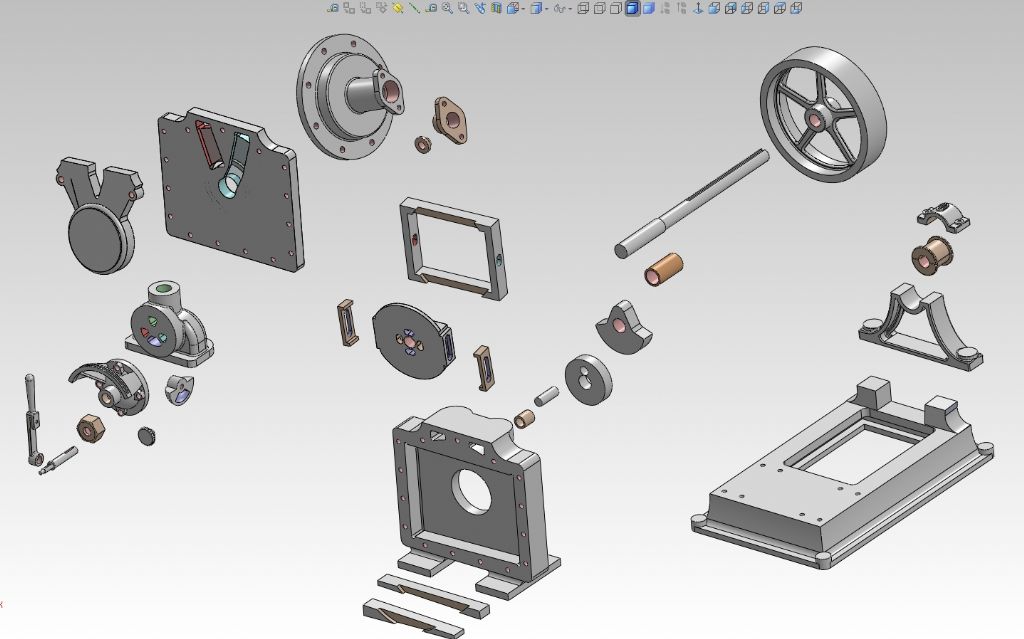

What I do now is complete my 3D engine models without many fillets (perhaps no fillets), and with no machining allowances.

Then I create the 2D drawings, which reflect as-machined dimensions.

Then it is back to the 3D model to add fillets (using too many fillets initially really clutters up the 2D drawings), and add machining allowances. The fillets and machining allowances can be toggled on and off in the 3D program.

And finally, in the 3D slicer program, I add a shrinkage multiplier of about 1.015, just prior to 3D printing the patterns or pattern pieces.

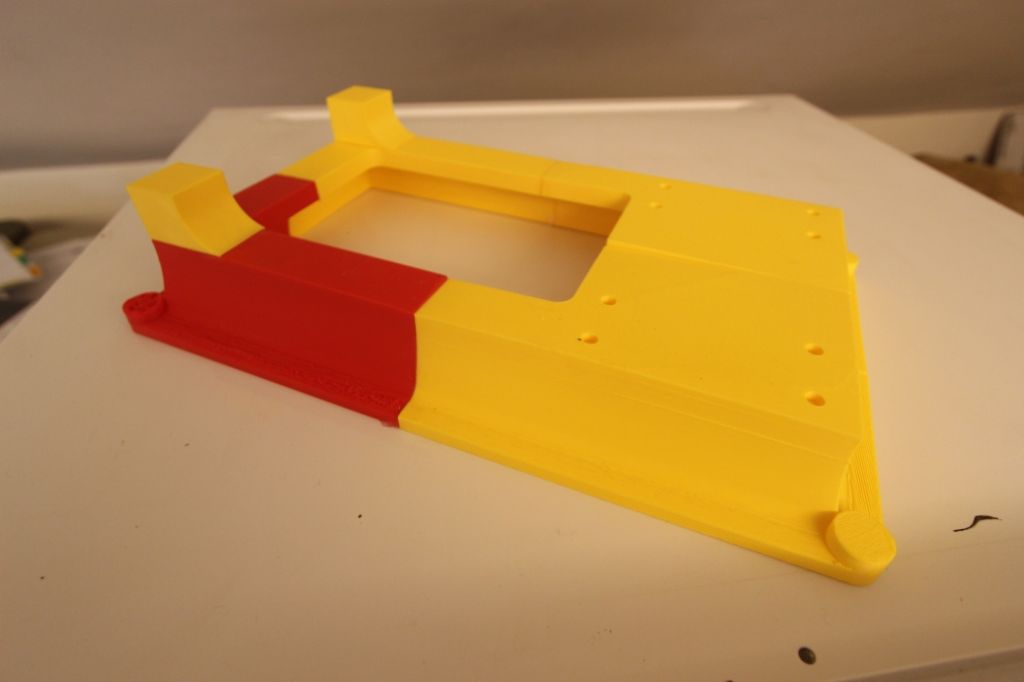

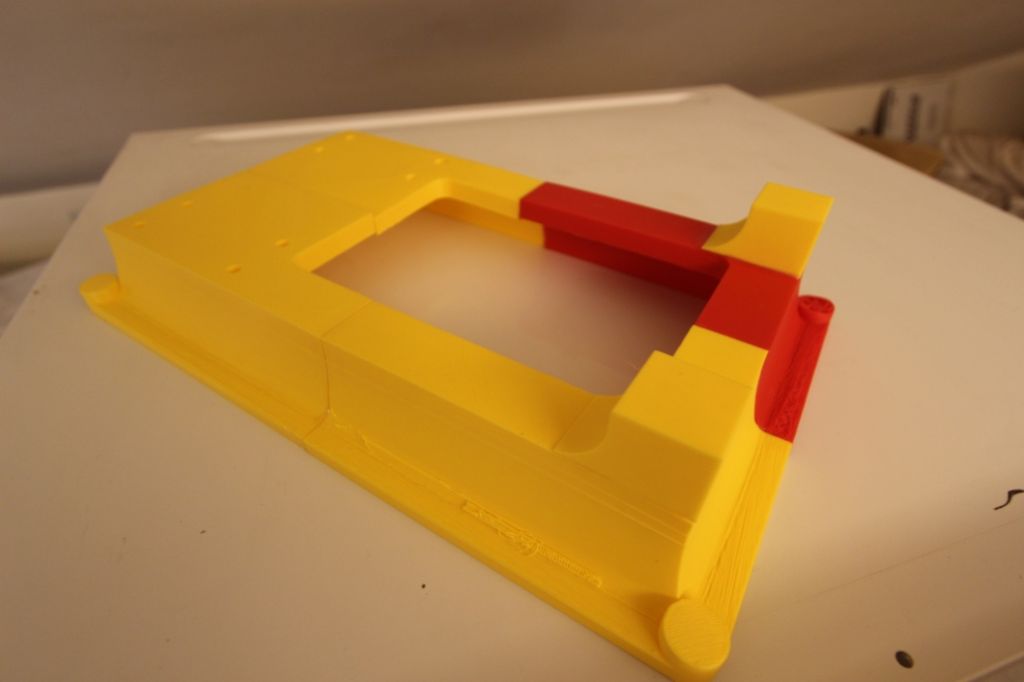

My Prusa is too small to print the entire base pattern, so I printed it in four pieces.

I had some slight bed lifting issues with one piece, and so I epoxied my base pieces together with them all being on a flat surface, and I will work out the warpage issues with filler.

Since this pattern will be fragile, I think I will cast a permanent pattern in 356 aluminum.

The filler is a mix-on-demand powder, used for patching wallboard.

If I had set up my 3D model correctly, and if the 3D printed patterns all been perfect, then I would need very little filler.

Alas this is not a perfect world, and so I am using a rather gloppy approach with the filler.

Most of the filler will get sanded off, and luckily this filler sands relatively easily.

The Durham's wood putty does as advertised, ie: it dries "hard as a rock", and so I don't use Durhams, since trying to sand it ruins the nearby wood or plastic pattern.

Edited By PatJ on 23/07/2022 03:46:33

Edited By PatJ on 23/07/2022 03:51:23

PatJ.

PatJ.

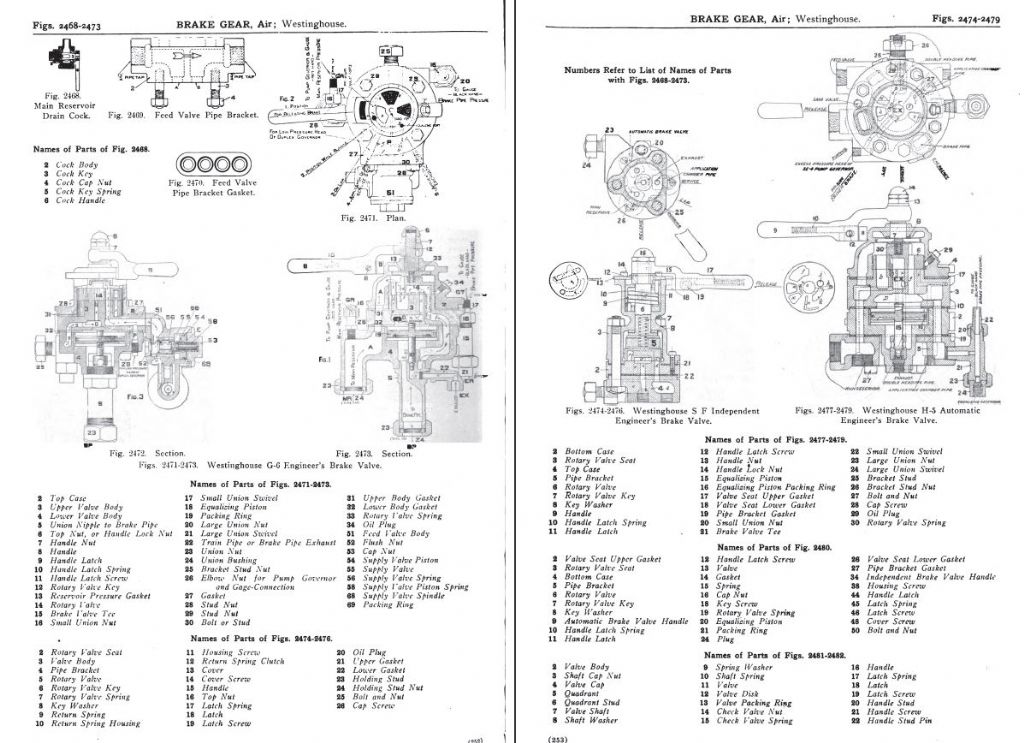

. These days I generally use an 11"x17" format, which is much easier to plot and handle in the shop.

. These days I generally use an 11"x17" format, which is much easier to plot and handle in the shop.