You need to get hold of a copy of 'The Steam Engine of Thomas Newcomen', by Rolt and Allen. Get the Landmark edition of 1997 if possible, it has a better bibliography. This book does mention a wide range of information about this engine.

Gravity was used to give a pressure to the injection water. It was simple and effective. When John Smeaton started to look at the design of the engine around 1770, he said that the injection water system should be as high as possible in the engine house. He also specified that the injection water nozzle should be square. This broke the jet up to provide a better spray. To see how this works, look at the internet site ' physicsgirl smoke rings ', and see the effect of blowing a square smoke ring. Water, being denser than air would be slightly different, it would tend to fly outwards.

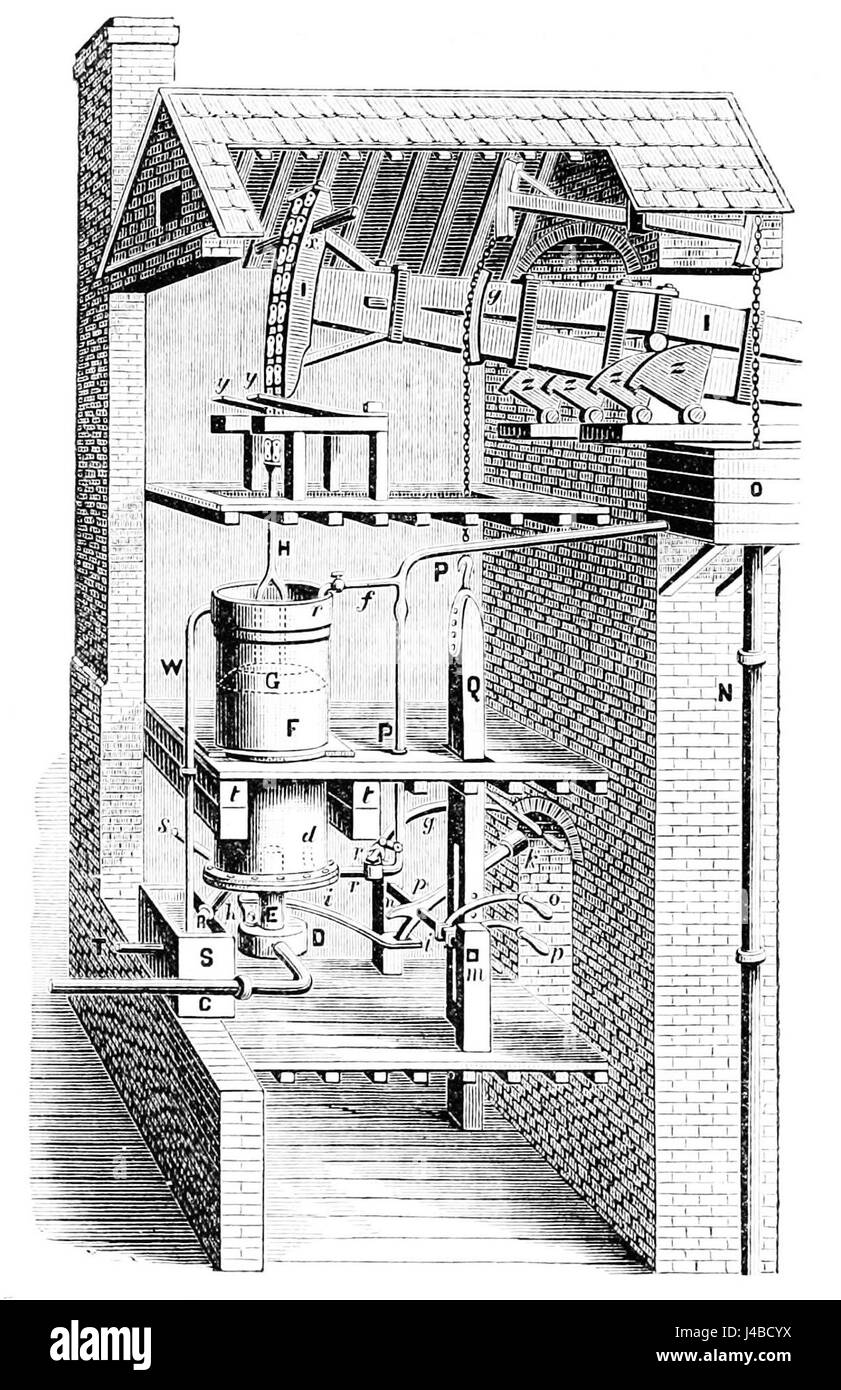

Getting water up into the injection tank was an interesting problem. The Thomas Barney 1719 engraving of the Dudley Castle engine shows a small pump connected to the beam by a heavy connecting rod to pressurise the water sufficiently for it to rise to a level where it could flow into the injection cistern. The jack head pump came a little later ; it was connected on the main pump end of the beam by a light chain. As the main pump was lifted, the jack head piston was also lifted, forcing water up a pipe to the cistern. The John Smeaton engine drawing shows a more complicated arrangement using an auxiliary beam to operate a lift pump by a chain connection.

Model Newcomen engines have different problems, you would probably need a small motor driven pump to supply injection water at three or four psig. The main pump on such an engine works best using a jack head pump with an adjustable valve to control the flow of water from the pump. A friend of mine had a model engine, built by a toolmaker from his scrap box. I first saw it about 1998 or 99 at a Heritage weekend at Elsecar. I walked into a room with this model working away in a corner, started talking to the operator, and over twenty years later we are still talking. His engine was driven by steam from a pressure cooker, ran very effectively, and provided information about these engines that can be found nowhere else. This engine has now worn out, he has another that he built based on the Dartmouth engine. The single lever valve gear has caused problems, so is probably unsuitable for a model. He thinks that model Newcomen engines can work very well, but do need care, starting with the fit of the piston in the cylinder.

The model Newcomen engine that James Watt worked on still exists. It is in the Hunter Museum in Glasgow, an example of a clock maker's or instrument maker's skill. There is a similar model in Kings college at the University of London.

Jim Andrews wrote a paper about the differences between the Newcomen and Watt engines, and gave talks about it. The paper does not appear to have been published.

Over the last three hundred years a huge amount has been written about the Newcomen engine. The Newcomen Society has published nearly ninety papers about it. Over thirty years ago I began to read about it, and when I was deemed too expensive to employ in 1992, I began work on a patented version dating from 1790, the Heslop engine. Twenty years later I had just about worked out who did what and when and read a paper to the Midlands branch of the Newcomen Society when a row broke out about the site of the 1712 Newcomen engine. So, along with some other people I started to look at the evidence. I did come to a conclusion about it that fitted with some of the contemporary writings ( Well, about thirty years after. ) I have continued to collect information about this engine and others. We still have large gaps in our knowledge and understanding of these machines. People talk about the lack of efficiency of these machines, but at the time there was nothing else that could get water out of mines, apart from water wheels and windmills. The problems that they had are still with us in renewable generation of power.

I think that is all for now. The history of this engine sprawls everywhere, and fresh items keep coming to light. In 2020 I found nine separate items from auction sales to paintings, drawings and one article about a well known engine that I did not know existed. Two items allowed me to estimate the size of engines that we know existed, but knew nothing about. If you think that we do not know a lot about English engines, then the Scottish engines hardly exist at all, and European engines are very difficult to find anything about apart from the fact that they existed in some cases.

If anyone has any further questions I would be happy to discuss them.

Regards. Mike Potts.

Michael Gilligan.

Michael Gilligan.