A look at the possibilities offered by 3D scanning with the Creality Scan Ferret.

3D scanning is a technology that digitally captures the three-dimensional geometry of physical objects, converting them into detailed and accurate computerized representations. It employs various methods such as laser-based distance measurement, structured light projection, or photogrammetry to record the spatial dimensions and surface characteristics of an object. By collecting a multitude of data points across the object’s surface, a point cloud is generated ideally forming a highly detailed and precise digital model. This digital representation can then be further processed and refined to create a 3D mesh or solid model, providing a virtual counterpart to the physical object. 3D scanning finds applications in diverse fields, including manufacturing, design, healthcare, cultural heritage preservation, and virtual reality, offering a versatile and efficient means of capturing real-world objects in a digital format for analysis, modification, or reproduction.

Scanners find applications from engineering and architecture to film making and computer game production. In our workshops, this potentially allows us to work with objects that are otherwise difficult to measure or reproduce. In particular, 3D scanning allows us to capture and reproduce ‘organic’ or decorative shapes. There are numerous potential uses, but some of them are:

Enjoy more Model Engineer reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

- Scanning existing objects in order to produce patterns for castings.

- Scanning irregular shapes to allow 3D printing of mating components.

- Rescaling real-world objects (even people) to use with scale models.

- Making unusual or awkward shapes using modelling clay, card or other items to make a mock-up object which can then be scanned and manufactured in a more durable material.

The scanned and edited object can be reproduced. The obvious approach is 3D printing, but in you could cast metal objects from 3D printed patterns or use a CNC milling machine.

The Creality Scan Ferret

The curiously named ‘Scan Ferret’ is a compact scanner aimed at the hobby market, that uses a combination of depth sensing IR and visible light cameras. It can be used in combination with a turntable or in a handheld mode attached to a mobile phone.

The scanner comes in a nicely presented case, together with a handgrip/tripod (which contains a rechargeable battery to power the scanner if used with a mobile phone), a phone clamp, a gimballed mount for the scanner itself and several leads. There is also a USB key with the necessary software, although Creality recommend downloading the latest version.

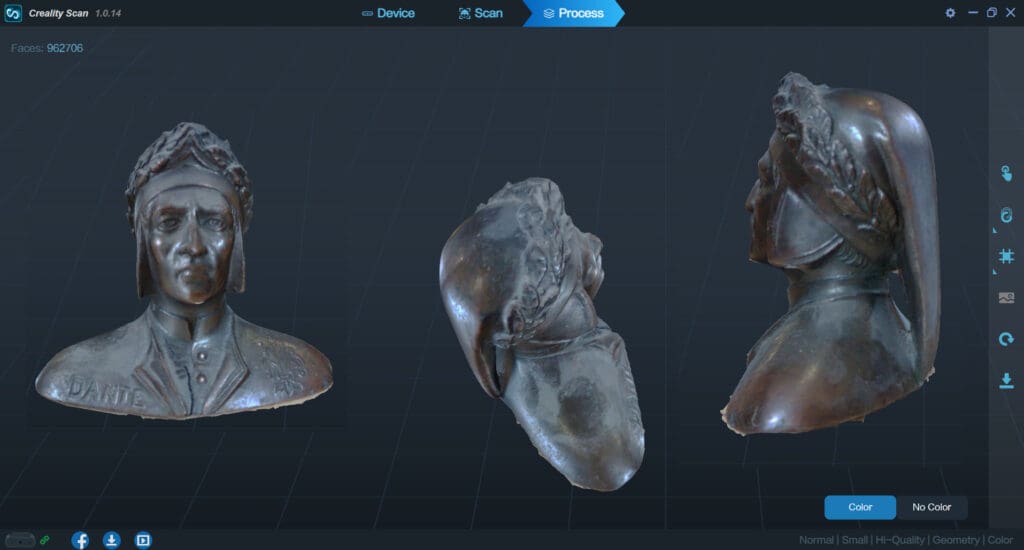

I found that patience and practice are required to get the best results, it’s important to adjust the settings to suit the subject. The scanner can capture a ‘texture map’, alongside the 3D information. This is used to ‘wrap’ the scanned data. The photo shows a composite image with various views of a scan.

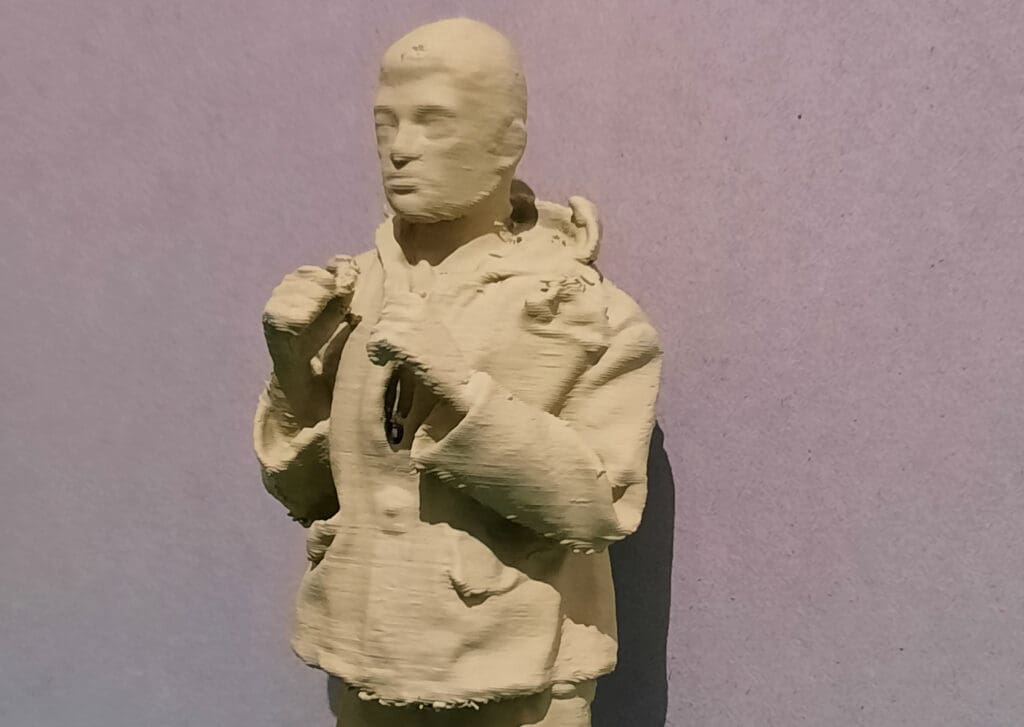

The next image compares the original object with a 3D print of the scan. Dimensionally they are almost identical, but the 3D printed scan is not as crisp in the detail and smooth surfaces are slightly uneven. I think it’s fair to say that the result on this little bust of Dante Alighieri was a success (although I’m not sure what use I have for one, let alone two Dantes…)

For use with a mobile, the phone holder fits between the tripod/grip and the scanner mount and a three-way cable joins power source, mobile and scanner. I was able to load the Android version of the app and it worked with my phone. However, I had problems using the Scan Ferret with my mobile phone. The first issue was that my SD card was short of space, so I had to move a fair bit of data to my computer to free some up. But the real problem was that my phone just wasn’t fast or powerful enough, despite being a fairly recent Samsung Galaxy (my model isn’t on the list of compatible phones). I was able to make captures, but it was tricky, and I generally ran out of capacity before completing a scan. Hopefully my next phone will be powerful enough to use with the scanner.

I had much more success using my PC to capture scans, although I found that the process isn’t always straight forward. The biggest issue was scanning small objects steadily, and the solution was getting a kitchen turntable or ‘lazy susan’. It’s certainly worth watching the Creality tutorials online as well, note that they recommend a manual, not automated, turntable. With an object centred on the turntable, the software guides setting the scanner at an ideal distance. You then start scanning and rotate the object until its image turns green.

If the scanner loses its way you have to backtrack. I also found that it was worth doing a second rotation to fill in any gaps, and to move the scanner by hand to bring any hidden surfaces (such as the top of the model or overhangs) into view. This can be a frustrating process if parts of the object are not clearly visible to the infrared cameras.

My biggest mistake was starting on small objects; the scanner works best on larger objects. Creality demonstrate it scanning a sofa, although it will scan objects down to smaller than your fist. The first serious project I attempted was to try and scan a 1:32 scale crewman for an ASRL, with the intention of printing a double sized version at 1:16. This took many attempts, and the final result was lacking in detail when printed.

I remembered that somewhere in my father’s house were my brother’s old Action Man figures. I managed to find them and dress one appropriately for a ‘turret gunner’. Scaled to fit, I was very happy with the result. The print even has a slightly flattened nose, the result of an accident in the 1970s! The larger figure scanned much better, although I found his shiny black plastic boots would not scan – until I dampened them then coated them with flour! This is something of an issue for engineering subjects as I’ve found steel won’t scan either. In professional scanning it’s not unknown to spray objects with a coating of grey primer or similar.

After 3D resin printing a Brodie helmet for the figure and making a ‘buoyancy jacket’ out of felt I was able to scan a second crewman. The big advantage of such a figure is that you can adapt them to any pose you want. I should mention that the capacity for the Scan Ferret is such that you can scan whole human beings, so the option of getting someone to ‘dress up’ and scanning them is there. My limited experience of larger scans is that they are faster and easier to achieve.

I should draw attention to some of the limitations of this process. The scan of a 3D printed spaceship model shows some of these. The clear canopy was not transparent to IR and scanned as a surface, yet the texture map shows a model figure inside, as if printed on the surface. The loose canopy dislodged during the scan and this shows up as some raggedy glazing bars. The four small ‘cannon’ on the nose did not scan well and some of the lower edges are rather rough. You may also see that part of the surface on which the model was standing has scanned as well. These are not fatal flaws, but would need to be corrected in a ‘post scan edit’ – a skill in need to work on!

Full details of the Scan Ferret can be found at www.creality.com/products/cr-scan-ferret-3d-scanner. I’ve found it a fun and useful device, even if I did get frustrated at times. My overall impression is that 3D scanning has much promise, but that at the moment it is almost as much of an art as a science.