Roger Backhouse returns to Kelham Island to learn about Sheffield’s industrial history.

Kelham Island Industrial Museum was featured for this series in 2005 (Model Engineer, Vol 194 no 4224, 1 April 2005, pp 389-391). It has developed significantly since then, not least by now housing the vast Ken Hawley collection, probably the best collection of tools in these islands, if not the world. Other exhibits reflect Sheffield’s history as a leading tool making centre and the museum emphasises iron, steel, cutlery and engineering with associated social history. It is a fascinating place to visit.

Thanks to a joint York Model Engineers and SMEE visit held in May 2023, I revisited the museum enjoying a guided tour given by Richard Gibbon OBE. He was Keeper of Industrial Conservation, appointed in 1979 to set up exhibits but staying for over ten years!

Enjoy more Model Engineer reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The building was formerly the generating station for Sheffield Tramways (photo 2). A cable tunnel under the River Don linked to the centre of the tramway network at City Square, but this was prone to flooding.

Sheffield’s iron and steel history

Sheffield’s earlier history is well described at the nearby Western Park Museum. The city owed its success to local coal and fast flowing rivers powering water hammers, grinding wheels and blowing engines for furnaces. Grindstones came from the nearby Peak District. Iron was produced locally and turned into steel early on, making Sheffield knives famous, even in Chaucer’s England. Later, Swedish Dannemora iron was found to have better qualities for converting to steel for edge tools, whilst English steel was considered good for making files which became a Sheffield specialty.

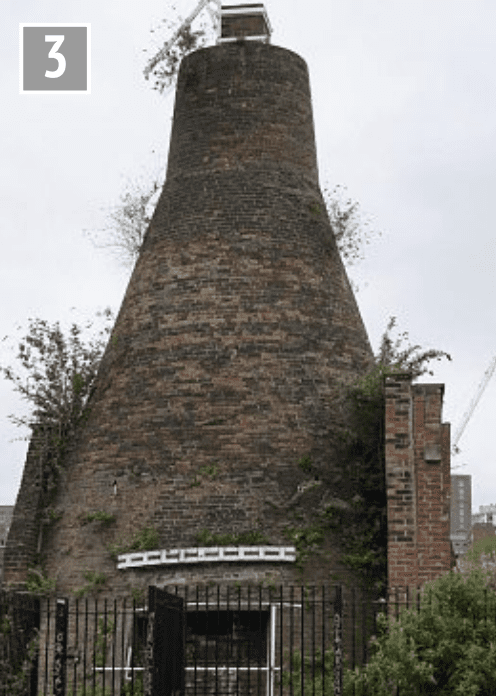

Technical innovation played a part. Iron was converted into steel in cementation furnaces such as this one nearby, looking like an old style pottery kiln (photo 3).

(There is another example of a different design at Derwentcote in County Durham.) Bars of iron were packed into iron chests with layers of charcoal and heated for several days before being allowed to cool. Iron absorbed carbon to become ‘blister’ steel, so called due to its appearance. Unfortunately, though, quality was inconsistent. A Quaker clockmaker, Benjamin Huntsman, tried to make a consistent quality steel for his clock springs. After considerable experimenting he developed crucible steel using specially made clay crucibles. Measured quantities of iron and other ingredients were placed in a crucible and then heated in a furnace. After a three-hour melt the resulting molten steel could be cast.

The museum has examples of former crucible steel furnaces (photo 4). This invention was key to Sheffield’s reputation for quality steel and the crucible process remained in use well into the 20th Century for specialist steels. It was a Sheffield man, Harry Brearley, who invented stainless steel and other alloys have since been developed in the city.

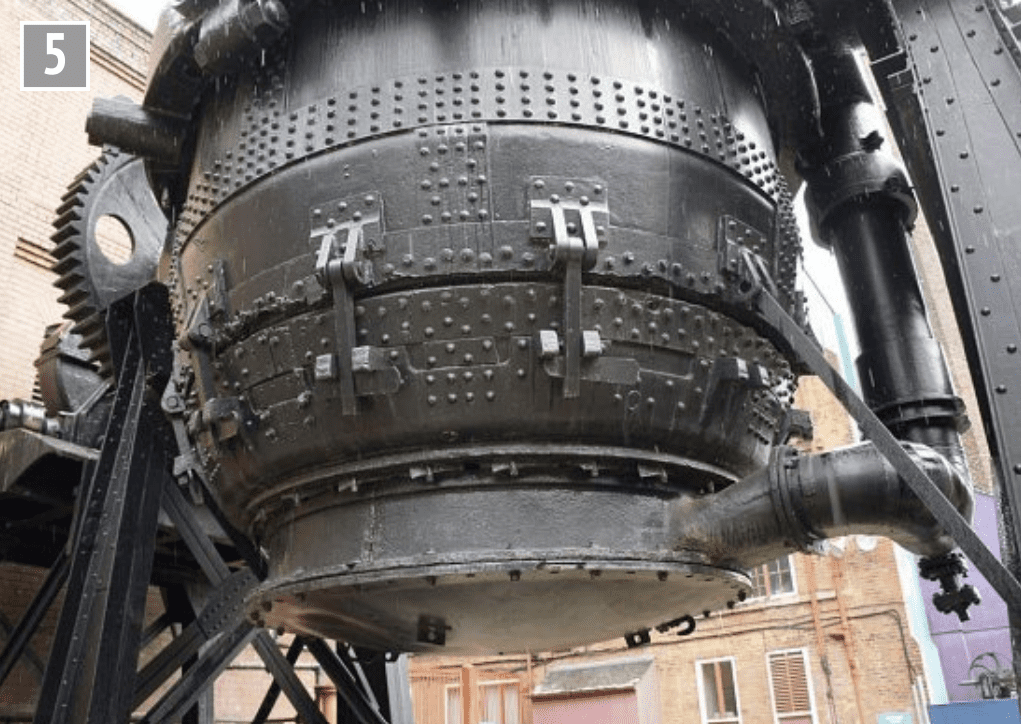

Museum attractions The Bessemer converter, re-erected at the entrance, gives an idea of what is within (photo 5). Henry Bessemer did much of his work in Sheffield and several works had his converters. Air was blown through molten iron in the converter making for one of the most impressive sights in industry! This removed excess carbon leaving mild steel. Mild steel was far cheaper than the crucible steel or wrought iron previously available. It was rapidly adopted for making rails and the first steel rail was made by Robert Mushet using his own process in the Forest of Dean. It was laid at Derby station in 1857. Unlike wrought iron rails, steel did not delaminate in use so lasted far longer.

The museum converter came from Workington and held 30 tons of metal. (There is a much smaller example in the Science Museum in London.) Haematite iron ores found in Cumbria were particularly suitable for steel making using Bessemer’s process.

River Don engine

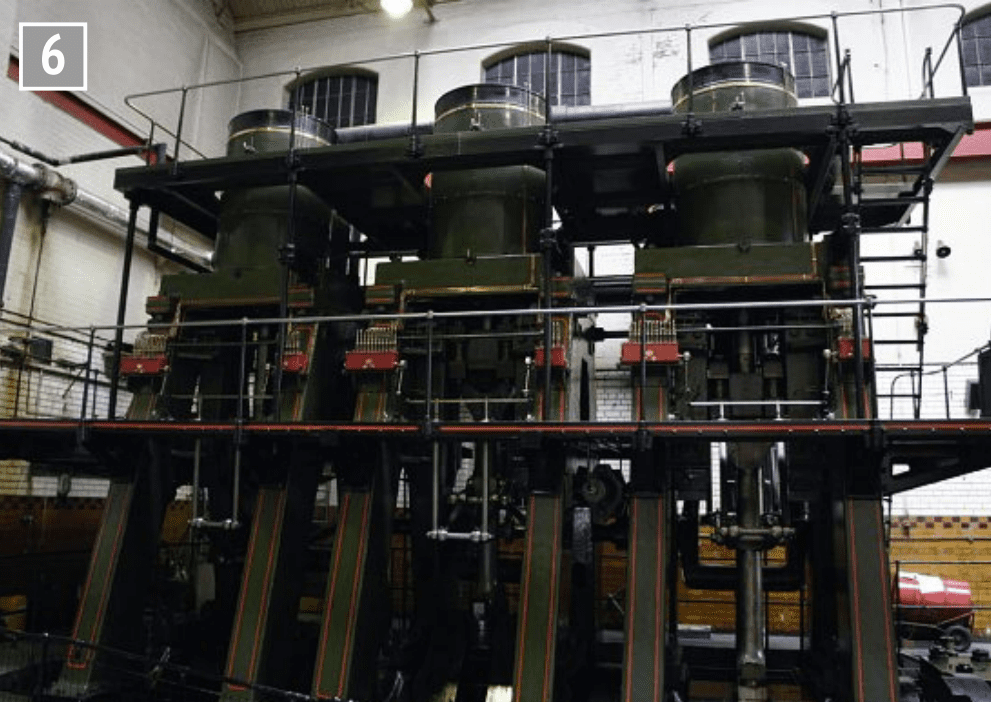

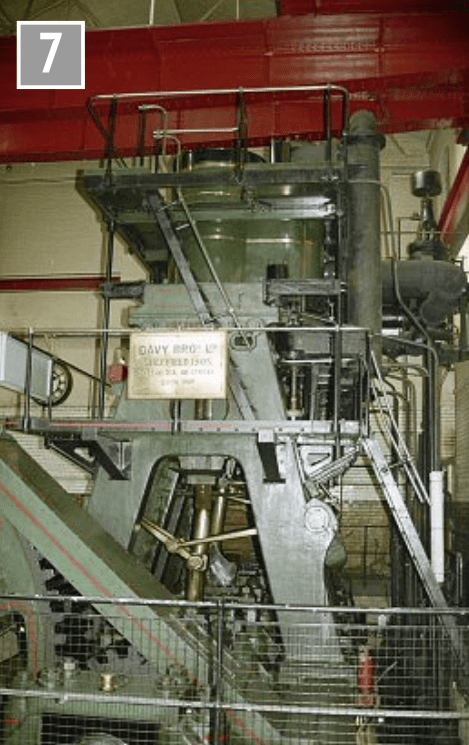

One of the finest exhibits in any British museum, the River Don engine once powered a steel rolling mill (photo 6). Built in 1905 by the firm of Davy Brothers for Charles Cammell’s Grimesthorpe Works it was moved to Vickers’ River Don Works in 1957 and then to the Museum after that closed in 1976. It is usually demonstrated twice a day so the engine can be seen working under steam, and it’s an amazing sight (photo 7)!

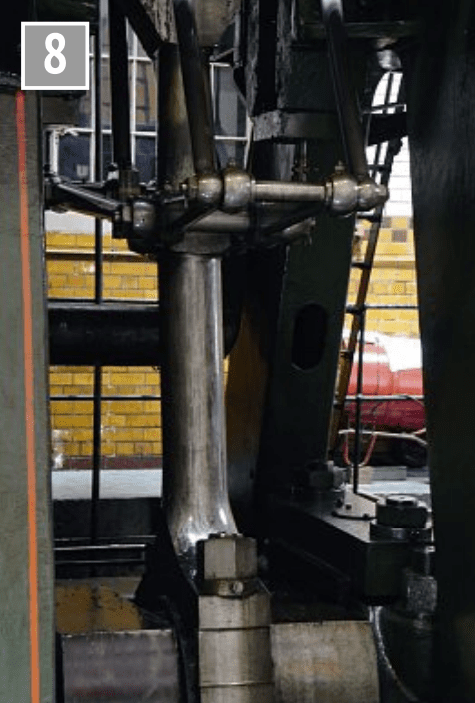

This is a three cylinder, inverted single expansion engine rated at 12,000 horse power and weighing in total over 400 tons. It could roll plate up to 16 inches (40cm) thick and weighing up to 50 tons. Steel rolling must be done quickly or else large slabs have to be reheated. Fast reversal is essential. The River Don engine can be slowed, reversed and brought up to speed again in two seconds without shutting throttles! This is achieved thanks to careful design that focussed on minimising the inertia of the engine (photo 8). The valve gear is derived from Joy but without the slides for a die block. Instead, long arms replicate the action of that block. The engine is rapidly thrown from forward to reverse by a pair of hydraulic cylinders arranged in opposition to each other. Water from an hydraulic main at 300 psi operates the reversing cylinders.

Richard Gibbon says that the base framework, weighing 24 tons, was the worst part to move. He was inspired by an Irishman in his team, Matt Boggan, whose motto was ‘the willing man will find a way’. Matt suggested that a 12 ton crane could move a 24 ton baseplate by careful use of rollers at one end and quantities of old railway sleepers. The job was done – but probably after some anxious moments.

Sadly, it wasn’t possible to preserve the associated rolling mill but a nearby video shows the engine in action rolling steel. It did this from the age of Dreadnought battleships for which it rolled armour plate, to rolling steel for Calder Hall nuclear power station.

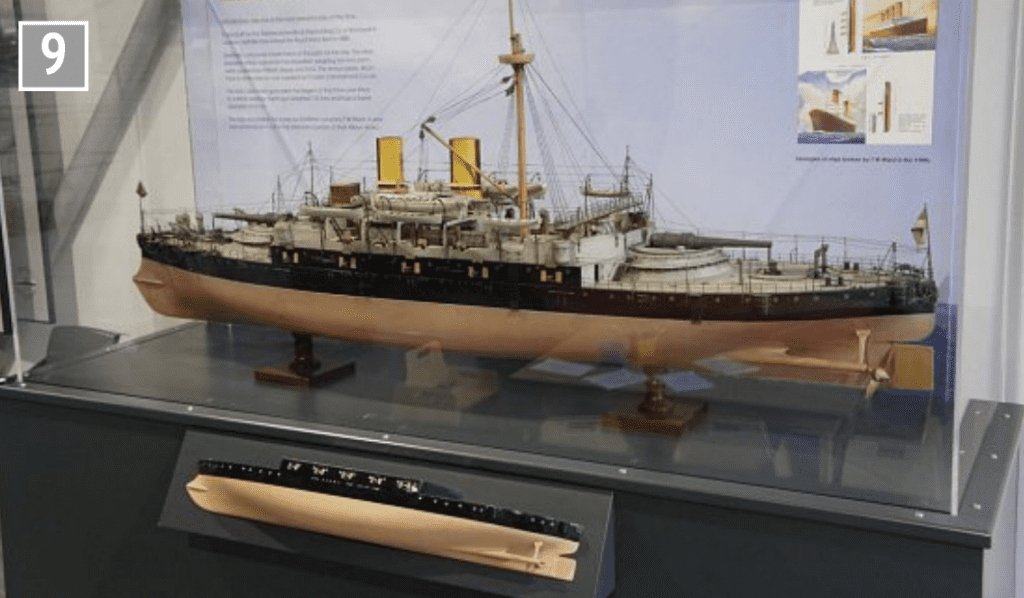

The boiler, formerly used to power the engine from 1980 to 2015, is displayed sectioned nearby, as is a model of the battleship HMS Benbow, a ship built with Sheffield rolled armour plate. This, however, came with a dark side; Sheffield firms set up a cartel, fixing the price of armour plate, leading to enormous profits during the First World War (photo 9).

Outside some smaller rolls show how different profiles and patterns could be produced on bar steel (photo 10).

Crossley gas engine

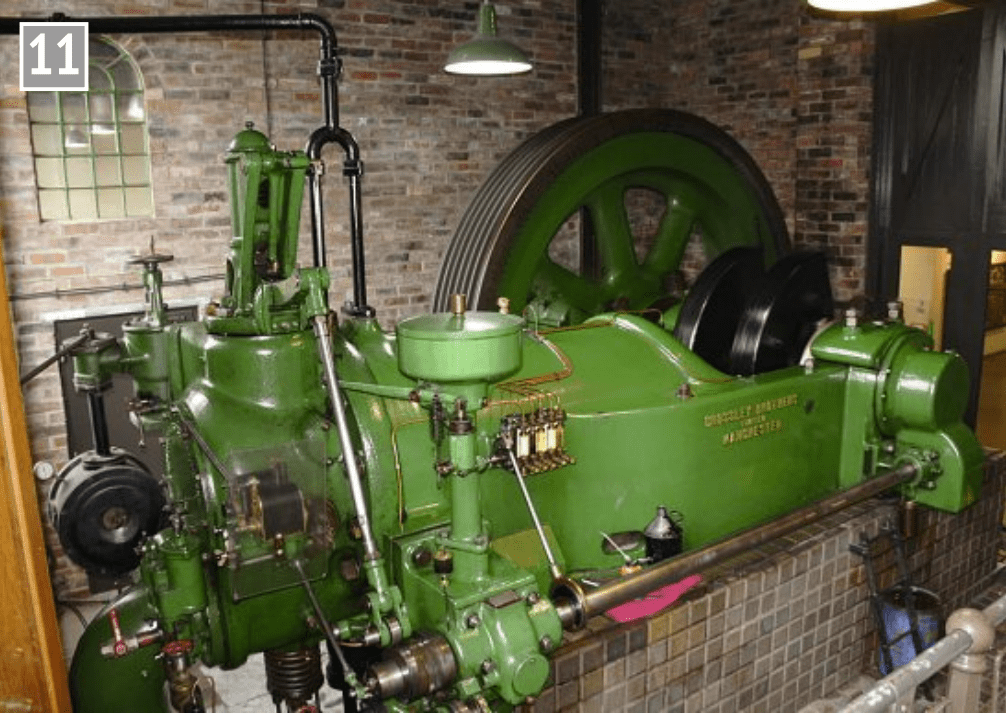

A Crossley gas engine is usually running nearby (photo 11). Invented by Jean Lenoir in 1860, the gas engine was the first working internal combustion engine. Many thousands were built to run on town gas or gas from smaller producer gas plants. Often used instead of small steam units, there was no requirement for a boiler and its associated pressure testing. Sometimes gas engines were used as standby for extant steam plant, as at Darlington’s Tees Cottage Pumping Station. This engine was made in Manchester in 1915 and powered a rolling mill at Hadfield’s steel works. Crossley’s largest single cylinder engine used a four stroke cycle and generated 150 hp at 160 rpm. The museum example can run on propane but is now electric powered for demonstration purposes.

Stephenson valve gear engine

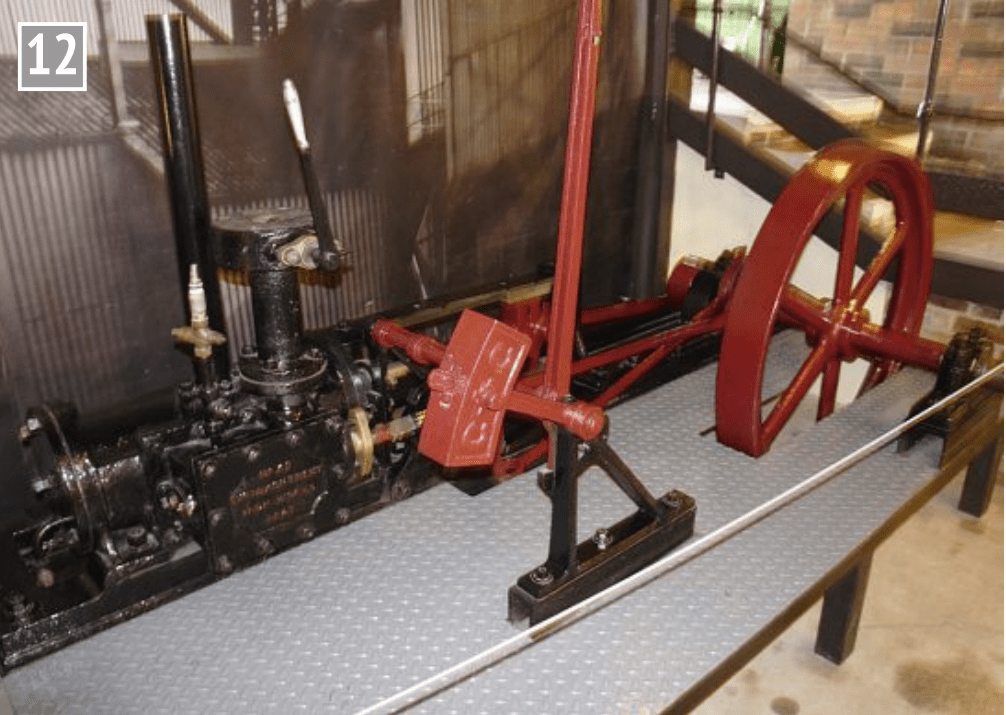

Early valve gears, like the ‘gab’ type used on Stockton and Darlington locomotives, were unsophisticated and did not allow for expansive working so the museum’s pioneer Stephenson valve gear is a highly significant exhibit. The gear was developed by William Howe with, perhaps, a little help from George Stephenson. Here is the engine they developed, demonstrating the first use of Stephenson valve gear used at a colliery in Clay Cross, Derbyshire (where George Stephenson lived and had major business interests). It has forward and reverse eccentrics and a curved link. This could be reversed whilst on the move – gab valve gear could only be altered whilst stationary – and it can be ‘notched up’ to allow for more expansive use of steam contributing to engine economy and efficiency.

Other machines

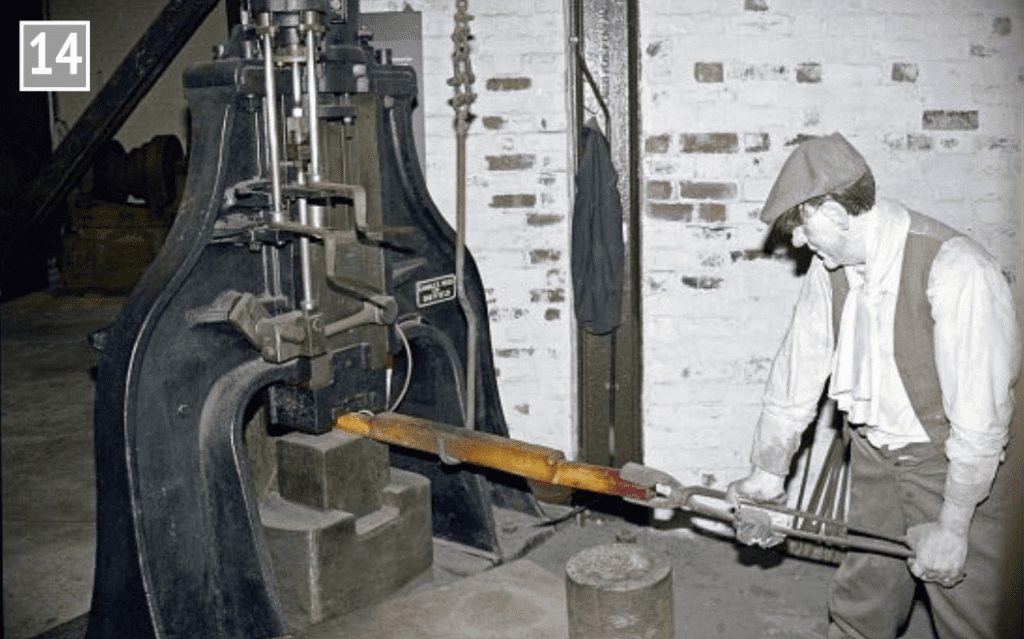

There is a recreated workshop with machine tools (photo 13) and nearby a large lathe. James Nasmyth’s invention of the steam hammer transformed heavy forging in Sheffield as it meant that manufacturers no longer needed to be near a source of water power (photo 14).

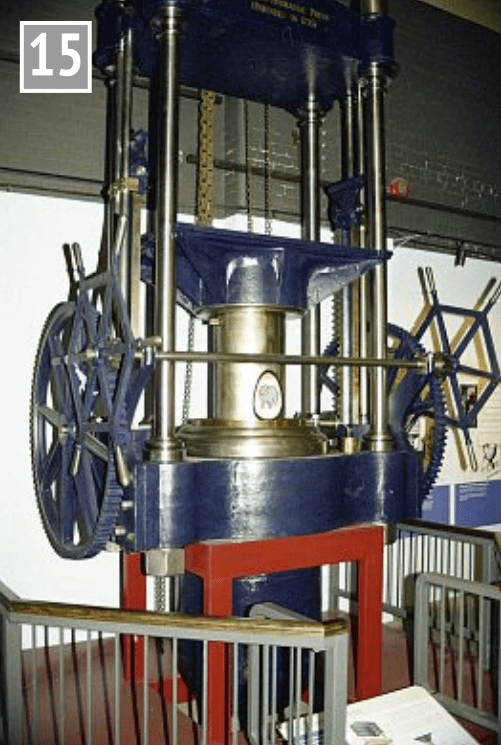

Joseph Bramah was a Barnsley man who trained as a carpenter specialising in cabinet making. He developed an improved water closet, the beer engine and a new type of lock, reckoned for many years to be unpickable. Bramah worked closely with Henry Maudslay to improve machine tools to help make his locks. He was also known for inventing the hydraulic press in 1795 with an example on display (photo 15).

Bailey bridge

Two museum buildings are linked by a steel bridge (photo 16). Donald C. Bailey was a student at the University of Sheffield and designed a portable bridge built from standard units – in essence a ‘kit of parts’- that could be constructed quickly. This was very significant for military applications given that it’s standard practice for an army to destroy bridges behind it as it retreats so ‘portable’ bridges have a high value to the military. Although the design has been replaced by other types, a few examples survive; there is one near Ripon, for example, where many were assembled for practice. The museum has, appropriately, a shorter example of a Bailey Bridge. Many parts were made in the city. To speed construction engineers were trained using kits of one-tenth size parts made by Bassett-Lowke of Northampton. (See Pathe film. https://www.britishpathe. com/asset/78319/ including use of a model.)

Sadly, the Melting Pot play area has closed. In play equipment children could be ‘blown’ from a Bessemer converter down a slide, ‘rolled’ through a rolling mill and ‘hammered’. Equipment was worn out but it’s to be hoped it can be replaced.

Little Mesters workshops

Sheffield was noted for its ‘Little Mesters’ workshops where self-employed specialists would carry out work like making razors, producing pen knives or knife grinding. On my 2005 visit I met Leonard Richardson at the Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet, a ‘Little Mester’ who made surgical instruments. Surgeons sometimes required a special tool and he was the man to make it. The Yorkshire Post (10 June 2023) carried an obituary of Brian Alcock, the last self employed hand grinder. Few such ‘Little Mesters’ still operate.

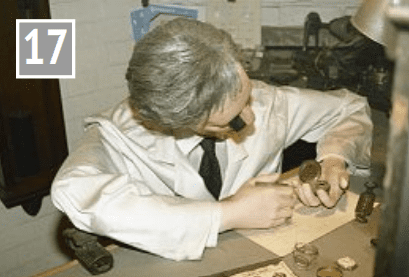

The museum has a recreated street with workshops; one such is the watchmaker’s workshop, a reminder that Sheffield also produced small parts as well as heavy engineering (photo 17). Many readers will have micrometers or dial test indicators made by firms like Moore and Wright.

Specialisms included making magnetic parts and compass needles (photo 18). These skills were put to use when the cavity magnetron was developed during the second world war, essential for centrimetric radar that could be used on ships and in aircraft.

Cutlery and flatware

When open, the city’s Cutlers Hall has displays of Sheffield made products. Besides knives (cutlery) there is also flatware, such as spoons and forks, and larger items. Manufacturers evolved specialist types of knife; one is the so called ‘Nelson knife’ combining knife and fork in one, perhaps intended to be used by a person with one hand (photo 19).

Sheffield Plate was invented in 1743. It had an outer coating of silver rolled on to brass or copper. Far cheaper than real silver it looked ‘just like the real thing’ and the industry grew with nickel-silver adopted as the base material from the 1820s. Sheffield plate was used for bowls, cups, plates and even ornaments. Work pieces could be pressed into moulds so there was a die sinking industry in the city and a die sinkers workshop features in the museum (photos 20 and 21). From around 1845 Sheffield plate was replaced by electroplating but cutlery trades still dominated parts of the city. Museum displays show just how many manufacturers there were, widely dispersed around the city centre.

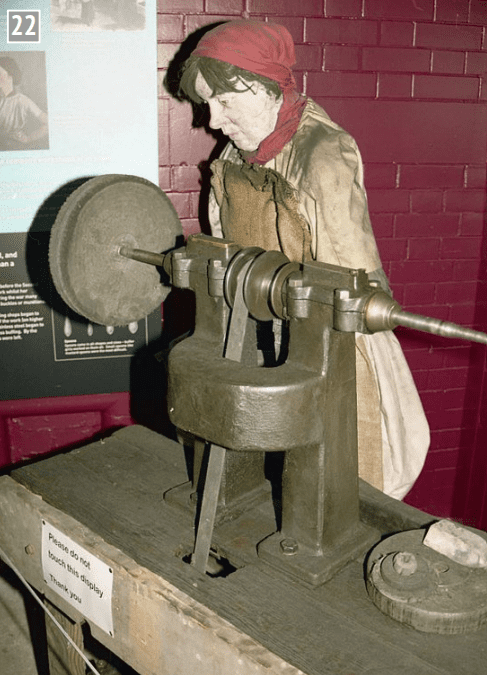

Women carried out many jobs in Sheffield’s industries. One of the specialties typically practised by women was ‘buffing’ to polish cutlery and silver plate (photo 22). Another job was packing for dispatch. Quality cutlery is Use of dies speeded cutlery production helping Sheffield’s firms to dominate the trade. still made in Sheffield and David Mellor makes modern designs nearby at Hathersage where the works are open at weekends.

Words and images by: Roger Backhouse